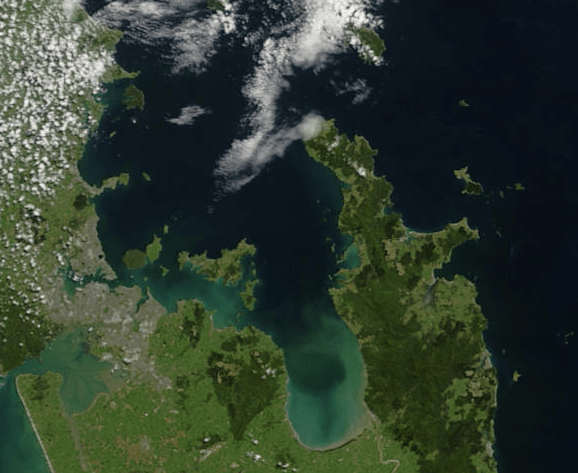

Tīkapa Moana the Hauraki Gulf is a national taonga that surrounds Aotearoa New Zealand’s most populous region. It has been under stress for many decades. The stressors on the marine environment of Tīkapa Moana the Hauraki Gulf are multifaceted, cumulative and increasing. To date, traditional management approaches have failed to reduce the ongoing ecological degradation.

Traditional management approaches have failed to reduce the ongoing ecological degradation.

Recognising this, the Hauraki Gulf Forum was established in 2013 through the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act 2000 as an independent group with representatives of all agencies involved in managing the Gulf to work collaboratively to find a solution to improve and protect the Gulf and better manage its resources.[1] A steering group that included representatives from mana whenua, Auckland Council, Waikato Regional Council, the Department of Conservation, the Ministry for Primary Industries and the Hauraki Gulf Forum guided the process known as Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari. A stakeholder working group developed an agreed plan of action, although the process was not without tensions.

The project culminated with the publication of a Hauraki Gulf marine spatial plan – Aotearoa New Zealand’s first marine spatial plan. The plan outlines a range of proposals to respond to the environmental decline in the gulf (as highlighted in the case study: The Noises vs Cape Rodney-Okakari Point Marine Reserve). It was developed as an integrated package to be implemented as a whole.

Excessive sediment run-off from the land was identified a main stressor on Tīkapa Moana the Hauraki Gulf, along with fishing, causing degraded marine habitats in estuaries, harbours and the inner gulf. The consensus was that it would take a range of actions that could act in concert to reduce soil erosion, minimise sediment entering waterways and stabilise sediment once it has reached the marine environment to reduce the negative impacts and restore the health of the Gulf.

The specific recommendations were to:

- Develop catchment management plans so that there is guidance on what to do for each unique catchment.

- Establish catchment sediment load limits to make sure there are achievable targets that will lead to improvement over time and to facilitate compliance monitoring.

- Increase sediment traps in contributing freshwater waterways by reinstating natural or engineered wetland systems to reduce the impacts of any loss of sediment that does occur.

- Manage waterways to reduce the amount of sediment and contamination making it in by changing land use, planting trees around waterways and developing infrastructure.

- Ensure good sediment management practice by establishing best practice expectations, sharing that information widely and removing roadblocks so that people can take action.

- Review forestry impacts on sedimentation, collaborating with the sector so that improved practices can be adopted sector-wide.

- Protect highly erodible soils through planting or avoiding development to keep the soil in areas where it is likely to run off.

- Address sediment in the coastal marine area by coming up with innovative and novel ways to reduce sediment so that habitats can be re-established.

The strength of this approach is that it recognises the multifaceted causes of accelerated sedimentation and the need for a range of solutions – both active and passive.

The plan also outlined specific actions related to fish stocks. Some selected actions are listed here:

- Transition away from using commercial fishing methods that impact benthic habitat in the Gulf.

- Undertake fish stock reviews: identify priority species and develop a schedule.

- Initiate an urgent review of rock lobster stocks.

- Implement a package of management measures aimed at reducing the density of kina/sea urchins[2] and restoring healthy kelp forests.

- Implement measures aimed at restoring abundant hāpuku/hapuka/groper[3]

- Undertake an urgent review of purse seining.

- Improve fisheries information and compliance through reporting and observer coverage.

Implementing recommendations within the plan has taken time, highlighting that the disconnect between recognising environmental problems and the systematic implementation of solutions to these problems is a major hurdle. Concerns have been raised about the lack of action,[4] and activities relating to the plan are progressing. Waikato Regional Council and Auckland Council responded to the plan and have implemented workplans following its release. The Government appointed a Ministerial Advisory Committee to help shape their response to the conservation and fisheries related proposals in the Spatial Plan.

The disconnect between recognising environmental problems and the systematic implementation of solutions to these problems is a major hurdle.

Initiatives that align with the plan have also gained traction, with the Department of Conservation and Fisheries New Zealand partnering with The Nature Conservancy to fund a shellfish bed and mussel reef restoration project in the Gulf.