Context

In this section, we briefly introduce the history and current state-of-play for commercial fishing and ocean research, highlight key work that we build upon, outline motivations for improving sustainability, and describe the guiding frameworks and exemplars for this project. We also note out-of-scope topics.

Contents

- Out of scope

- A brief history of fishing in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Fishing today in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Researching our shared ocean

- Recent relevant government reports

- Why fisheries are important

- We can build on the QMS to improve sustainability

- Guiding frameworks and exemplars

- References and footnotes

Out of scope

As outlined in our Terms of Reference, the report does not review or make recommendations on the areas outlined below. However, the report signposts how these factors impact and interact with the in-scope aspects of the project. Linkages and overlaps between in- and out-of-scope factors will be highlighted. We acknowledge that we are looking at only one part of a complex system, which limits the impact of the recommendations if carried out in isolation.

While there are a select number of freshwater species that are managed under the fisheries management system, we have focused on the marine environment.

Quota ownership and Crown obligations

This project does not make recommendations on distribution, controls of ownership of New Zealand quota, preferential allocation rights, aggregation limits or other factors of quota ownership and Crown obligations.

Aquaculture

Aquaculture and wild fisheries are complementary sectors, each with different solutions for sustainable and ethical seafood production. New technologies and approaches in aquaculture, like the move towards open-ocean farming, may become more important in the future.[1] While these linkages are touched on, they are not a focus of the project.

We acknowledge that we are looking at only one part of a complex system, which limits the impact of the recommendations if carried out in isolation.

Recreational fishing including catch reporting

Recreational fishing is a popular activity in Aotearoa New Zealand with an estimated 700,000 people going fishing in a given year. An estimated 7 million individual finfish and 3.9 million individuals of other marine species were caught by recreational fishers in 2017-2018.[2] Recreational fishing is significant economically, with one report estimating that recreational fishers spend approximately $1 billion a year.[3]

The New Zealand Marine Research Foundation estimates that 6% of all landed catch is taken by recreational fishers.[4] However, the recreational take is more significant for certain species, such as snapper/tāmure,[5] the largest recreational fishery, with recreational fishers responsible for over 40% of total catch across Aotearoa New Zealand.[6] In some areas, the recreational catch exceeds the commercial catch – for example, in Tīkapa Moana the Hauraki Gulf, recreational catches of snapper, kahawai[7] and kingfish/haku[8] exceed commercial takes.[9]

Recreational fishing is restricted by rules (such as daily catch limits and size limits) depending on area and species. In Aotearoa New Zealand, recreational fishing includes both amateur fishers and charter fishing vessels. While the per person catch limits apply to each passenger on a charter vessel, the number of passengers can be such that the vessel’s take could exceed the catch of a smaller commercial vessel (as has been anecdotally reported). While recreational fishing is a contributor to overall catch volumes, it is not a focus of this project. We note that improving our estimates of recreational catch and incidental fishing mortality will be essential for enhancing the sustainability of our fisheries, as well as confronting the challenge of shared fisheries.

Customary fishing (non-commercial)

Customary fisheries are a right of tangata whenua. They include traditional and customary practices and customary non-commercial food gathering. Customary fishing takes place in rohe moana (defined customary fishing areas). Customary fishing rights are guaranteed under the Treaty of Waitangi – and protected by the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992 and 1992 Deed of Settlement.

Customary fisheries are significant although volumes of catch are not readily available. Over 200 kaitiaki have been appointed by tangata whenua to manage customary food gathering, and there are over 40 mātaitai reserves and 10 taiāpure (where tangata whenua can undertake management of fisheries resources). As with recreational fishing, customary fishing is another fisheries activity that sits outside the QMS and commercial fisheries. While recommendations in relation to customary fishing are out of scope, customary practices and knowledge are discussed.

A brief history of fishing in Aotearoa New Zealand

Fishing has always been an integral part of our island nation’s identity. Our fishing history dates back to when Māori arrived in their waka, equipped with advanced fishing methods and knowledge of te moana. Over centuries, Māori extended this deep knowledge to local fishing grounds and their taonga species.[10, 11] As kaitiaki, Māori managed Aotearoa New Zealand’s fisheries under the authority of a rangatira, who was responsible for the sustainability of these resources.[12, 13] The importance of kaimoana to Māori is reflected in the names of people and places, as well as in oral history and legends.[14]

Our fishing history dates back to when Māori arrived in their waka, equipped with advanced fishing methods and knowledge of te moana.

The arrival of Europeans added scale to fishing pursuits, along with new methods and technologies. By the early 1980s, the way we fished had transformed.[15] Fishing was generally limited through licences (e.g. number of vessels), other controls such as gear restrictions, and some limits on access to particular species in particular areas.[16] New fisheries were developed in deeper waters, and our focus shifted to exports. Inshore fish stocks were depleted and the sustainability of fishing practices and management (or lack thereof) came to the fore.[17]

Enter Aotearoa New Zealand’s QMS, introduced in 1986 for an initial 26 species. An innovative initiative at the time,[18] the QMS created perpetual and tradeable private rights in the commercial fish harvest (individual transferrable quota (ITQ)) and aimed to provide for utilisation of the fisheries resource while ensuring sustainability, as well as improving the economics of the industry. Under the QMS, the regulator (now Fisheries New Zealand (FNZ)) sets a total allowable catch (TAC), makes allowances for the customary and recreational sectors, and allocates a catch allowance to the commercial sector (allocated among quota owners through the mechanism of ITQ).

Pā kahawai (trolling lure), Aotearoa New Zealand 1750-1850. Oldman Collection, gift of the New Zealand Government 1992. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

In the years following the introduction of the QMS, some stocks increased[19] although some others declined, but overall, the QMS was acknowledged to be a big step forward as stocks were generally maintained, and the system was recognised and imitated internationally.[20, 21] The introduction of the Fisheries Act in 1996 occurred as a part of wider resource management law reform and further defined the use of sustainability in fisheries management.

Meanwhile, Māori fishing rights (both commercial and customary) had been severely eroded since 1840. The Treaty of Waitangi recognises the rights of Māori to their natural and cultural resources, including fisheries. But these rights were not realised until the Māori fisheries settlement was implemented under the Māori Fisheries Act 1989 and the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992. The settlement acknowledged the forced accommodation between the Treaty and the QMS by mutual consent between Māori and the Crown.

Since the settlement, the Māori seafood sector has experienced significant growth.[22] Iwi and Māori businesses comprise a significant proportion of the commercial fisheries and aquaculture sector, owning 27% of quota.[23, 24]

Fishing today in Aotearoa New Zealand

Today, our marine economy is estimated to directly contribute $3.8 billion to the economy, with fisheries and aquaculture contributing around $1 billion of that figure.[11] Seafood is in demand both here in Aotearoa New Zealand and overseas, and this demand is expected to grow.[25]

Unlike most food production, fisheries involve harvesting in the wild. Seafood, as with other food production, comes with an environmental cost. To grow the fishing industry within a managed quota of developed fisheries, it should be in everyone’s interest to improve the quality, value and sustainability of fish caught – while still enabling an affordable domestic market. An increasingly eco-conscious global market – especially at the premium end – is yet another driver to fish sustainably.

It should be in everyone’s interest to improve the quality, value and sustainability of fish caught.

![]()

Our fisheries management is led by government agency Fisheries New Zealand, part of the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI). We continue to use the QMS within the Fisheries Act 1996 as part of a fisheries management programme that draws on an increasingly broad evidence base to inform management. A significant amount of the fisheries research and data collection undertaken is cost recovered from quota owners.

A report in 2017 by The Nature Conservancy found that Aotearoa New Zealand’s QMS has consistently ranked well against a range of indicators. However, the report noted that we do not routinely report on the ecosystem impacts of fishing, and there are many stocks we know little about.

We continue to learn about the health of our marine environment, the ecosystems within it, and the impacts of commercial fishing. This growing body of knowledge could be a driving force for adapting the way we manage fisheries to ensure their sustainability. But in practice, capturing this information can be expensive and challenging. It is thus a body of knowledge that remains incomplete, meaning many decisions are inevitably made without a comprehensive evidence base, or decisions are not made at all. Combined with the many diverse and strongly held views, this creates an environment in which fisheries management approaches are highly contested, both globally and in Aotearoa New Zealand.[26–31]

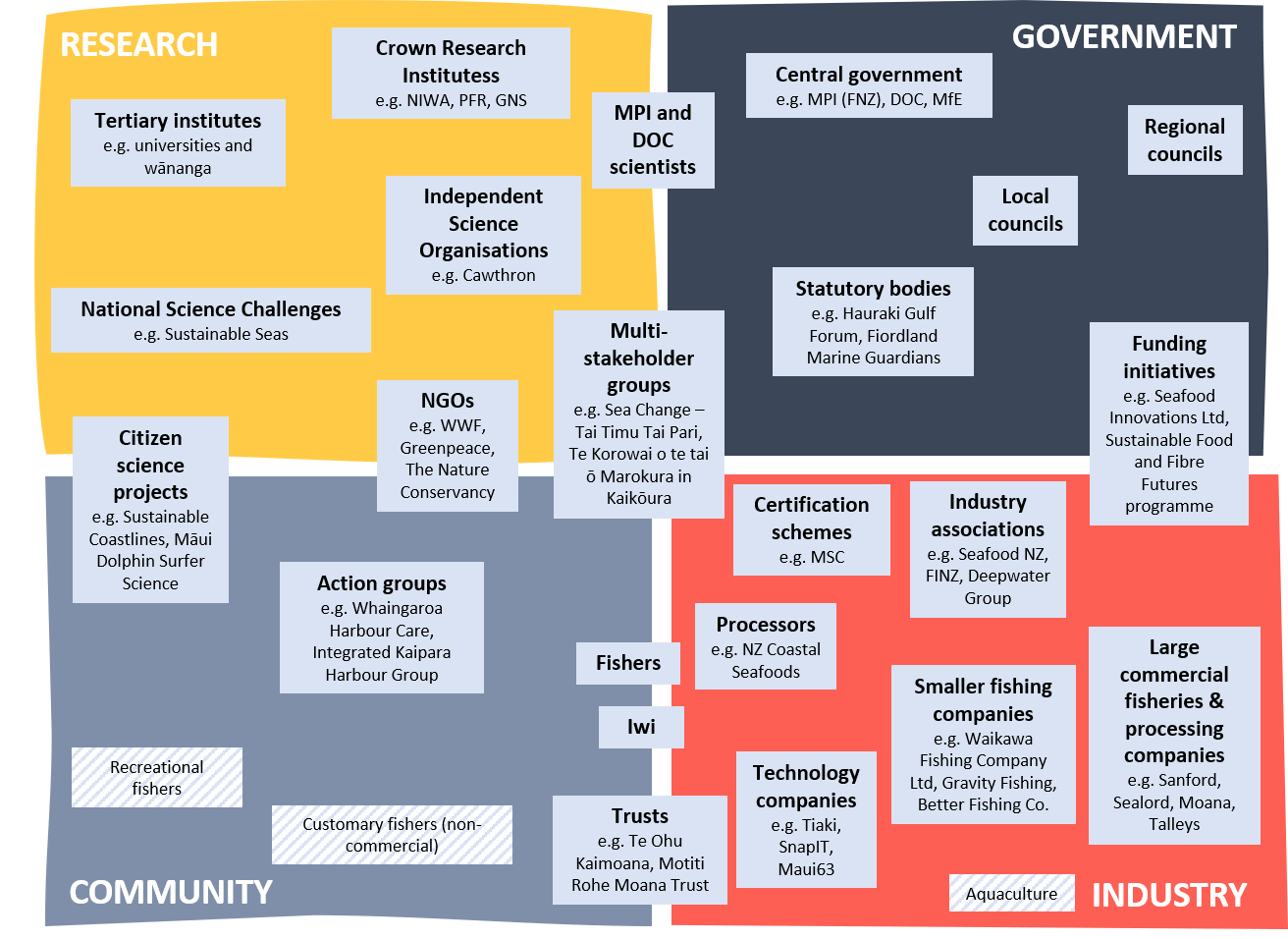

Click image to enlarge. Some of the many stakeholders with interests in Aotearoa New Zealand fisheries.

As well as the range of stakeholders within the commercial fishing industry, many others have an interest in the health of our shared marine environment. This includes the recreational and customary fishers, the general public, researchers, government representatives, tourism operators, those interested in mining the seabed, environmental groups, iwi, community groups and future generations.

Tensions between commercial and environmental priorities often surface, but new multi-stakeholder approaches show that, with a shared vision and goal, people can come together to address complex issues in our marine environment. Currently, these are relatively few and covering small areas, but they provide inspiration for a way forward.

There is a significant opportunity for innovative technology, new scientific approaches, and more extensive data collection and use, to better inform our fisheries management as we strive for more sustainable practices. This report examines these in detail.

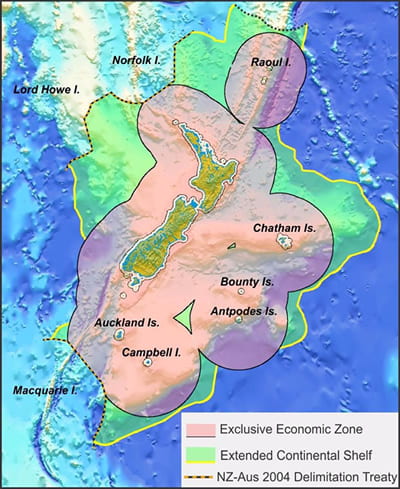

Map showing Aotearoa New Zealand’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Image credit: GNS Science.

Choosing how we focus our data collection and research efforts is critically important. We need to have the right knowledge to progress towards a more sustainable fishing future and to measure whether we are moving in the right direction – while accepting that decisions need to be made in the absence of complete information.

Recent relevant government reports

This report arises from a need to renew our efforts to be at the forefront of sustainable fishing. We note there are others working to address the challenges faced by fisheries and the broader marine environment. These reports have highlighted our gaps in understanding around marine ecosystems and environmental monitoring.

Our marine environment 2019 from the Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ

Stock assessments apply to individual fish stocks so they do not account for interactions between different stocks or interactions with the broader marine environment.”

– Our marine environment 2019, Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ.

Although fisheries decisions can consider direct environmental interactions, e.g. with associated or dependent species, biodiversity or habitats of particular significance to fisheries (if information is available), this is often not the case.

Focusing Aotearoa New Zealand’s environmental reporting system by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE)

Current fisheries management systems have a single-species focus and rarely take into account the effects of fishing on the wider ecosystem. For example, ecosystem changes due to fishing and climate change are rarely explicitly included in the single-species fisheries management carried out in New Zealand.”

– Focusing Aotearoa New Zealand’s environmental reporting system, Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment.

While a focus on assessment of individual stocks does not necessarily mean that wider ecosystem effects are not being taken into account (e.g. through other sections of the Fisheries Act 1996), it similarly does not provide assurance that they are. There is very little explicit, relevant and useable information about ecosystem changes available to fisheries managers beyond what is monitored by fisheries stock assessments.

Te Mana o te Taiao – Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy 2020 by the Department of Conservation

The Department of Conservation also recently published Te Mana o te Taiao – Aotearoa New Biodiversity Strategy 2020. The document provides a strategic direction for the protection, restoration and sustainable use of biodiversity, particularly Indigenous biodiversity, in Aotearoa New Zealand. The strategy and planned approach to implementation are highly relevant to management of our fisheries and marine environment.

Papatūānuku (Earth mother), Ranginui (sky father) and their offspring are in serious trouble, and we urgently need to do a better job of looking after them. The state of nature is a legacy that we leave for future generations.”

– Te Mana o te Taiao 2020, Department of Conservation.

Fisheries Change Programme by Fisheries New Zealand

A regulatory work programme called the Fisheries Change Programme is underway by Fisheries New Zealand to enhance and update the fisheries management system, in response to a review by Fisheries New Zealand in 2015. The successful implementation of electronic reporting across the commercial fishing sector produces far more information than its paper-based predecessor. The opportunity, or challenge, is how to make fullest use of this data in the timeliest way possible. This opportunity provides a potentially greatly expanded role for scientific input into fisheries management. Allocative choices should be specific about the basis for decision making, whether this is based on scientific evidence or on other considerations.

Our report seeks to build on this recent work and provide an evidence base to support policy objectives from the Fisheries Change Programme and other workstreams, as well as suggesting wider recommendations for consideration, prioritisation and implementation as appropriate.

Why fisheries are important

Aotearoa New Zealand benefits from its commercial fishing industry for a number of reasons – it upholds Treaty obligations, contributes to the economy and provides thousands of jobs, while supplying food for people here and overseas. However, these benefits from the industry will only be maintained if our fishing practices are environmentally, economically and socially sustainable. There are many stresses on the marine environment including those from commercial fishing practices (see the section ‘Challenges for the marine environment’). As examined in more detail in later sections, quota owners have a share in perpetual harvest rights for QMS stocks and have an interest in ensuring the integrity of commercial harvest rights and the management system that supports them. While quota owners are incentivised under the QMS to ensure sustainability, this does not always eventuate in practice.

There are also challenges with workforce sustainability and wellbeing, and some deepwater operators are reliant on imported workers (as are many primary industry sectors). The industry faces challenges as society’s expectations change with regard to how food is harvested, how animals are treated and how environmental footprints are reported, monitored, and managed.[32–38]

There are many stresses on the marine environment including those from commercial fishing practices.

We can draw on a wide range of evidence to better understand these issues and how to address them, with a focus on applying innovative new ideas to embed sustainability in our fisheries management system and fishing practices, while upholding Māori commercial fishing rights. These issues are discussed through the following subsections.

Juliet met workers on the filleting line at Talley’s in Motueka.

Māori have an enduring right to fish

The introduction of the QMS in 1986 with the Fisheries Amendment Act was not fully inclusive of Māori. It triggered a protracted legal process in which a forced accommodation of the QMS within the Treaty was eventually agreed by mutual consent of both partners. Thus our fisheries system has Māori Treaty rights fundamentally built into it, resting on the Treaty of Waitangi and embodied in the Fisheries Settlement 1992. Some see the inviolate position of the fisheries settlement as impeding strategic thinking for future Māori participation. Others are more open to evolving the way we fish, so long as this is done in full partnership with iwi, by mutual consent. An overview of some of this history is provided below but more detailed information can be found elsewhere (for example, [39–46]).

The signing of the Māori Fisheries Settlement 1992. From right: Sir Don McKinnon, Tā Tipene O’Regan, Sir Douglas Graham and others involved in negotiations. Image credit: Michael Smith, Dominion Post Collection, National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

The Fisheries Settlement 1992 is seen as having restored Māori commercial fishing rights. Prior to the settlement, the rights had been widely accepted, but never defined in law. In 1987, court action and the ensuing passing of the Māori Fisheries Act 1989 provided an interim settlement whereby 10% of quota species in the QMS at the time were to be bought back by the Crown and transferred to Māori over three years. The Fisheries Settlement 1992 subsequently provided Māori with funds to buy a 50% share of Sealord, including a large share of quota. Government also promised that 20% of any future quota would be allocated to Māori. This reconfigured the economic landscape of Aotearoa New Zealand’s fishing industry. Māori established commercial enterprises, such as Aotearoa Fisheries Limited (trading as Moana New Zealand), which is the sole or joint shareholder of several Aotearoa New Zealand commercial fishing companies. A trust, Te Ohu Kaimoana, was established to advance and advocate for Māori fisheries. Te Ohu Kaimoana and various iwi charitable organisations deliver economic and social benefits to some Māori. In 2011 the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011 was enacted, which provides for the special status of the common marine and coastal area as an area that is incapable of ownership.

The 1992 Fisheries Settlement is seen as having restored Māori commercial fishing rights. Prior to the settlement the rights had been widely accepted, but never defined in law.

As part of the Settlement, Māori endorsed the QMS. The Settlement also restored customary fishing rights, ensured Māori would be appointed to statutory fishing bodies, and agreed to regulate Māori self-management of fishing for communal subsistence and cultural purposes.

However, there are ongoing issues – for example, around the resolution of historic quota management issues, which are known colloquially as ‘28N rights’.[46–48] ‘28N rights’ give holders preferential rights where there are increases in total allowable commercial catch (TACC), which can result in those without these rights (including iwi) having their share of TACC proportionately decreased.[49] These unresolved issues continue to hinder current fisheries management.

As per the Treaty, Māori have perpetual rights to fish and to exert rangatiratanga over their fisheries – maintaining the sustainability of fisheries and their surrounding environment. Sustainability of the fisheries resource is a pillar of these agreements and, to uphold the fundamental rights of Māori, there needs to be a sustainable resource for future generations to fish. Maintaining environmental and ecosystem health in our oceans to meet these obligations is paramount. These rights also mean that the way we achieve sustainable fisheries must uphold the terms of the Fisheries Settlement 1992, unless this is changed by mutual consent of Māori and the Crown. Commentators have highlighted the tensions inherent between kaitiakitanga principles and commercial rights. Dame Anne Salmond comments, “Once again, modernist ideas of ‘property’ and profit have entangled in complex ways with mana and ancestral tikanga relating to the ocean”.[50]

Changes made to fisheries management, including those that shift the focus further towards EAFM, should be made in partnership with Māori. Indeed, they are often in harmony with traditional approaches (see Te ao Māori). A current concern expressed by Te Ohu Kaimoana is that an increasing number of areas are being closed to commercial fishing in the government’s pursuit of a more ecosystem-based fisheries management approach.[45] The importance of a partnership approach to these changes cannot be overstated if we are to facilitate the continuation and strengthening of an effective, legally sound, and authentic co-management approach to improving the sustainability and strengthening the resilience of our fisheries.

Changes made to fisheries management, including those that shift the focus further towards an ecosystem approach to fisheries management (EAFM), should be made in partnership with Māori.

Commercial fisheries contribute to the economy

The marine economy, including commercial fisheries, is a big contributor to Aotearoa New Zealand’s economy. For the 2016-2017 year, the marine economy was estimated to contribute $3.8 billion directly to the economy, as well as an additional $3.2 billon indirectly.[11] Fisheries and aquaculture are estimated to contribute almost a third of this figure. A report prepared for the industry concluded that wild-caught commercial fisheries had a direct economic contribution of $550 million in 2015.[51]

Fisheries contribution to the economy is particularly significant for dispersed regional parts of Aotearoa New Zealand that may otherwise have limited economic opportunities.

Fisheries contribution to the economy is particularly significant for dispersed regional parts of Aotearoa New Zealand.

To grow business, companies need to improve the quality and sustainability of the catch and derive higher value from fish products. There is incentive to innovate, but this is often offset by a complex regulatory environment that sometimes provides perverse incentives for unhelpful practices (see ‘The regulatory space is complex’). A regulatory imperative and/or direct financial gain may drive necessary changes to reduce impact.

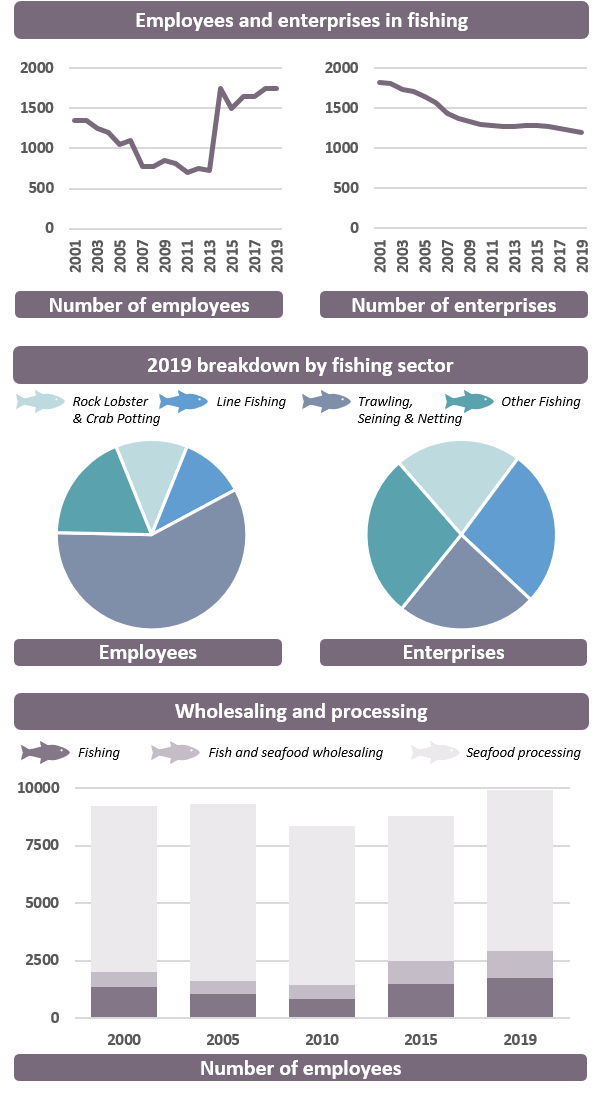

In 2019, the number of businesses in the fishing industry was evenly distributed between four groupings: rock lobster and crab potting; line fishing; trawling, seining and netting; and other fishing.[52] However, by employee count, trawling, seining and netting accounted for over half of employment.

The fishing sector creates more jobs in both processing and wholesaling. In 2019, seafood processing accounted for 7,000 employees, while fishing accounted for 1,750, and fish and seafood wholesaling accounted for 1,150. There are also jobs created in shipbuilding and repair services. Growing the by-product industry has the potential to further increase jobs, discussed later in the section ‘Using the whole fish to develop high-value by-products’.

The continued significant contribution to Aotearoa New Zealand’s economy relies on healthy fish stocks, which themselves rely on healthy ecosystems and habitats. Ensuring that economic pressures or benefits do not outweigh environmental concerns will be crucial for a sustainable fisheries resource.

Ensuring that economic pressures or benefits do not outweigh environmental concerns will be crucial for a sustainable fisheries resource.

Fish is an important part of our diet

Fish is an integral part of the diet in Aotearoa New Zealand, with 91% of New Zealanders purchasing seafood. Forty percent report buying seafood at least once a week, and most of us expect to increase our consumption in the future.[35] Customers from Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand report similar purchasing patterns.[35] In Australia, seafood consumption increased significantly during the last few decades, with one study finding a 45% increase between 1995 and 2011.[53] The Australian experience reflects a worldwide pattern – the demand for seafood is increasing and projected to continue to grow.[54]

Hoki/blue grenadier (Macruronus novaezelandiae) fillets on sale in a supermarket. Image credit: Dave Allen/NIWA.

The demand for seafood is increasing and projected to continue to grow.

According to the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), global per capita fish consumption grew from 9.0 kg (live weight equivalent) in 1961 to 20.5 kg in 2018, and is projected to reach 21.5 kg in 2030, although there is considerable regional variation.[54] Aotearoa New Zealand’s per capita consumption is between 20-30 kg per year.[54] Fishing sustainably now will allow us to keep eating seafood in the future.

The demand for seafood exists because seafood is a relatively healthy source of protein. It is leaner than most red meats and generally higher in essential fatty acids.[25] National dietary guidelines consistently recommend people eat seafood for health benefits.[55]

However, many families cannot afford the cost of highly nutritious foods.[56] This is also true for seafood, for example, an Australian study found seafood intake was lowest in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities.[55] The study also found that lower price-point fish in Australia was less nutritious and had a worse environmental impact. This highlights the need to consider sustainable consumption from environmental, nutrition and socioeconomic perspectives. A comparison of the environmental impact of different forms of food production is outside the scope of this report. However, it is worth noting that aquaculture could assist in filling this role, indeed, aquaculture production now surpasses wild catch worldwide. Reducing reliance on wild-caught fish may be of value, and could also allow sale of wild-caught fish as a premium product (see section ‘Using the whole fish to develop high-value by-products’). Aquaculture is beyond the scope of this report.

Food security and nutritional issues are projected to become important issues globally with the dual impacts of a growing population and climate change.[56] Seafood provides essential local food, livelihoods and export earnings.[57] Many consider that healthy fisheries are important for food and nutrition security, particularly as the impacts of climate change become more apparent.[58]

Fishing sustainably now will allow us to keep eating seafood in the future.

The wellbeing of our fishers matters

The health, safety and wellbeing of fishers and their communities is vital to the ongoing strength and productivity of the commercial fisheries industry. To date, economic and environmental sustainability have been the focus.[59] Broadening this scope to factor in the social aspects of sustainability is important to maintain the wellbeing of the people and communities who make up the industry.

Globally, fishers today are facing the dual pressures of limited fish and more management.[60] Aotearoa New Zealand has its own set of challenges that can place a heavy burden on fishers and their families. As part of the Fisher Wellbeing Programme established in September 2019, the Ministry for Primary Industries commissioned an initial study to understand the wellbeing needs of our local commercial fishing industry. Key needs identified include economic wellbeing, regulation that has the least impact on livelihoods, self-determination on fisheries decisions, identity and sense of belonging, physical and mental wellbeing, and social connectedness.

Pressures that fishers may face include:

- Cost of leasing annual catch entitlement (ACE).

- Cost of operating.

- Negative public perception of fishers.

- Uncertainty around the future of fisheries (catch cuts, access to ACE, further closures etc.).

- Uncertainty around access to fish (whether they will be able to lease ACE in the coming year).

‘Safety first’ sign onboard the RV Tangaroa.

These findings have been used to inform a fisher wellbeing strategy to improve wellbeing and resilience across the sector. The Fisher Wellbeing Programme has five objectives:

- Identify key wellbeing drivers, challenges and opportunities for fishers in New Zealand.

- Facilitate and build cross-sector commitments to fisher wellbeing.

- Increase wellbeing support capacity of frontline Fisheries New Zealand staff.

- Increase regional wellbeing support for fishers.

- Increase resilience of fishers, their whānau and fishing communities.

The timeframe to achieve these outputs is by June 2023, at which point governance of the support network is likely to shift from Fisheries New Zealand to the industry.

A local fisher unloads his catch of snapper on Auckland’s waterfront in the mid-1970s. Image credit: photographer unknown/NIWA.

Some fishers also face barriers to entry into the industry. As with other primary industries, fisheries are managed to maximise value to Aotearoa New Zealand not local communities.[61] It is well documented that the implementation of an ITQ system reduced the number of independent small-scale fishers, which was in part by design to rationalise and increase efficiency in the industry.[62] The level of quota allocated to fishers meant many had to choose between either acquiring further quota or exiting the industry.[63]

Fishing is a business with high infrastructure needs. Since the late 70s the industry has been concentrated: 10% of the vessels caught more than 80% of the fish as the industry was dominated by a number of large operators.[16] The quota system drove further concentration and also placed quota in the hands of non-specialist investors. Roughly 15 years after the QMS was established, over 3,000 predominantly small-scale fishers had exited the industry,[62] largely due to compliance costs, uncertainty about future QMS policy and the high cost of quota.[63] Continued concentration is occurring in the ownership of quota for deepwater species.

At the same time there has been an increase in participation by small-scale fishers in the inshore fishery, apparently driven by the introduction of the ACE.[64] Currently small-scale ACE fishers make up around 80% of the inshore fleet.[61] Financially it can be difficult for independent fishers to compete against companies with vertical integration that own large amounts of quota. That said, these companies do provide an option for independent fishers to operate under an owner-operator model which provides infrastructure and a route to market that may not otherwise be accessible. There are costs and benefits associated with every model of ownership or use.

Roughly 15 years after the QMS was established, over 3,000 predominantly small-scale fishers had exited the industry, largely due to compliance costs, uncertainty about future QMS policy and the high cost of quota.

Fisheries contribute to the wellbeing of coastal communities. The introduction of the QMS shifted the fisher ecosystem towards large-scale operators, based in larger ports, resulting in a loss of local employment in fisheries.[65] This change within the sector came with both positive and negative outcomes. The Faroe Islands provide an example of a fisheries management system that has prioritised social sustainability as highly as ecological and economic sustainability. The wellbeing of our commercial fisheries sector is an important aspect of sustainability that should be considered during fisheries management decisions.

Managing health and safety is important in a risky environment

Work-related fatalities in fishing to from January 2011 to July 2020. Data from WorkSafe NZ.

In 2017, Maritime New Zealand published survey results on health and safety in the commercial fishing sector from perspectives of both workers and employers. Commercial fishing is a high-risk sector, along with other sectors such as agriculture, construction, manufacturing and forestry.

There are relatively high numbers of workers who say that they behave in risky ways, particularly when it comes to working when overtired or when sick or injured.

Over the last ten years there have been 13 work-related fatalities in the fishing sector. The majority have occurred within the ‘fish trawling, seining and netting’ industry categorisation and almost half were classified as a drowning. This compares to 50 work-related fatalities in the forestry sector over the same time period, which has a smaller workforce than fisheries. Worldwide, the number of work-related fatalities among fishers is likely in the thousands, but a precise estimate is difficult to pin down due to patchy data. In the UK, there were 79 work-related fatalities in the fishing industry over the ten-year period from 2008 to 2018.

Health and safety is increasing as a priority for employers. More are saying that formal audits at regular intervals are part of their normal business and that everyone in the business values ongoing improvements.[66] These changes will help to ensure the health and safety of the fisheries workforce.

There is also growing recognition of the mental health challenges faced by fishers globally, although this has not received as much attention as physical health.[60] A 2015 study from Australia found that Australian fishers exhibit poor mental health, including depression, anxiety and self-harm.[67] This was linked to the inherent resource dependence of fishing and uncertainty associated with top-down policy changes, issues also faced in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Society’s expectations are changing

Consumers are increasingly paying attention to the social and environmental dimensions of the food they eat, generating many different responses, including certification programs, watch lists and local/slow food movements. Currently for Aotearoa New Zealand consumers, quality and price rank above ethical considerations and fishing method when choosing seafood.[35] However, an Australian study has shown that when consumers have a good understanding of sustainability in the seafood sector, this becomes the most important factor in their purchasing decision.[68] This suggests that increasing dialogue around seafood sustainability may lead more people to make purchasing decisions based on the sustainability credentials of seafood.

A specific area of concern for some relates to the humane treatment of fish. Advocates for animal rights have highlighted that there is a lack of humane slaughter requirement for wild-caught fish, as reported recently in local media. Commentary on fish welfare is also increasing internationally.

Approaches that make fishing more humane and sustainable, and ways to share that information easily and transparently with customers, will help to maintain demand for wild-caught fisheries from Aotearoa New Zealand. Until these practices become widespread throughout the industry, they may offer a price premium for fishers to motivate good practice (see case study ‘How a commitment to transparency and traceability has generated a premium product’).

Snapper at Lee Fish in Leigh, north of Auckland. Every fish shipped from here is accompanied by a code (top left of box) that traces back to the fisher and vessel that caught the fish.

Approaches that make fishing more humane and sustainable, and ways to share that information easily and transparently with customers, will help to maintain demand for wild-caught fisheries from Aotearoa New Zealand. These changing demands provide impetus to innovate to make fishing more humane and sustainable.

We can build on the QMS to improve sustainability

For over 30 years, Aotearoa New Zealand’s fishing legislation has recognised that our fisheries resources are finite and has provided a framework based around the purpose of providing for the “utilisation of fisheries resources while ensuring sustainability”. This is the foundation of the QMS and Aotearoa New Zealand’s current legislative and management approach to fisheries.

The QMS aims to preserve fish stocks for future generations by creating a long-term stake in the fishery which could help offset short-term economic pressures that can result in severely depleted fish stock.[69, 70] However, there is a complex interplay between economic incentives and regulatory requirements that impact on achieving sustainable utilisation of fish stocks while also addressing broader environmental and societal goals. The consideration of ecosystem impacts is provided for under the Fisheries Act 1996[71, 72] and where considerations are given affect this allows for the management of fishing to become more rigorous and nuanced. However, implementation has been variable and we can do better.

The fundamental challenge faced by all those focused on a sustainable fishing goal is to translate an incomplete but increasingly sophisticated understanding of the complex interactions and cumulative pressures on our ecosystems into effective and actionable policies and regulations, along with robust indicators to monitor progress.

This ambitious goal is likely to take some time to achieve and demands strong leadership by the fisheries management agency, and a connected community of stakeholders with a shared vision of the future.

The current fisheries management regime has mechanisms that can enable an ecosystem approach. Aotearoa New Zealand has already incorporated some aspects of ecosystem-based approaches into fisheries management alongside the QMS,[73] often through the use of fisheries plans. For example, the Draft National Inshore Finfish Fisheries Plan, released for consultation in November 2019, suggests certain ecosystem approaches to fisheries management, such as integrating management of multiple stocks caught within a fishery, that could be applied in future. However, this plan is yet to be implemented.

The New Zealand Government has committed to taking an ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management that integrates sustainable harvesting with wider biodiversity considerations.[74] Local research to foster ecosystem thinking in Aotearoa New Zealand’s fisheries management system is underway as part of Sustainable Seas (see case study), but more work is needed to integrate the research and policy intent with community knowledge, and to translate lofty goals to day-to-day decision making in the fisheries management system and practice in our oceans.

Perhaps the fundamental challenge faced by all those focused on a sustainable fishing goal is to translate an incomplete but increasingly sophisticated understanding of the complex interactions and cumulative pressures on our ecosystems into effective and actionable policies and regulations, along with robust indicators to monitor progress. This ambitious goal is likely to take some time to achieve and demands strong leadership by the fisheries management agency, and a connected community of stakeholders with a shared vision of the future. However, it offers an opportunity to be world leaders in managing future commercial fisheries.

This report aims to address this challenge by focusing on how we can fill data gaps, translate data into knowledge, and draw on new innovations to inspire the development of a fisheries management system within the Fisheries Act 1996 that enables more sustainable commercial fishing practices.

This underpins recommendations in Themes 4-7.

Guiding frameworks and exemplars

Addressing the challenge of building an environmentally, socially and economically sustainable commercial fisheries industry requires overarching frameworks to guide our thinking. This report has been guided by different frameworks, intimately connected by their holistic systems approach. Te ao Māori, the Māori worldview, has long recognised the interconnectedness of all things and the need to address complex issues in a holistic way.

Additionally, regulatory and management approaches to our marine environment – both here in Aotearoa New Zealand and overseas – increasingly aspire to an ecosystem approach. We can look to exemplars overseas for inspiration and ideas to enhance our commercial fisheries. This section includes a brief overview of international jurisdictions that, alongside Aotearoa New Zealand, are known for their best practice fisheries management.

Te ao Māori

As an island nation populated by talented seafaring tūpuna, the ocean is of special importance to Māori. This is reflected in strong Māori views on fisheries management, drawing on tikanga to fulfil the role as kaitiaki of our oceans. For example, interviews with 22 kaitiaki from 14 North Island iwi found that they share common concern about the decline in abundance and diversity of kaimoana.[75] This concern extends beyond ecological health, to cultural ramifications. Declining kaimoana leads to fewer opportunities for iwi, hapū and whānau to work communally, and to share stories and mātauranga across generations. The loss of signature kaimoana affects the ability of iwi to practice manaakitanga (hospitality, generosity), which in turn results in a loss of mana and identity.

As an island nation populated by talented seafaring tūpuna, the ocean is of special importance to Māori.

The Māori Fisheries Settlement 1992 vests management of large portions of our fisheries with iwi, again reflecting the significance of kaimoana in Māoridom. As discussed earlier, around 27% of fisheries quota are owned by Māori and three of the five biggest fishing companies in Aotearoa New Zealand are Māori-owned.[23, 24]

Wisdom from te ao Māori offers a knowledge framework that is in many ways orthogonal to that of western science.[76] Te ao Māori sits on a foundation of mātauranga Māori, which takes holistic view of the natural world, valuing deep community knowledge as well as more quantitative approaches. Mātauranga also incorporates both knowing and doing. In the marine environment, where scientific knowledge is naturally limited by the inaccessibility of elements of interest, mātauranga Māori has special value. Some important concepts within te ao Māori include:

- Tikanga – the right way of doing things; defines how mātauranga is put into practice.

- Kaitiakitanga – guardianship, or an ethic of environmental care.[77]

- Rangatiratanga – self autonomy and independence.

- Whanaungatanga – a sense of kinship and belonging that develops through working together.

- Manaakitanga – generosity and hospitality.

A more detailed explanation of te ao Māori and related concepts can be found in Reid et al.[22]

Western science and te ao Māori offer complementary lenses with which to view the world and solve problems. Drawing on both frameworks in partnership offers a unique strength to policymakers charged with managing our marine environment.

In particular, the concept of ‘ecosystem thinking’ has synergies with mātauranga Māori. While much of western science has relied on reductionist thinking, ecosystem thinking requires deep knowledge of entire systems and how complex interrelationships between component parts drive the emergent properties of the whole (see ‘Ecosystem thinking’). However, conflicts between some aspects of ecosystem-based approaches and te ao Māori remain: for example, some seek to couch ecosystem services in econometric terms, whereas Māori perspectives may lend more weight to cultural and spiritual considerations.[22]

The concept of ‘ecosystem thinking’ has synergies with mātauranga Māori.

A key difference between te ao Māori and the western worldview is their respective approaches to conservation. Traditionally, western conservation can often involve preservation of the environment separate from human activities, whereas Māori view humans as an integral part of the environment, with the role of kaitiaki. In the context of fisheries, this can create divergent views about whether permanent ‘no-take’ protected areas are appropriate, with a Māori view more likely to manage populations with limited take (though there are of course exceptions, see section ‘Iwi initiatives’), through a series of rāhui defined in space and time to nurture all populations. Rāhui are just one approach in the mātauranga toolbox. Other practices include rotational use of mahinga kai (food gathering areas), harvesting smaller individuals to protect breeding stock, protection of kōhanga (nursery areas) and active translocation/reseeding.[75] In some ways these tools foreshadowed multiple-use protection areas used widely overseas.[78]

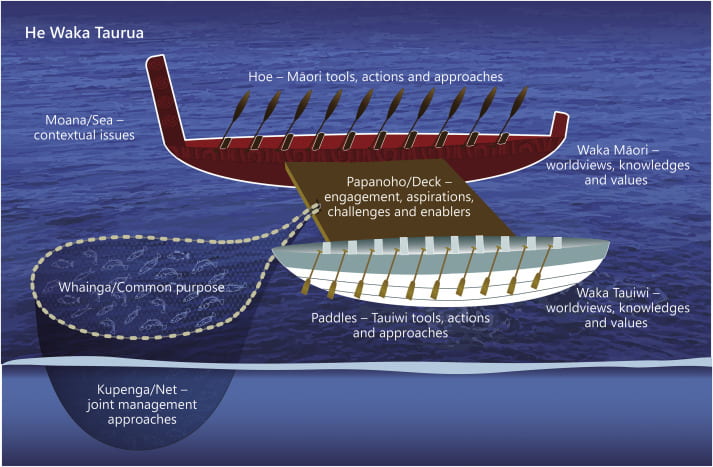

He Waka-Taurua framework for recognising multiple worldviews to achieve holistic co-governance/co-management. Image from [79]. Click to enlarge.

Recent research has explored the Māori perspective of fisheries management and sought to effectively integrate te ao Māori and western science for true collaboration and co-governance. The Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge has published work in this area while also embracing the partnership model in practice.[77, 79]

One outcome of these efforts is the He Waka-Taurua model, a metaphorical framework for marine co-management.[79] A waka-taurua consists of two waka temporarily lashed together to achieve a common purpose (see figure above).

Another useful metaphor is ‘He Awa Whiria‘, which refers to the multiple, interconnecting channels in a braided river.[80] In this approach, multiple worldviews and scientific disciplines interweave to support actions and interventions. It recognises separate but equally valid knowledge systems – like two sources feeding into a single braided river – that mix to generate new understanding. The ‘He Awa Whiria’ approach was applied in the development of Te Mana o Te Taiao – Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy 2020.

In the research space, the policy framework Vision Mātauranga aims to “unlock the potential of Māori knowledge”.[81] It is the guiding policy for the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) and is incorporated into the operating principles of CRIs.

There are a range of other tools and frameworks that have been developed for agribusiness that could be useful for working with te ao Māori alongside western environmental management and research.[82, 83]

- Mauri Compass Tool: for understanding the mauri (essential quality and vitality of a being or entity) of a waterbody and interconnected parts of its system. It involves using standardised tests to assess 12 parameters (referred to as compass points), assigning a value for each from one to five. The assessment of tangata whenua, wairua, mahinga kai, and culture can only be assigned by tangata whenua. The others draw on western science and include habitat, biodiversity, water biology, water chemistry, freshwater eel/tuna[84] growth rates, freshwater eel species, abundance and population, and biological health.

- Te Mauri Model Decision Making Framework: The ‘mauri-o-meter’ is a tool that assesses the impact of practices or activities on the mauri of a resource and attributes scores and weightings to each. The wellbeing factors are interconnected and include: mauri of the whānau (family, economic), community (social), hapū (cultural) and ecosystems (environment). The framework supports decision making by integrating quantitative and qualitative data and providing a sustainability assessment.

- Cultural Health Index (CHI)[85]: A Māori-led and developed tool to monitor change in a specific environment based on three components: 1) whether the site has traditional significance to tangata whenua (yes/no); 2) a qualitative assessment of the mahinga kai (natural resources) of the site; 3) a stream health index made up of qualitative ordinal rankings. The tool is adaptable for different environmental domains.

- Te ao Māori framework for environmental reporting[86]: This scoping document includes a series of measures for environmental monitoring that align with te ao Māori values and would give full voice to the Māori worldview for reporting on environmental impacts.

Successful partnerships of Indigenous and western knowledge have occurred both here in Aotearoa New Zealand and overseas. Some examples are outlined below. Effective co-governance examples have several characteristics in common: key among these is that Indigenous people and their perspectives must be included at the very beginning of a programme or initiative. There is a power imbalance between western and Indigenous worldviews, and Māori must have rangatiratanga or power within co-governance frameworks for meaningful implementation of te ao Māori principles.[22,87]

Aotearoa New Zealand examples:

- Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari brought together stakeholders across Tīkapa Moana the Hauraki Gulf to develop a marine spatial plan, aiming to restore the mauri of the Gulf.[88] This was a complex undertaking with a wide array of iwi, enterprises and voices contributing to the development of the plan over four years and not without tensions. The Māori worldview was incorporated into the eventual spatial plan. The Government appointed a Ministerial Advisory Committee to help shape their response to the conservation and fisheries related proposals in the spatial plan, which is pending (see case study ‘Managing land-based impacts through a multi-sector marine spatial plan’).

- The community group Kaikōura Coastal Marine Guardians (Te Korowai) developed a management strategy for the Kaikōura marine environment in 2012.[79] This was built around four pillars, including ‘sustaining customary practices’, which aimed to restore and maintain Ngātī Kurī’s traditional fishing areas, tikanga and mātauranga. The strategy was enacted through the Kaikōura (Te Tai ō Marokura) Marine Management Act 2014. This legislation also made the Kaikōura Marine Guardians a statutory body, appointed by Ministers to advise on issues affecting the Kaikōura marine environment, but required a specific act of Parliament (see case study ‘Te Korowai o te tai ō Marokura in Kaikōura shows how regional responsibility can streamline fisheries management’).

- He korowai o Matainaka – in this project, traditional ecological knowledge was merged with scientific understanding and engaged the mana whenua Kāti Hauirapa to improve management of īnaka/whitebait[89] spawning and mahika kai sites along the Waikōuaiti River in Otago.[90] “What really counts in an ever changing world is the re-engagement between people and the environment that will reinstate mātauraka[91] Māori processes into contemporary mahika kai management relationships and practices… the knowledge will be combined with science to ensure the most beneficial adjustments are made for efficient and sustainable future environmental management.”

- The Moana Project brings together iwi, Māori academics and other researchers, and the seafood sector to develop sensors and knowledge exchange platforms to gather oceanographic data.[92] It is envisaged that data collected will feed into models and lead to more efficient and informed forecasting and decision making (see case study ‘The Moana Project – arming vessels with sensors to help validate ocean models’).

What really counts in an ever changing world is the re-engagement between people and the environment that will reinstate mātauraka Māori processes into contemporary mahika kai management relationships and practices… the knowledge will be combined with science to ensure the most beneficial adjustments are made for efficient and sustainable future environmental management.”

The Haida Gwaii Marine Plan was co-developed by the Haida Nation and the Province of British Columbia in Canada.

Indigenous knowledge features in marine management in many places around the world, for example:

- In Canada, the Haida Gwaii Marine Plan released in 2015 was co-developed by the Haida Nation and Province of British Columbia. The plan is founded on Haida ethics and values, and outlines how these relate to principles of ecosystem-based management.

- The Hui Mālama o Mo’omomi people of Hawaii designed and implemented their own management plan that exerts their traditional stewardship, incorporating scientific assessments.[79]

- In December 2018, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council of Alaska adopted a Bering Sea Fishery Ecosystem Plan that explicitly incorporates Indigenous knowledge into decision making. Communities in the Bering Strait region have vast knowledge of local ecosystems passed down for millennia.

The potential of a holistic long-term approach in the marine environment is underscored in Theme 3 recommendations.

International best practice

Although reviewing international fisheries management is beyond the scope of this report, throughout our research and discussions with stakeholders, a handful of jurisdictions were repeatedly held up by multiple people alongside Aotearoa New Zealand as leading in aspects of commercial fisheries.[93] We can look to parts of these international fisheries management systems for inspiration to improve the sustainability of our fisheries, with the caveat that they are not universally accepted as gold standard by all parties.

Each region takes a unique regulatory and management approach, from which we draw specific elements for inspiration below.

Fresh catch on the dock in Seward, Alaska. Image credit: Arthur T. LaBar/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Iceland

Icelandic fisheries management has a rights-based system very similar to Aotearoa New Zealand’s but with important differences. Each stock is managed through an annual TAC, with individual operators having ITQs based on their quota allocation. The government later introduced a resource rent tax which has changed over the years but requires the industry to pay fees to access fishing resources.[94] Trust is built through independent fish surveys. Fisheries data is widely accessible.

In recent years, the Icelandic fishing industry has focused heavily on the use of fish by-products.[95, 96] While the volume of fish caught in Iceland has decreased over the past few decades, their export value has increased. Much of their success in this area appears to be due to an organisation called the Iceland Ocean Cluster and their 100% Fish Project (discussed in detail in ‘Using the whole fish to develop high-value by-products’).

The Icelandic fishing industry has focused heavily on the use of fish by-products. While the volume of fish caught in Iceland has decreased over the past few decades, their export value has increased.

Alaska, US

Alaskan fisheries management differs by stock, based on a mix of federal and state policies. The North Pacific Fishery Management Council has authority to determine how the federal legislation will be implemented for Alaska’s fisheries and sets an annual TAC. Management is guided at the federal level by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and national standards for fishery conservation and management. NOAA has developed an Integrated Ecosystem Assessment initiative to guide effective ecosystem-based management (see case study ‘Integrated ecosystem assessments to inform ecosystem-based fisheries management’) which Alaska is beginning to apply, starting with conceptual models.[97]

In Alaska, fishers have come together to share data in order to allow real-time identification of hotspots to avoid for bycatch. This example is discussed in the section ‘Dynamic ocean management will help protect non-target species in real time’.

In Alaska, fishers have come together to share data in order to allow real-time identification of hotspots to avoid for bycatch.

British Columbia, Canada

Fisheries management in British Columbia, Canada, is based on a mix of federal and state policies. The ITQ management approach was introduced around five years after Aotearoa New Zealand’s own QMS system. These management approaches are similar.

British Columbia implemented an innovative bycatch quota system for bycatch in the Trawling Groundfish Fishery (Area 2B) in 1996.[98] On top of the ITQ, this fishery has also had an individual vessel bycatch quota system paired with a 100% mandatory observer programme. This allows a specified proportion of their TAC to be comprised of bycatch. Fishers made changes to their fishing operations in response, for example through reduced towing time, improved handling of discarded fish, and increased selectivity in their operations. Edinger and Baek[98] found that the use of individual vessel bycatch quota was highly effective at mitigating bycatch in this fishery, though recommend caution and careful consideration in applying this approach to other fisheries.

Trawlers in British Columbia. Image credit: Geoff Sowrey/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Norway

A new Marine Resources Act came into force in Norway in 2009 representing a paradigm shift in fisheries management for the country by mandating the application of EAFM.[99] The industry is highly regulated with quotas and licensing requirements.

An Atlantis ecosystem model of the Norwegian and Barents Sea has been developed (see section ‘Models can support ecosystem approaches to fisheries management’).[100, 101] Although there is a long way still to go, some of the management takes into account multi-species fisheries and interactions between species. For example, management of capelin[102] takes into account the importance of capelin for Northeast Arctic cod.[103–105] There are multispecies considerations in setting catch levels on several of the main fisheries (cod, haddock[106], capelin) and some level of balance between fishing of high trophic level and low trophic level species.[107]

Norway is undertaking some exciting new innovative management techniques, including the use of genetic techniques to regulate cod fisheries in real time. This is discussed in the case study ‘Real-time genetic management of a marine fishery’.

Norwegian fishing vessels. Image credit: Javier Rodríguez/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Australia

In Australia, there are eight different jurisdictions each with their own fisheries legislation.[108] The Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) works with state/territory government agencies to meet sustainability objectives. Many fisheries in Australia are ITQ-based, mostly single-species but some multi-species fisheries.[109] Some fisheries activities are defined as ‘threatening processes’ under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. These include ‘incidental catch (or bycatch) of seabirds during oceanic longline fishing operations’, ‘incidental catch (or bycatch) of sea turtle during coastal otter-trawling operations within Australian waters north of 28 degrees south’, and ‘injury and fatality to vertebrate marine life caused by ingestion of, or entanglement in, harmful marine debris’. Australia has established spatial closures for gillnet fisheries in certain areas to protect Australian sea lions[110] in their habitat and breeding colonies. There is also a gillnet dolphin mitigation strategy aiming to empower fishers using gillnets to avoid and mitigate dolphin interactions.

Faroe Islands

In the Faroe Islands, fisheries management reform that came into effect in 2018 recognises all living marine resources in the Faroese waters as the property of the Faroese people. This is in some ways the opposite of quota management where quota rights are held by individuals (although quota rights do not create a property right in fish, but only a right to harvest a proportion of the TACC). Prior to the reform, limited access and prioritising social outcomes led to stock decline.[111] Policy changes that seek to balance ecological, economic and social sustainability appear to be able to achieve that.[112] The historical and cultural context of the Faroe Islands is very different than Aotearoa New Zealand and may have limited relevance. The Faroese Ministry of Information has further information on recent and ongoing reforms in the management of their fisheries.

Fisheries management reform that came into effect in 2018 recognises all living marine resources in the Faroese waters as the property of the Faroese people.

Blue economy

A term that is sometimes used to capture a holistic approach to managing human use of the oceans is ‘blue economy’. This is not a framework that we have adopted in this project, but the thinking has informed our approach and views.

There is no widely accepted clear definition of the term ‘blue economy’. It is sometimes used interchangeably with ‘ocean economy’ or ‘marine economy’ and some argue that this lack of agreed definition limits its utility.[113] Some definitions are in the table below.

Definitions of 'blue economy' from a range of sources.

| Definition | Source |

|---|---|

| “The Blue Economy conceptualises oceans as ‘Development Spaces’ where spatial planning integrates conservation, sustainable use, oil and mineral wealth extraction, bio-prospecting, sustainable energy production and marine transport.” | United Nations |

| “The ‘blue economy’ concept seeks to promote economic growth, social inclusion, and the preservation or improvement of livelihoods while at the same time ensuring environmental sustainability of the oceans and coastal areas.” | World Bank |

| An economy “comprised of activities that will generate economic value and contribute positively to social, cultural and ecological wellbeing”. | Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge |

“A sustainable blue economy is a marine-based economy that:

| World Wildlife Fund |

| “The ‘Blue Economy’ is an emerging concept which encourages better stewardship of our ocean or ‘blue’ resources.” | The Commonwealth |

The narrowest definitions tend to focus on value extracted from ‘use’ (e.g. through commercial fishing, aquaculture, tourism, minerals) while broader definitions encompass ‘non-use’ value associated with ecosystem services and biodiversity. Many descriptions also include reference to sustainability and responsible stewardship.

Stewardship of the oceans is not straightforward. Unlike the land, few parts of the ocean are permanently owned or occupied. Use of the ocean is temporary and non-exclusive, with multiple uses in the same space over time. Conceptions of the blue economy focus on holistic, ecosystem-based approach to the whole ocean, rather than individual aspects.[114, 115]

Unlike the land, few parts of the ocean are permanently owned or occupied. Use of the ocean is temporary and non-exclusive, with multiple uses in the same space over time.

Like land-based natural resource enterprises, social and cultural acceptance (or ‘social licence to operate’) is integral to enacting a truly transformative blue economy.[116] Social licence to operate has proved challenging for some marine industries in Aotearoa New Zealand, such as salmon aquaculture farms in Te Tauihu-o-te-waka the Marlborough Sounds.[117]

Activities that comprise Aotearoa New Zealand’s blue economy include, but are not limited to:

- Fishing of wild fisheries (commercial, recreational and customary),

- Aquaculture,

- Ecotourism and recreation,

- Shipping/maritime transport, plus activity at ports and marinas,

- Offshore minerals, and

- Offshore energy production.

As the nature and scale of activities in Aotearoa New Zealand’s maritime area shifts, we will need to make informed and integrated decisions about how, where and when those activities proceed.

Ecotourism is also part of a ‘blue economy’. A Bryde’s whale surfaces next to a whale watching boat in Tīkapa Moana the Hauraki Gulf. Image credit: Aucklandwhale/Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge

In Aotearoa New Zealand, ‘creating value from a blue economy’ is one of the core research themes for the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge. This theme is underpinned by four key ideas:

- Societies will rely on the oceans for future food, energy and economic security.

- Oceans offer economic development potential.

- Realising this potential requires investment in science and technology.

- We must transition to sustainable growth.[115]

Research emerging from this theme has mapped Aotearoa New Zealand’s growing marine economy, visualised the complex interconnections and feedback loops inherent in marine enterprises, and envisaged new categories to help us rethink management of the economy.[118–120]

An economic analysis commissioned by Sustainable Seas estimated that ‘blue economy’ activities contribute around 3% to our GDP and employ around 70,000 people (3.3% of total employment).[121] The analysis showed that tourism was growing (pre-COVID-19), offshore oil and gas exploration was declining, while aquaculture was poised for growth.

As the ‘blue economy’ concept has originated overseas, adapting it for the Aotearoa New Zealand context requires some work. For example, an Indigenous worldview is not explicit within most blue economy frameworks, but here in Aotearoa New Zealand it makes sense to incorporate a te ao Māori lens (see Te ao Māori).[44] Sustainable Seas has identified other unique Aotearoa New Zealand drivers for a blue economy, including our export market, green premiums, and capital/wellbeing approaches to central and local government.[115] Use of this concept more widely would require a definition of blue carbon for use in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre

An Australia-based initiative, the Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre aims to bring together stakeholders in the seafood, aquaculture, marine renewable energy and offshore engineering sectors to address the challenges of offshore food and energy production. Several Aotearoa New Zealand-based organisations are partners of the Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre, including New Zealand King Salmon, AUT, Plant & Food Research, Cawthron Institute and the University of Auckland.

Ecosystem thinking

Protecting ecosystem structure and functioning is critical to ensure a sustainable future for the fishing industry. Fisheries management in Aotearoa New Zealand generally views each species of interest in isolation, although the Fisheries Act 1996 does enable wider consideration of ecosystem impacts to be taken into account in fisheries management decisions (see section ‘We need a plan for our oceans’). Our current system primarily relies on measuring the stock sustainability of individual commercially fished species to determine how many can be caught. This provides a critical tool in fisheries management, and a certain level of reassurance of overall ecosystem health if all the stocks remain plentiful over an extended period of time.

We need to measure and monitor more parts of the ecosystem and the interactions among them, across different trophic levels, to truly understand ecosystem health and mitigate the risk of ecosystem collapse.

But there are also limitations: a catalogue of single-species measures alone does not capture the full picture (see section on commercial fisheries in 2020). First of all, there may be large uncertainties associated with stock assessments, especially for small fisheries where data gathering is poorly resourced or even with data the species is hard to assess. Beyond this, complex interactions are at play within an ecosystem. Long-term resilience of stocks to heavy fishing might require a more complete set of data which reflects the capacity of the marine environment to sustain the fisheries stock. Looking at a collection of single species as a measure for ecosystem health is limited. It is analogous to monitoring spending as a measure for financial health, without looking at debt. We need to measure and monitor more parts of the ecosystem and the interactions among them, across different trophic levels, to truly understand ecosystem health and mitigate the risk of ecosystem collapse. An explicit ecosystem approach builds on the best practice of experienced fishers who understand their environment after many years of observation. We found examples where this works well and include them to inspire more widespread adoption of these practices.

We have used ecosystem thinking as a guiding framework for this report in conjunction with a te ao Māori worldview. Through an ecosystem lens, we recognise the need to monitor the pressures we put on our marine environment while we build better understanding of the interconnections between parts of the system. We also recognise that there are social and economic dimensions to fisheries that interact with the ecosystem that need to be part of our thinking. The case study ‘Fiordland created a novel model for managing the marine area’, is seen by some as an example of where an EAFM has been successful, from both a fisheries and biodiversity perspective.

There are no ‘off-the-shelf’ measures to reassure regulators that ecosystems are well managed, and local knowledge will be vital in translating these general principles into action.

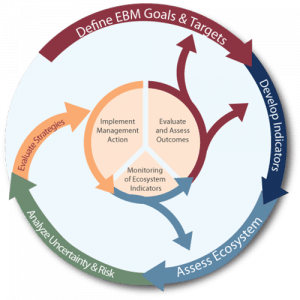

Incorporating measures of ecosystem health may lead regulators down an EAFM path. EAFM can be defined in many different ways.[122, 123] Fisheries New Zealand has described it as an “integrated approach to managing the competing values and uses of fisheries resources while maintaining the ecosystems that support them”.[124] Challenges in implementing EAFM include having robust methods for recognising when an ecosystem is adversely impacted, understanding direct and indirect effects of fishing one species on other ecosystem components, reconciling multiple fisheries operating under different management systems, and identifying indicators that can deliver useful information for these management systems.[125] There are no ‘off-the-shelf’ measures to reassure regulators that ecosystems are well managed, and local knowledge will be vital in translating these general principles into action.

This underpins recommendations in Theme 6.

References and footnotes

[1] New Zealand Government (2019) Aquaculture Strategy, p. 20.

[2] Wynne-Jones, J. et al. (2019) National panel survey of marine recreational fishers 2017–18, New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2019/24.

[3] Southwick, R. et al. (2018) Estimating marine recreational fishing’s economic contributions in New Zealand, Fisheries Research, 208, pp. 116–123.

[4] New Zealand Marine Research Foundation (2016) Recreational fishing in New Zealand: A billion-dollar industry.

[5] Pargus auratus. Note the taxonomic status of this species is being debated, and it may also be referred to as Chrysophrys auratus.

[6] OpenSeas (2017) Seafood risk assessment New Zealand snapper fishery.

[7] Arripis trutta. The Kermadec species Arripis xylabion is found seasonally in Northland waters.

[8] Seriola lalandi lalandi.

[9] Hauraki Gulf Forum (2020) State of our Gulf 2020. Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana/Te Moananui-ā-Toi State of the Environment Report 2020.

[10] Wehi, P. et al. (2013) Marine resources in Māori oral tradition: He kai moana, he kai mā te hinengaro, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, (2), pp. 59–68.

[11] Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ (2019) New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series: Our Marine Environment 2019.

[12] Bess, R. (2001) New Zealand’s indigenous people and their claims to fisheries resources, Marine Policy, 25(1), pp. 23–32.

[13] Matthews, B. (2018) Ko Au Te Moana, Ko Te Moana Ko Au: Te Rangatiratanga Me Te Kaitiakitanga o Roto i Te Rāngai Kaimoana Māori; I Am The Ocean, The Ocean Is Me: Rangatiratanga and Kaitiakitanga in the Māori seafood sector, p. 101. A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of International Relations and Diplomacy, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand.

[14] Paulin, C. D. (2007) Perspectives of Māori fishing history and techniques, Ngā āhua me ngā pūrākau me ngā hangarau ika o te Māori, Tuhinga, 18, pp. 11–47.

[15] McClintock, W. et al. (2000) Retreat from the frontier: Fishing communities in New Zealand, in 8th International Symposium on Society and Resource Management. Bellingham, Washington, USA.

[16] Cullen, R. and Memon, P. (1990) Impact of the exclusive economic zone on the management and utilisation of the New Zealand fishery resources, Pacific Viewpoint, 3(1): 44-62.

[17] This brief history does not attempt to catalogue the range of management options that have been tried over the preceding decades (see for example, Gibbs, M. (2008) The historical development of fisheries in New Zealand with respect to sustainable development principles, The Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development, 1(2), pp. 23–33.)

[18] Mace, P. M. et al. (2014) The evolution of New Zealand’s fisheries science and management systems under ITQs, ICES Journal of Marine Science, 71(2), pp. 204–215.

[19] Hughey, K. P. D. (1997) Fisheries management in New Zealand: Privatising the policy net to sustain the catch?, Environmental Politics, 6(4), pp. 140–149.

[20] McKoy, J. (2006) Fisheries resource knowledge, management, and opportunities: Has the Emperor got no clothes?, New Zealand’s ocean and its future: Knowledge, opportunities and management, pp. 35–44.

[21] Lock, K. and Leslie, S. (2007) New Zealand’s Quota Management System: A history of the first 20 years, Motu Working Paper 07-02.

[22] Reid, J. et al. (2019) Mapping the Māori marine economy: Whai rawa, whai mana, whai oranga: Creating a world-leading indigenous blue marine economy, Wellington, New Zealand, Sustainable Seas: National Science Challenge.

[23] Inns, J. (2013) Māori in the seafood sector (fisheries and aquaculture) – the year in review, Māori Law Review.

[24] Tuuta, J. and Tuuta, D. (2018) Building on the Fisheries Settlement: Te Ohu Kaimoana.

[25] Thurstan, R. H. and Roberts, C. M. (2014) The past and future of fish consumption: Can supplies meet healthy eating recommendations?, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 89(1–2), pp. 5–11.

[26] Bess, R. and Rallapudi, R. (2007) Spatial conflicts in New Zealand fisheries: The rights of fishers and protection of the marine environment, Marine Policy, 31(6), pp. 719–729.

[27] Pomeroy, R. et al. (2007) Fish wars: Conflict and collaboration in fisheries management in Southeast Asia, Marine Policy, 31(6), pp. 645–656.

[28] Winder, G. M. and Rees, E. (2010) Fish and boats: Fisheries management issues in Northland, New Zealand Geographer, pp. 152–168.

[29] Peart, R. (2018) Voices from the Sea: Managing New Zealand’s fisheries, Environmental Defence Society.

[30] Said, A. et al. (2018) The contested commons: The failure of EU fisheries policy and governance in the mediterranean and the crisis enveloping the small-scale fisheries of malta, Frontiers in Marine Science, 5, pp. 1–10.

[31] Grip, K. and Blomqvist, S. (2020) Marine nature conservation and conflicts with fisheries, Ambio, 49(7), pp. 1328–1340.

[32] Sanford sustainable development reporting case study

[33] Ponte, S. (2012) The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and the making of a market for “Sustainable Fish”, Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(2–3), pp. 300–315.

[34] Jaffry, S. et al. (2016) Are expectations being met? Consumer preferences and rewards for sustainably certified fisheries, Marine Policy, 73, pp. 77–91.

[35] Ministry for Primary Industries (2019) New Zealand seafood consumer preferences: A snapshot, p. 28.

[36] Campbell-Arvai, V. (2015) Food-related environmental beliefs and behaviours among university undergraduates a mixed-methods study, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 16(3), pp. 279–295.

[37] Kaiser, M. J. (2019) Recent advances in understanding the environmental footprint of trawling on the seabed, Canadian Journal of Zoology, 97(9).

[38] Alonso, M. E. et al. (2020) Consumers’ concerns and perceptions of farm animal welfare, Animals, 10(3), pp. 1–13.

[39] Boast, R. (1999) Maori fisheries 1986-1998: A reflection, Victoria University of Wellington Law Review.

[40] Johnson, D. and Haworth, J. (2004) Hooked: The story of the New Zealand fishing industry, Christchurch, New Zealand: Hazard Press for the Fishing Industry Association.

[41] Toki, V. (2010) Adopting a Maori Property Rights approach to Fisheries, New Zealand Journal of Environmental Law, 14, p. 197.

[42] De Alessi, M. (2012) The political economy of fishing rights and claims: The Māori experience in New Zealand, Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(2-3), pp. 390–412.

[43] Wheen, N. and Hayward, J. (2012) Treaty of Waitangi Settlements, Bridget Williams Books.

[44] Bargh, B. J. (2016) The struggle for Māori fishing rights: te ika a Māori, Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand: Huia Publishers.