Ideas for a more sustainable future – embracing innovation

The development of plastics and all plastic products is born from innovative thinking and design. Our urgent need to rethink plastics provides an environment for more boundary-pushing ideas. New ideas and innovative thinking are needed across the whole system of how we use and dispose of plastic. Many of these ideas exist already and need to be accepted, scaled to context and location and implemented as part of complex changing social systems.

The challenge to use plastic sustainably is ripe with opportunities for innovation. But the nature of innovation is not linear. Many breakthroughs and game-changing ideas come from left field and arise in response to a new need. To achieve the goals of rethinking plastics, we can construct a system that enables an innovative environment – one that doesn’t prescribe the solutions people come up with, but instead is receptive to new ideas. The research and innovation system can then nurture game-changing ideas and support scale-up of those that are proving to be successful.

Plastics are so ubiquitous in our lives and the issues posed by them are now so large that a single innovation, or even a single type of innovation, will not solve the challenge. There is no silver bullet. New materials and new machines, new recycling techniques, new uses for recycled materials, new business models, and perhaps most importantly, citizens who are ready to form a new relationship with plastics are all needed.

Plastics are so ubiquitous in our lives and the issues posed by them are now so large that a single innovation, or even a single type of innovation, will not solve the challenge

The development and adoption of new technologies can be a long, slow business. If we are to meet our aspirations to reduce our use of plastics and keep the plastics we use in circulation, we cannot wait for technological fixes to be developed – the key will be maximising the technologies we have already and encouraging fast adoption of new ways of thinking and new behaviours, as individuals, communities, businesses and government. It will also be important to ensure that pathways to later ideas that might provide better answers than the ones we can see today are not inhibited by rushing to quick solutions. For example, it would be disadvantageous to invest in recycling infrastructure for a particular type of plastic if a more sustainable alternative that is not compatible with this technology is just around the corner.

Innovation that supports the system-wide transformative change needed in how we use and dispose of plastics will be ongoing. In this chapter, we present a snapshot of ideas and innovations based on the principles of the 6Rs that can be adopted now or in the future. Supporting continued innovative thinking, sharing of ideas and supporting scale-up of the most successful concepts in this space will be key to making these examples of best practice, standard practice.

The 6Rs guide our ideas and innovations for rethinking plastics.

Rethink

Many of the issues raised by plastics are not caused by the properties of the plastics themselves but by the way we design, use and dispose of them. As a contrast, gold is as persistent in the environment as plastics but its initial cost and recycled value are strong incentives for it not to accumulate in landfill. If packaging were made of gold, we would not have a recycling problem![1] Plastic on the other hand is seen as disposable and part of our ‘throw away’ culture. Plastic products and packaging materials tend to be designed around cost, convenience and appearance, without consideration of end-of-life options. Even when issues such as biodegradability, recyclability and other options are considered, decisions are often made for functional and marketing reasons without a solid evidence-base for their overall impact on the environment. Rethinking and redesigning plastics requires a whole-of-life accounting approach to better account for the environmental costs of plastic and not just the cost of putting a product on the market. Product stewardship schemes are one way to begin this.

Factoring in the whole-of-life costs of a product will likely lead to a more sustainable result. Products can be designed in a way that extends their use, improves their recyclability in the local context, or reduces the chance of contributing to environmental leakage. Manufacturers currently seeking sustainable solutions struggle to navigate complex issues with no clear guidance from government. How aligned new design is to the future plastics economy of Aotearoa New Zealand will be limited by the support given to businesses by government and the degree to which good practice can be shared and scaled. Ideas that could form part of a system-wide rethink in how we use plastic are listed in the table below.

An example of a collection bin for compostable plastics to take them to an industrial compostable facility at Wellington Airport.

Ideas and innovations that can help us rethink plastics in Aotearoa New Zealand

| Idea | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guidelines and a code of practice for industry | Industry/ Government partnership, to be followed by business | WRAP APCO PREP tool Packaging NZ’s code of practice Danish circular plastic packaging manual UK circular economy standards | Can support a reduction in use of problematic plastic or packaging designs Businesses that have been waiting to see government direction before investing in change can do so Helps businesses consider life cycle of material (e.g. only use compostable packaging if collection systems) | Exported packaging needs to meet specific country’s requirements Immature infrastructure so difficult to deal with all plastics that businesses will be directed to use onshore Many products used and disposed onshore are imported | Develop clear guidelines for polymer, additive and colour use, and when to use single-use, compostable and reusable packaging Signal the direction of infrastructure development and timelines on any polymer bans to industry |

| Sustainable product design so all resources stay in the economy (see here for designing out plastic and here for sustainable materials) | Brand owners/ manufacturers | EMF published a series of case studies demonstrating circular design | Designing for longevity, remanufacture, or material recovery can reduce waste Use of LCA supports evidence-informed product design and factors in full life cycle environmental costs | Lack of incentive to change current practice Limited funding aimed at innovation to rethink plastics Cost of LCA studies prohibitive for some businesses and most are commercially sensitive | Expand waste levy to disincentivise waste Mandate product stewardship Support access to LCA info for businesses Funding and environment that enables innovation |

| New business models based on leasing vs ownership and the ‘sharing’ economy | Industry | Again Again coffee cups | Reduces waste by increasing the reuse of products Supports a change in practice around the need for ownership | High upfront cost for inventory for such business models | Funding and environment that enables innovation |

| Circular system redesign through collaboration, use of AI and/or big data and blockchain | Multiple businesses/ industries | XLabs: a circular economy lab for businesses in Auckland Coreo circular experiment Google Impact Challenge supporting initiative such as Gringgo SAP’s Plastics Cloud Circularise | More likely to find resource or use a waste product if more businesses involved Big data can support industrial symbiotic processing (wastes or by-products of one industry or process becoming raw materials for another) where it is difficult to determine manually[2] | Fragmentation – particularly with small businesses who struggle to reach economies of scale Challenges of complex global supply chains, cross-border trade of products, e-commerce and recycling [3] Access to AI, blockchain, and available data | Run a pilot project for a shopping strip or town Technological developments enabling effective small scale distributed approaches Connect businesses to repurpose waste streams as a resource or share logistics – could model off Industrial Symbiosis MBIE programme run by Scion for biorefineries R&D to support digital tools guiding circular transition |

Refuse

One of the simplest ways to lower the amount of plastic in the environment is to not use it in the first place. Refusing certain types of plastic would also help to support infrastructure by funnelling economies of scale, which will benefit collection, sorting, processing, reuse and recycling options. We discussed how individuals can change their habits to refuse unnecessary use of plastics and outlined some actions businesses can take to support transformative change in how we use plastic, including some local examples, in the ‘Changing our relationship with plastics’ section. In the table below we highlight innovative approaches that can reduce the overall amount of plastic entering the market.

Ethique is an Aotearoa New Zealand company that produces concentrated, plastic-free cosmetic products.

Ideas and innovations that support refusing plastics in Aotearoa New Zealand

| Idea | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ban certain single-use plastic products and types of plastic for certain applications | Government | Banned single-use plastic shopping bags (read the case study 'Is banning single-use plastic bags the right choice?') Bans as of 2018 detailed in UN report The EU and Canada banning single-use products and types of plastic for food and beverage packaging by 2021 EMF recommend limiting PVC (#3), EPS (#6) + labels for packaging | Removes the plastics that cause the most harm, supporting more sustainable plastic use Will drive innovation to replace these materials | Slow and still requires other system changes Need to give business plenty of time to redevelop packaging where necessary | Implement bans alongside other changes, e.g. product stewardship with incentives that drive the use of preferred plastics, a targeted tax on problematic materials and/or subsidy for approved materials |

| Concentrated and compressed products that eliminate plastic packaging | Brands | Ethique beauty bars Dishwashing tablets Toothpaste tablets Edible sachets TrioCup | In some cases, removes plastic use altogether May reduce transport emissions | Can take a significant investment to develop Need to compete against well-established products with a foothold in market Need to ensure product isn’t more environmentally problematic than what it is replacing | Support for R&D for innovations that reduce or remove plastics Brands can connect with retailers who want to provide customers with sustainable options Perform LCA studies to compare new product or packaging against current alternative |

Reduce

By 2050, plastics manufacturing and processing may account for as much as 20% of petroleum consumed globally and 15% of the annual carbon emissions budget. However, it is important to remember that while plastic is itself a contributor to carbon emissions, it also helps to reduce emissions by offering a lightweight alternative to materials such as metal and glass. In order to retain the benefits of plastic and balance these against a need to reduce fossil-fuel consumption, innovation is required to reduce the amount of plastic we use and shift to using bio-based and/or recycled plastic where possible. Manufacturers and polymer scientists can work to reduce the amount of plastic used in certain applications. In the table below we highlight ideas that may help to reduce the amount of plastic used.

Ideas and innovations to reduce the amount of plastic used in Aotearoa New Zealand

| Idea | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light-weighting materials | Plastics industry | DuPont developed thermoplastics to replace metal and plastic car components Nestlé reduced weight of water bottles by 22% | Product fulfils same purpose Reduces emissions | Can reduce the effectiveness of mechanical recycling Some sorters at MRFs cannot detect plastics if too light Can take a significant investment even for small reduction for brand Manufacturers may not have infrastructure needed | Support innovation or R&D across businesses that benefits all Collaboration between businesses and researchers Equip NZ manufacturing industry with necessary processing equipment Equip recycling industry with infrastructure adapt to lighter bottles In silico testing |

| Changing product to reduce required plastic packaging | Brands | Unilever made a laundry liquid 6x more concentrated and reduced plastic volume by 72% | Material cost savings Reduced emissions from transport | Cost of R&D to change product may prevent brands doing this May depend on a willingness of consumers to change a practice | Regulate to ensure whole-of-life costing via product stewardship of products to drive business to reduce use of packaging |

Reuse

There has been a significant amount of innovation for reuse systems in recent years. We shared some local examples of businesses facilitating reuse or establishing new business models based on reuse systems in the ‘Changing our relationship with plastics’ section. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) published a detailed report on reusable packaging, which includes examples of innovative reuse systems. In the report, EMF describe four reuse system models for business to consumer packaging: the user refills at home, refills on the go, or returns the packaging from home or on the go. Different systems are needed for non-packaging industries and business to business (B2B) packaging or products. In the table below, we highlight ideas to support reuse of plastics.

Ideas and innovations to support reuse of plastics in Aotearoa New Zealand

| Idea | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reusable systems to replace single-use products or packaging | Businesses | EMF shares 69 examples, including Globelet – a local company (read the case study 'A reusable system to replace single-use cups') | Cuts costs Builds brand loyalty Improves user experience Gathers intelligence Optimises operations Adaptable to individual needs | Difficulty reaching economies of scale Competing against convenience of buying new single-use product | Adapt global ideas to local system Establish reward schemes to drive uptake Education for businesses and retailers |

| Logistics innovation in supply chains for reusable secondary and tertiary packaging | Industry | CHEP provides reusable options to reduce single-use plastics in logistics (read the case study 'Reuse systems in global supply chains') Foodcap | Benefits all parties in the supply chain | Small population and large geographical distances present particular challenges | Ensure solutions are designed for NZ |

| Product libraries | Community groups/ councils | Toy libraries across NZ Tool libraries | Changes ideas about need for ownership Reduces waste by keeping product in circulation | Resource to get up and running Profitability or reliance on volunteers | Partner with businesses or organisations to give second-life to old equipment |

| Logistics innovation to keep products in circulation (e.g. toys) | Business | Lego is piloting a free return system for unwanted bricks to be given to children in need | Easy for people to return Reduces waste to landfill | Distance from manufacturers or brands if multinational may make logistics difficult | Connect systems with Australia Develop local solutions for unwanted toys – e.g. give to toy libraries |

| Sterilisation of single-use products for reuse | Medical industry | Medsalv reprocess single-use medical devices | Cost savings Reduction of waste to landfill Tracked process for safety and quality assurance | Most hospital’s sterile service departments do not have access to equipment for cleaning intended single-use products | Support scale-up of organisations like MedSalv who have this equipment |

| Refill stations and services | Businesses/ community groups/ Government | RefillNZ (water) Ecostore refill stations | Provides system for people to reuse bottles, reducing overall plastic use May prevent litter | Resourcing required for public stations for water Competing against convenience of buying new single-use product | Prioritise resource here to reduce spend required to clean up the environment later Incorporate cost of packaging into product cost to balance against convenience |

| Repair and reuse businesses or organisations | Businesses, community groups, local councils | Op-shops Secondhand shops Community reuse centres Repair cafes | Can give a wide range of products a second life Can provide funds to community groups | Competing against new products May rely on volunteers | Partnerships between community groups and councils Embed within other organisations |

Recycle

Recycling is not the only solution to our plastic problem, but it does have an important place in rethinking plastics. Without high-quality recycling streams there is no economic viability in recycling plastic due to limited market pull-through. Without a functional recycling market, the current environmental issues we face related to plastic use and waste will be ongoing. Addressing issues related to the quality of plastic that enters and leaves the recycling stream will help to establish a more stable onshore recycling market, which in turn can reduce demand for virgin plastic and reduce plastic waste to landfill.

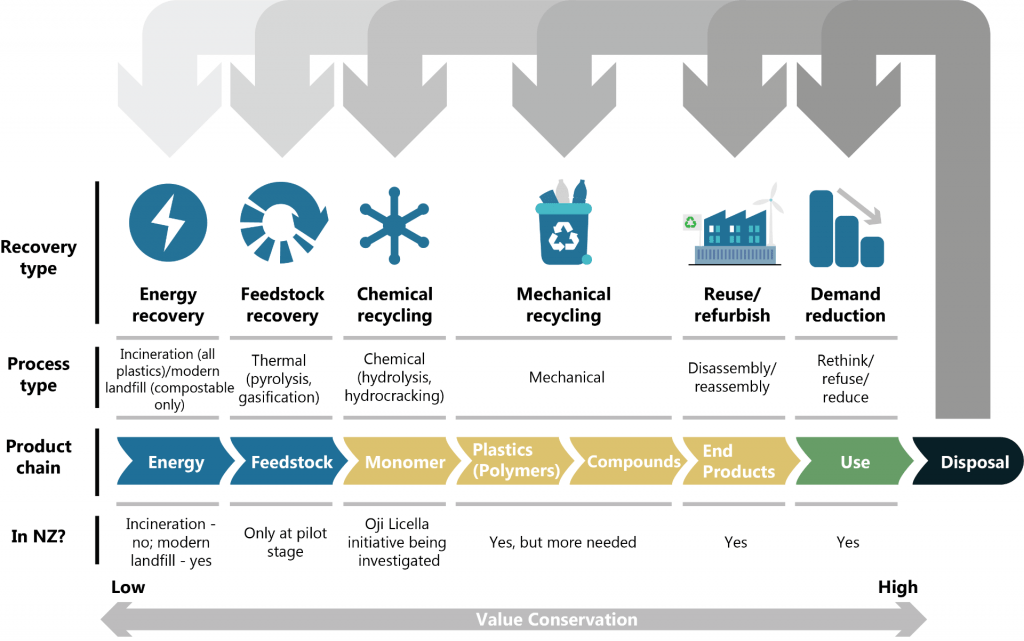

The type of plastic ultimately dictates which (if any) method of recycling technology can be used to keep the material in circulation. In practice, product design, collection and sorting methods, and individual behaviours also determine whether a product is recycled. Traditionally we have relied on mechanical recycling techniques to keep plastic in circulation. These methods have proven to be ineffective for the majority of plastics, with estimates that globally only 9% of all plastic ever produced has been recycled. In addition to innovative products, business models and materials, we can look to ways to improve current recycling practices, so that we can get the most out of the plastic materials used. We can also consider whether there is a place in Aotearoa New Zealand’s new plastics economy for new processes that keep materials in circulation, such as chemical and monomer recycling, and feedstock and energy recovery.

Different recovery techniques available. Adapted from Denmark’s New Plastics Economy, McKinsey and Company.

In their detailed overview of the state of Aotearoa New Zealand’s recycling sector in late 2018, the National Resource Recovery Taskforce (NRRT) highlighted that there are issues across the whole value chain of the current recycling system that need to be addressed in order for recycling to be a feasible solution for those plastic products that cannot be eliminated or reused. As this was in response to China National Sword, the recommendations were mainly focused on packaging applications of plastics.

Taskforce recommendations from the NRRT that were accepted by the Ministry for the Environment include:

- Identifying the gaps in materials recovery and waste infrastructure where investment is needed

- Reviewing kerbside collection and processing systems to identify how to increase the quality of recyclables and to ensure more materials can be recovered and recycled instead of going to landfill

- Undertaking feasibility studies around how to increase Aotearoa New Zealand’s fibre (paper and cardboard) processing and plastic reprocessing capacity

- Examining how product stewardship for packaging can be used to ensure manufacturers consider what happens to packaging once a product is used by the consumer

- Assessing the options for shifting away from low value and difficult-to-recycle plastics, such as single-use plastic bags and other low volume and/or mixed materials. This could include regulations around ensuring plastic packaging is able to be recycled and/or to require a portion of recycled content in packaging

- Running an education campaign to help New Zealanders ‘recycle right’, and reduce the amount of recyclable materials going to landfill because of contamination

- Developing model contracts for the sector to reduce contamination, increase transparency and to better accommodate fluctuations in market prices for recyclable materials

- Developing a sustainable procurement plan and guidelines to encourage purchase of products made of recovered and recycled materials.

Here we build on the NRRT’s recommendations by outlining improvements and innovations that could be implemented across the whole recycling value chain to address current issues and improve rates of recycling.

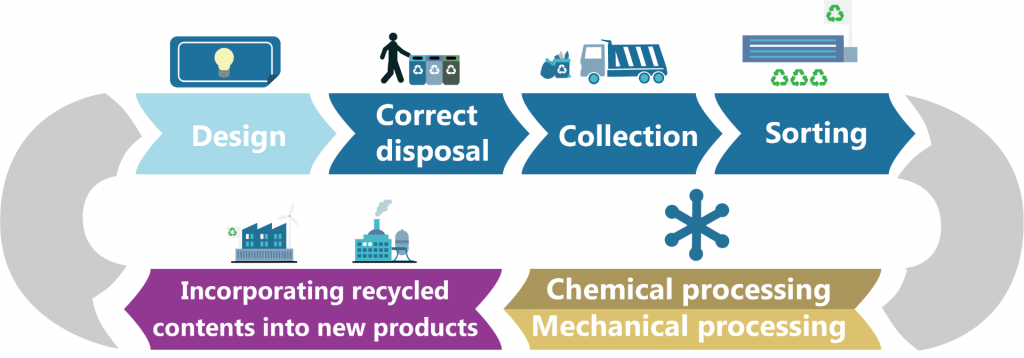

Areas where new systems and innovations could improve recycling.

Design for recyclability

If recycling is the desired end-of-life outcome for a product, it should be designed to ensure that it can and will be recycled in the local context. Figure 31 illustrates the types of materials that are easy (commonly collected), possible (collected in some places), and difficult-to-recycle (collected in no or few places) in the kerbside recycling systems across Aotearoa New Zealand. The value of the recycled content affects whether it is practically recycled because whether there is a market for the materials drives whether a council collects it. With current infrastructure, recycling markets and reliance on sending a significant proportion of recycling offshore, clear PET (#1) and natural HDPE (#2) have the highest recycling value; coloured PET (#1), coloured HDPE (#3), LDPE (#4) and PP (#5) are recyclable but likely to end up in a ‘mixed plastics’ recycling stream with low value, PVC (#3), PS (#6) also end up in a ‘mixed plastic’ stream in low quantities so it is difficult to find a market, and ‘other’ types of plastic will not be recycled and will likely contaminate other recycling streams.

Other factors aside from material choice can impact recyclability, including colour, the size of the product, the size and material of the label, and electronic tracking systems and sensors. It will also depend on whether the product is used in the household and therefore enters the kerbside recycling stream, or if it is used in a commercial setting. For example, PVC (#3) packaging is unlikely to be recycled but PVC (#3) pipes could be through various commercial recycling streams that exist locally. Best-practice guidance for businesses that includes information on how to design their products to improve recyclability is needed. Some examples of best practice that would improve recyclability through design changes are outlined in the table below.

Left: Though plastics 1-6 are all technically recyclable, the volume and market for the recycled content dictates whether councils accept these across the country. Credit: royalsociety.org.nz/plastics licenced under CC BY 3.0 NZ.

Ideas and innovations for improving the recyclability of products in Aotearoa New Zealand

| Idea | Why | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avoid using coloured PET (#1), PS (#6), PVC (#3) and rigid PLA (#7). Switch to clear PET (#1), natural HDPE (#2) and PP (#5) | Onshore processing exists for clear PET (#1), natural HDPE (#2) and PP (#5) Good markets for these plastics Reduces contamination of PET (#1) recycling stream by rigid PLA (#7), PS (#6) and PVC (#3) Material able to go through multiple rounds of recycling Colour can change the flow properties of the plastic, making it less predictable in certain processes Blending different coloured plastics turns an ‘icky’ brown or grey colour with low or no value | Currently the cost of alternatives is cheaper Coloured packaging may be part of brand properties | Whole-of-life costs factored into PSS or CDS to drive use of recyclable material Industry-wide acceptance for level playing field |

| Avoid using multiple materials where they are not easily separable | Monomaterial-based products are more easily recyclable | Some products require multiple different materials because each material achieves a particular function | Clear labelling system that shows what part of product is recyclable Design for disassembly by consumers Research into multilayer materials where each layer has different physical properties but same chemical composition |

| Label size under 60% | Optical sorters need at least 40% of the packaging to be visible to detect type of plastic | Brand willingness Size needed for mandated information Want to include recycling labelling as well with limited space | Digital barcodes for more labelling information online New sorting tech |

| Using different packaging material if product is hard to wash off plastic | Residual contamination renders the material unrecyclable | Use of glass (which is easier to wash) increases weight which can increase transport emissions | LCA studies to understand life cycle impacts to guide choices |

Ease and understanding of how to recycle

To maximise opportunities for resource recovery and reuse at end-of-life, we first need to ensure that all types of plastics can be identified at end-of-life and disposed of correctly. If a plastic product can be recycled or composted, it needs to end up in the appropriate recovery system. If a plastic product can only be composted in a commercial composting facility, it must not end up contaminating the recycling stream or a domestic compost heap where it will not decompose. The complexities around how plastics are categorised are covered in the subsection ‘The current state of plastics in Aoteaora‘. This complexity has led to general confusion in the public around the currently relied on resin ID codes and recycling symbols.

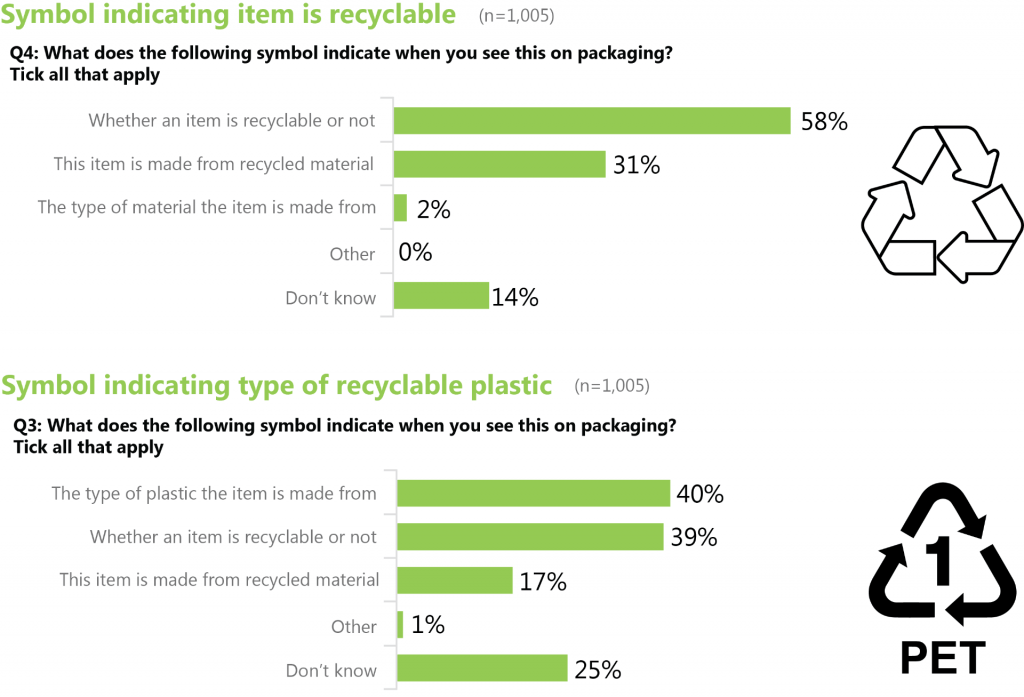

WasteMINZ survey responses illustrate high levels of misunderstanding for the existing recycling and resin ID codes that are used on plastic packaging. All respondents (n=1005).

At the time of publication, there were no national standards on how to categorise or label plastics in Aotearoa New Zealand. Current approaches rely on voluntary uptake and are limited in their application and effectiveness (outlined in Appendix 3). We need clearer language and symbols for plastics, including a simple recycling label that tells people whether to recycle or dispose of a product. This will improve the efficacy of recycling streams by reducing contamination of recycling streams with non-recyclable plastics (sometimes due to ‘wish cycling’ – where people place non-recyclable products in the recycling bin in the hope that they will be recycled), and reducing the amount of recyclable plastics ending up in landfill. There is also need for better public understanding about how to recycle correctly and the life cycle impacts of various packaging choices. Using standard nomenclature and having clear labelling that is easy to find and read is key to facilitating best practice, particularly in the household setting for kerbside recycling and refuse. Wide adoption and public understanding is critical for success, and implementation of labelling schemes should be done in conjunction with public education initiatives. In the table below, we highlight ideas and innovations that may be useful to help improve public understanding about plastics and help people dispose of waste correctly.

Ideas and innovations to improve recycling efficacy through improved public understanding

| Idea | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public education | Government | Improve the quality of the materials entering the recycling stream | Current fragmentation between systems at different councils | Standardise recycling systems among NZ Councils | |

| Physical labelling | Brand owners to apply (voluntary or regulated by Government) | Australasian Recycling Label (read the case study 'The Australasian Recycling Label') UK on-pack recycling label (OPRL) Thumbs Up New Zealand proposed system | Ready to go Can be applied to all products Doesn’t rely on resin ID which is widely misunderstood If consistent with international practice may be better understood by some tourists | Regional variation in kerbside recycling Use of adhesives and different plastics for the label may contaminate recycling stream | Standardise national collection Have a standard recycling label Compliance costs may be prohibitive for small brands |

| Digital labelling for online shopping | Retailers | Crunch and Flourish digital packaging star | Easily adaptable to different contexts Easy to update Can build on physical labelling schemes such as the ARL | More accessible via online stores, can be delivered in-store via technology and loyalty programmes Small-scale consumer testing of Packaging Star to date | Upgrade to digital price labels in store Online trial with a retailer to assess shopper behaviour |

Collection

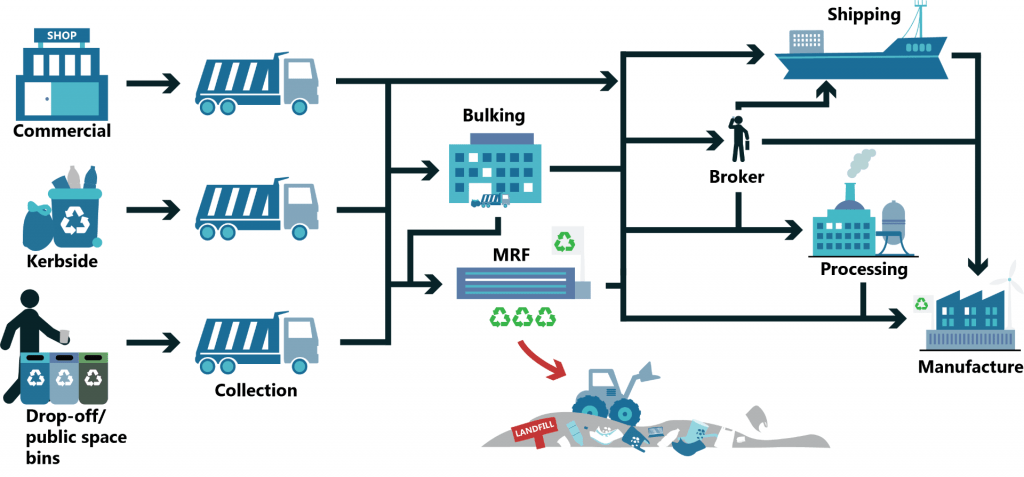

How waste is collected impacts the rates of recycling.[4] Currently in Aotearoa New Zealand, plastic is collected for recycling through household kerbside collection, public space bins, drop-off points (common in rural areas) – these are typically rate-payer funded. Other plastic is collected for recycled through commercial collections. For household kerbside recycling, public space bins and drop-off points, plastic is sent to a material recovery facility (MRF) where it is sorted prior to being shipped offshore for recycling or sent to one of Aotearoa New Zealand’s few onshore recycling facilities (read the case study ‘Developing onshore closed-loop mechanical recycling solutions’). Commercial plastic material is sometimes sent directly offshore for recycling, without need for sorting at a MRF, or is reprocessed in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The current process for plastic recycling in Aotearoa New Zealand. Figure adapted from Eunomia Consulting.

The specific types and presentation of plastic that are accepted through kerbside collection differ by council – for example, some councils request bottle lids left on while others want them removed. Improving, standardising and expanding collection systems is necessary to increase rates of recycling. Collection points need to be easily accessible nationwide and facilitate the highest quality recycling streams. Consistency should be balanced against the needs of different regions. In the table below, we highlight ideas and innovations that may be useful to help improve collection systems to improve recycling.

Ideas and innovations to improve recycling efficacy in Aotearoa New Zealand through improved collection

| Idea | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardise nationwide collection and methods for household kerbside recycling (highlighted in NRRT) | Central and local government | WRAP UK developed a framework for greater consistency in household recycling | Reduces confusion around recycling practices Allows national education campaign with shared messaging | Cost barriers to align different systems falls on local government NZ’s different regions may require different systems Restrictions from existing contracts and infrastructure | Support from central government to standardise Have 2-3 variations on a common system |

| Separate organic and inorganic waste | Local government | Stewart Island, Timaru District Council, Christchurch City Council Recology (San Francisco) | Keep plastics less contaminated Opportunities to compost food waste | Councils tied into existing contracts Carbon footprint of separate collection system may outweigh benefits Availability of green waste | Undertake an analysis to compare carbon footprint of organic waste collection vs methane collection from landfill to guide decisions |

| Container deposit scheme (CDS) | Central and local government | Work underway to design a scheme for NZ Various states in Australia, US, and jurisdictions in EU Norwegian system (read the case study 'A 97% recycling rate through a container deposit scheme') | Packaging recognised as a valuable resource Drives higher rates of recycling and generates higher quality recyclate Options for deposit exchange (cash, co-benefits e.g. transport tickets, digital tokens) Litter reduction Potential social and community benefits through fundraising, enterprise etc. | Upfront costs to implement Accessibility in regions and remote areas Adequate transition time | Implement tax for industry to support this Engage with government counterparts in places with experience in CDS (e.g. states in Australia) to understand the process to implementation and lessons learned Clearly signal implementation date well in advance to business to allow adequate transition and enable effective implementation |

| Product stewardship schemes (PSS) (can be voluntary, accredited or mandatory) | Government | Work underway to regulate product stewardship for some materials/ products Agrecovery Plasback Car bumpers Public place recycling scheme Child car seats PVC (#3) pipes, e.g. SULO and Marley | Strong support for this Places value on material to be returned to system Improves quality of recycling stream Prevents hazardous streams being disposed of inappropriately Cost incorporated into upfront purchase so no extra cost at end-of-life to manage/ recover materials correctly | Difficulty designing an effective scheme that can be equitably accessed in different regions | Make mandatory or accredit Co-design scheme with industry, with variations to meet local needs Learn from international examples |

| Store drop-off programme for plastics not collected in kerbside collection | Industry | Soft Plastic Recycling Scheme | Prevents plastics going to landfill Provides source-separation | Schemes that rely on customers to return packaging to a separate destination may not match other collection methods End markets required Need a coordinated approach across stores Providing soft plastic and compostable packaging collections at the same collection points may result in contamination | Stores who sell products offer to collect back Ensure wide and accessible distribution |

| Store drop-off for compostable plastics | Industry | We Compost are trying to do this | Mono-material streams of high quality and reduced risk of contamination of recycling streams Waste stream goes to correct infrastructure | Lack of commercial composters willing to take compostable plastics Schemes that rely on customers to return packaging to a separate destination may not match other collection methods Providing soft plastic and compostable packaging collections at the same collection points may result in contamination | Encourage brands to only use industrial compostable plastics if they have an end market for composting these Ensure wide and accessible distribution |

| Blockchain to support action through PSS, extended producer responsibility, community recycling | Industry/ community | Empower The Plastic Bank Litterati | Enhances business model innovation Recycling for digital payment | Lack of a coordinated approach | Policy and strategy to support new business models and community initiatives |

Sorting

Sorting can happen at source and/or at the MRF, where plastic is separated out from other materials that are collected (glass, paper, cardboard) and also separated into different types of plastic. The technology at the MRF determines which types of plastic can be separated out. Some MRFs have manual sorting by pepople and others have fully automated systems. In general, plastics are separated into bales of clear PET (#1), natural HDPE (#2) and mixed bales of plastics #3-7 and coloured PET (#1) and HDPE (#2). Contaminated plastics and plastics that are not accepted at the particular MRF are removed and sent to landfill.

Systems that are more effective at sorting plastics into individual material streams will improve the recycling system by increasing the quality (and therefore the value) of the recycled content. The ultimate goal for a circular economy is that the quality of the recycled plastic means it can be used for the same product to close the materials loop. A study assessing the potential for different recovery systems in Europe to close the materials loops confirmed that higher source‐separation and MRF efficiencies lead to higher recovery.[5] With current technology and raw material demands, less than 42% of the plastic loop can be closed. The potential to recycle materials is high, but factoring in the quality threshold to recover to the same quality of plastic, at best 55% of the generated plastic was suitable for recycling due to contamination. The study concluded that source‐separation, a high number of different materials streams, and efficient MRF recovery were critical to close the materials loop. A study of the Dutch recycling system also identified a clear quantity-quality trade off, with a rise in the amount of plastic packaging collected for recycling leading to a larger amount of waste at sorting facilities.[6] The study highlighted the need to focus on the quality of materials received for recycling, not just increasing volumes, to close the loop on plastics.

The study concluded that source‐separation, a high number of different materials streams, and efficient MRF recovery were critical to close the materials loop

In the table below, we highlight ideas and innovations that may be useful to help improve sorting processes to close the materials loop.

Ideas and innovations to improve recycling efficacy through improved sorting processes

| Idea | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerbside sort (rather than comingled) | Local government | Christchurch, Great Barrier Island | Keep plastics less contaminated May require less upfront investment | Inefficient H&S implications Cost to councils and existing contracts Environmental leakages | Public education to maximise sorting at source Best H&S practices from overseas sorting at source collection |

| Manual sorting at MRF | Local government/ industry | Zero Waste Raglan | Requires less upfront investment | Inefficient Finding market for sorted material, particularly smaller volumes | Resourcing issue Coordinate with other councils for economies of scale |

| Optical sorting | Industry | Used in some MRFs e.g. VISY in Auckland | Efficiency Accuracy | Cost-prohibitive for smaller facilities because of upfront investment Cost-prohibitive for larger facilities because of requirements for processing higher volumes Can’t detect all plastics, e.g. black pigment | Support to meet upfront costs for regions Strategically invest in infrastructure around the country Design downscaled systems for smaller throughput so sorting can be done locally in regional areas Advanced tech, e.g. Unilever developed detectable black pigment so black plastics can be recycled |

| Secondary MRF (i.e. a second MRF for sorting into mono-material streams) | Industry (supported by government) | Titus MRF in the US is piloting this approach | Can achieve more mono-material streams Helps overcome NZ’s issue of economies of scale for plastics in mixed plastic stream | Logistics needed to transport mixed plastics to another location (plus associated emissions from transport) Small population size may still limit economics of recycling the plastics in the mixed plastics stream | Undertake feasibility studies to determine viability of secondary MRF approach Establish plant(s) in strategic locations to be most cost-effective and minimise transport-related emissions |

| Marker technology/ methods for traceability of plastics | Manufacturers/ brands/ MRFs | UV tracked digital watermarks | Requires fewer changes to packaging materials and labelling for brands | Requires wide acceptance across industry to be effective Cost-prohibitive | Develop international standards for new recycling methods |

| Use of AI and robotics for improved sorting | MRFs/ consumers | Alchemy SureSort Liam the apple recycling robot Zen Robotics Trashbot Bin-e Samurai | Faster, more accurate and cost-efficient sorting Potential to connect to plastic recycling value chain Small-scale operations possible | Government investment in R&D is limited Cost to implement in public infrastructure | Create an R&D investment/science challenge investment strategy around AI/Robotics and plastic waste management |

| Laser-assisted sorting | MRFs | Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy | Efficient May allow for bioplastics to be collected in kerbside recycling because of ability to discriminate[7] | Cost to implement in public infrastructure Cost-prohibitive for smaller commercial operations | Strategic investment in infrastructure across country |

Mechanical recycling

Mechanical reprocessing is an effective recycling method for certain types of plastic where the chemistry allows melting and reforming into new products, but it faces challenges in the current context due to there being different sources of plastic of varying quality, different types of plastic (not always identifiable) and high levels of contamination. Having higher-quality mono-material streams will naturally improve recycling markets.

Pre-consumer or industrial plastic waste tends to be more recyclable than post-consumer plastic waste (e.g. kerbside collections) because it is cleaner and not mixed up with other types. Specific types of plastic that are widely used in a particular industry (e.g. construction) may benefit from coordinated approaches to recycling and more accessible information about which recyclers will take certain plastic streams. These already exist for some waste streams, such as for expanded polystyrene (EPS). In contrast, household waste faces greater hurdles to getting quality streams of plastic that can be mechanically recycled. For example, a commercial closed-loop system may be feasible for LDPE (#4) due to businesses having high volumes of a clean mono-material stream from secondary and tertiary packaging. In contrast, it may be less feasible to establish a closed-loop system for post-consumer LDPE (#4) (e.g. from kerbside collection) because there is not a large enough volume of clean, high-quality LDPE (#4) from this collection stream to make it economic.

Though in theory some pure plastics such as HDPE (#2) and PET (#1) are infinitely mechanically recyclable, in practice these will degrade over time.[8] However, intermixing recycled plastics with newer materials during each recycle keeps a viable pool of recycled plastic and in some markets PET (#1) has successfully been maintained in circulation for many years. In addition, additives have been developed to reduce degradation. Conversations between the panel and a variety of stakeholders suggest that with the current amounts of waste plastic and the available technology, it is only feasible to consider mechanical recycling as an option for post-consumer plastic waste for PET (#1), HDPE (#2) and PP (#5), and that infrastructure to be able to recycle these onshore is necessary. We already have more than enough capacity for closed-loop PET (#1) recycling (read the case study ‘Developing onshore closed-loop mechanical recycling solutions’). PET (#1) actually only accounts for around 7% of the virgin resin imported into the country. Other plastics with good recycling potential due to their chemical composition and end market are HDPE (#2) and PP (#5), which make up 26% and 18% of imported resin respectively. The focus should now be on investing in infrastructure, including sorting, to develop onshore closed-loop or durable solutions for HDPE (#2) and PP (#5).

The recycling process at Flight Plastics in Wellington. Credit: Flight Plastics.

We already have more than enough capacity for closed-loop PET (#1) recycling. The focus should therefore be on investing in infrastructure, including sorting, for closed-loop or durable solutions for HDPE (#2) and PP (#5)

Plastics NZ is working with local recyclers to develop an onshore solution for PP (#5) recycling. There are examples of closed-loop recycling for HDPE (#2), such as WILL&ABLE recycling New Zealand milk bottles into cleaning product packaging, but these require scaling. There are also a number of recyclers who currently recycle HDPE (#2) into durable products, but current infrastructure does not allow for closed-loop recycling for food grade materials or detergent grade materials. HDPE (#2) that is used in packaging for food and drinks has different requirements to HDPE (#2) used in cosmetics and detergents. For example, food-grade recycled content has to meet food-safety standards and the environmental stress crack resistance needed for detergent-grade HDPE (#2) is higher because of the longer use of the packaging. Keeping these streams separate may lead to higher yield closed-loop solutions for respective streams and should be considered when estimating material flows.

At present, there are some mechanical recycling solutions for soft plastics collected in the Soft Plastic Recycling Scheme that mix these materials with HDPE (#2) to form new products, such as fence posts. The soft plastics are the filler for these new materials – it is not a circular solution, but it could be argued this reprocessing gives these materials a longer life than through recycling as they are incorporated into durable products. Soft plastics require further onshore solutions, which may go beyond mechanical recycling. For example, there may be some applications where it is better to use compostable soft plastic packaging rather than relying on packaging being recycled.

Innovative approaches are needed to improve the quality of the materials that are mechanically recycled onshore. In the table below we outline technologies that may be able to improve the efficacy of mechanical reprocessing. Government can work with industry to establish new infrastructure onshore to process plastics, based on a shared action plan. Scion’s New Plastics Economy Roadmap project will develop this further.

Ideas and innovations to improve recycling rates through mechanical recycling

| Technology/idea | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wash-off adhesive | Brand owners | RW85C for PET (#1) containers | Can undergo common PET (#1) recycling processes without contaminating the recycling stream | Cost Practicality of wash-off adhesive in humid and chilled environments where condensate is common | Financial incentives or regulation for all to use |

| New applications for mixed plastic recycling | Industry | Plazrok (read the case study 'Using mixed plastics in new materials') EcoGlobal FuturePost Building blocks (ByBlocks by ByFusion) Roads | Uses otherwise non-recyclable plastics, and reducing waste to landfill | Possible safety issues with potential leach or out-gas toxic additives, or leaching microplastics, depending on application and feedstock Not a closed material loop Requires a system or scheme for products to be recovered at end-of-life | Rigorous environmental testing and ongoing monitoring before application Expert peer review of technology before it can be used |

| Textile recycling | Recyclers | Econyl – Regenerated nylon from waste for fashion and interior industries Worn Again Technologies | Reduces landfill waste Provides economic opportunities for commercial and not-for-profit organisations | Cost Quality – aesthetics and functionality may be reduced through mechanical processing, difficult to reprocesses mixed fibre textiles | Financial incentives to develop infrastructure onshore R&D Design for remanufacture initiatives |

Chemical recycling

Several new chemical recycling technologies, some drawing on the principles of green chemistry, are emerging that address limitations in materials composition and mechanical recycling processes. Chemical recycling techniques may be able to keep previously unrecyclable plastics and lower-quality recyclable plastics in circulation. Some techniques can process mixed plastics and others can generate high-value recyclate from a material that would only generate low-value recyclate through mechanical recycling.

Chemical recycling techniques may be able to keep previously unrecyclable plastics and lower-quality recyclable plastics in circulation

Chemical recycling usually uses some combination of high temperatures, pressures, solvents and reagents to transform plastics into simple organic compounds, including the constituent monomers from which the polymers were made, small-chain hydrocarbons, and/or petrochemical feedstocks. Remaking the original polymer from the constituent monomers obtained this way is generally seen as a particularly circular method because it enables the same grade and type of polymer as the original to be formed from the waste plastic material, albeit with less than 100% yield. The new polymers formed this way are usually indistinguishable from the virgin polymers and can be used for food applications, which could help to address some of the food-safety concerns associated with using recycled plastic from mechanical recycling. The related process of conversion converts plastics into fuels or petrochemical feedstock that can be fed into refineries or chemical plants, respectively.

Because chemical recycling can create high-quality recycled plastic and maintain value for the material that may be lost if mechanically recycled, it will be necessary to increase overall rates of recycling and fill the strong demand for recycled resin, which cannot currently be met with existing mechanical infrastructure and technology (read the case study ‘A model to sort a whole country’s plastic waste’). This strong demand is illustrated by Loop, a Canadian PET (#1) chemical recycling start-up, and Indorama, the world’s largest PET (#1) manufacturer, roughly doubling the capacity of their first PET (#1) chemical recycling facility because capacity was fully subscribed by customers, who include Danone, PepsiCo and Coca-Cola.

There are currently no chemical recycling facilities in Aotearoa New Zealand. Oji Fibre Solutions has publicly stated they are working with iQ Renew and Licella to investigate an onshore chemical recycling solution using the Cat-HTR™ technology, which they cite is ready to move from the pilot phase to commercial roll-out. This catalytic hydrothermal reactor technology uses water at near super-critical temperatures to reverse chemical bonds not possible at lower temperatures. Additional investigations into onshore chemical recycling options are underway but not public. In the table below, we highlight the chemical recycling technologies that may be applicable to close the loop on materials.

Zero Waste Europe recently published a report outlining the state-of-play and policy challenges related to chemical recycling. The report describes pilot plants for different techniques and highlights that only limited information about the environmental performance of chemical recycling technologies as a whole is available and further research is required, especially for techniques that use organic solvents. Chemical recycling is an active area of research. For example, the US National Science Foundation has ‘Engineering the Elimination of End-of-Life Plastics’ as a topic for their Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation (EFRI) program for 2020.

The conclusions drawn in the Zero Waste Europe report that are also valid for the Aotearoa New Zealand context are:

- If closing the materials loop is the focus of Aotearoa New Zealand’s future plastic system, regulation will be required to ensure that chemical recycling technologies are used to do this rather than create energy or fuel

- Excessive emphasis on chemical recycling as a solution to the current issues with the plastics economy risks encouraging the status quo with plastic use and could undermine efforts to shift approaches to plastic use up the waste hierarchy

- Chemical recycling is not a ‘now’ solution at an industrial scale. Most plants are only in pilot stage and industrial-scale roll-out is not expected until 2025 or later. Therefore, decisions around which technologies have a place in Aotearoa New Zealand’s future plastics system need to factor in the drive to reduce use of non-recyclable plastics by 2025

- If chemical recycling technologies are landed on as a solution, we need to ensure that these are aligned to the quantities and types of plastic that we expect from 2025 onwards. For example, coloured PET (#1) has low value as recycled plastic because it turns grey when different colours are mixed. Some chemical recycling techniques may be able to address this by removing the colour and creating virgin-quality, clear PET (#1), which has strong demand. But the need for technology to address coloured PET (#1) may be displaced by brands shifting to clear PET (#1), which is more likely to be recycled in the local content, prior to commercial-scale facilities being established

- Chemical recycling should be used to deal with degraded, coloured and contaminated plastics and never with high-quality plastics coming from separate collection.

Chemical recycling is not a ‘now’ solution at an industrial scale. Most plants are only in pilot stage and industrial-scale roll-out is not expected until 2025 or later

Ideas and innovations that use chemical recycling technologies

| Technology | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled thermal depolymerisation (pyrolysis) Processing back to monomers using high temperatures | Cat-HTR™ technology (catalytic hydrothermal reactors): Oji Fibre Solutions and iQ Renew looking at this for NZ Diagen (Solray Systems): Continuous hydrothermal conversion of biomass into liquid hydrocarbon fuels COMY Environmental NZ Ltd: Start-up with exclusive right to patent and technology from parent company in China (Zhejiang COMY Energy Tech). System can take plastic types 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7[9] Eneform in Christchurch plan to process tyres into oil and gas fuels from 2020, adding plastics later Renewology uses a pyrolysis technology to convert low-grade plastics into fuel and petrochemical feedstocks Enval (UK) has a process than can recycle plastic aluminium laminates | Most suitable for easily mechanically recycled plastics PET (#1) and PP (#5) and better with mono-material streams, but can take mixed plastics and plastics that are not easily mechanically recycled Decontaminates polymers Doesn’t face degradation issues Can be reprocessed to form new plastics if conditions are right, but more likely fuels and other hydrocarbon feedstocks | Needs sustained and consistent amount of feedstock May not be economically viable due to small population and large geographical distances with poor rail connectivity – requires scale but is costly Not 100% yield Requires regular maintenance Downtime is expensive May still require sorting and cleaning Plastic to fuel technology may not close materials loop Energy intensive process | Undertake economic analysis to determine viability for NZ Technological developments enabling effective small scale distributed approaches Regulate to ensure technology used to close materials loop Use for specific materials e.g. LDPE (#4) film |

| Gasification[10] Processing back to syngas (a mixture of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and hydrogen) | Sekisui Chemicals (Japan) | Can take mixed plastics and other waste | May not close materials loop Energy intensive | Local studies and trials to determine if suitable |

| Chemical depolymerisation Processing back to monomers or intermediates using chemicals | Existing pilot plants for PET (#1), PU, PA BP developing pilot plant in the US in 2020 for lower-value PET (#1) scrap | Decontaminates plastic and removes additives and colours Plastic can be processed infinitely and produces virgin-quality plastic Fewer issues around varied quality of input plastics Can be used for low quality and coloured plastics that are problematic for mechanical recycling | Cost – significantly more expensive than mechanical recycling Only works with monostreams (PET (#1), PU, PA, PLA, PC, PHA, PEF) and need to remove as much contamination as possible Don’t fully understand environmental and systemic impacts of this on yield, leftover by-products and chemical safety of catalysers that are sometimes needed for reaction | Further research needed around safety Local trials prior to scale-up |

| Solvent-based purification Uses solvents to process plastic back to polymers | PureCycle technologies | Results in high yields of recovered polymer Decontaminates plastic by removing additives and dyes and deals with residual contamination New plastics can be used for food packaging Can help recover polymer from multi-layer packaging | Cost – solvents can be expensive and costs more with more mixed materials, may require other infrastructure Output quality depends on input quality and process parameters – better with mono-material streams (PVC (#3), PS (#6), PET (#1), PP (#5)) and cannot improve degraded plastics | Financial incentives; R&D support Collection that supports mon-material streams |

Incorporating recycled content into new products

One of the conceptually simplest ideas to improve the effectiveness of recycling systems is the use of recycled plastics to make new product that can then be recycled. This prevents use of landfill, and release of further carbon from fossil-fuel sources. As people have become more conscious of the damage done by plastics in the environment, companies have begun to incorporate the use of recycled products as part of their branding.

The key issues that need to be addressed to increase incorporation of recycled content into new products are:

- Ensuring that use of recycled plastics in food packaging does not cause food safety risks (via chemicals or contaminants)

- The unstable recycled plastic market

- The drop in strength and appearance through cycles: though in theory certain plastics are infinitely recyclable, in practice materials will reach their end-of-life, particularly with mechanical recycling, and require disposal at some point

- Using lower quality, i.e. not 100% pure, recycling streams requires innovations in processing methods to account for the different properties and variations in the plastic raw material (e.g. chemical recycling technology).

Innovations and ideas to improve incorporation of recycled content into new products are outlined in the table below.

Ecostore made a line of bottles from 100% recycled ocean waste plastics. Photo credit: Ecostore.

Ideas to increase the use of recycled content in new products

| Technology | Who | Examples/early adopters | Strengths | Limitations for implementation | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boost demand through government procurement and targets | Government | New government procurement rules (rule 20) | Strengthens market for recycled plastics | Infrastructure for quality recycled plastics Difficulty identifying products that have recycled content | Create a resource that identifies local products with recycled content |

| Labelling to promote recycled content | Brands | ARL to include this in phase 2 (read the case study 'The Australasian Recycling Label') Ecolabel | Consumer appeal | Ecolabel doesn’t include single-use plastics | Implement ARL |

| Mandate use of recycled plastic | Government | California bill (stalled) UK (Wales and Scotland) – Taxing products with <30% recycled products and bringing in CDS | Strengthens market for recycled plastics Evens the playing field so early adopters not disadvantaged | Requires importing recycled resin with current limited infrastructure Slower to implement Need to factor in food safety issues which may require virgin layer | Could be achieved in product stewardship schemes for packaging Send signal to business of date when implemented for transition period Phase in targets with development of onshore processing and market creation |

| Implement targets | Government/ Industry | NZ Plastics Packaging Declaration and New Plastics Economy Global Commitment APCO and UK Plastics Pact targets of 30% average recycled content for packaging by 2025 | Simplicity | Hard to control imports Uptake may be limited unless mandated | International agreements Explore international product stewardship as part of trade agreements e.g. CPTPP |

| Industry working groups to establish market for recycled plastic | Industry | Post-consumer recycling of PP (#5) NEMO (new end market opportunities) US initiative Recycling Demand Champions (read the case study 'Incentivising use of recycled plastic') | Quick to implement Continue to signal strong demand for recycled material | When recycled resin has a higher price than virgin it may limit voluntary uptake | Establish a pact or industry working group to support issues of market pull through by connecting groups (could connect to existing pledges) |

| Blockchain/ big data | Industry/ Government | Enevo | Transforming waste management into a data driven and demand-based model Utilisation of predictive analytics, performance analysis, accuracy of measurement Transparency of the plastic waste value chain, enhances business model innovation | Fragmented regional collection policies Cost to public infrastructure | National plastic waste management system |

| Innovations to recycle ocean plastics | Business | Clothing, e.g. Girlfriend and Adidas Ecostore ocean plastics range Coca-Cola developed proof-of-concept bottle with 25% ocean plastics Formway designs chair | Potential for sustainability label to add consumer appeal | Market size Potential contamination issues may limit use in food and drinks packaging | Partner with international initiatives Assess risks of using these in food packaging and pending results, limit to certain applications if necessary |

Replace

Plastics are so widely used because they are cheap, light, durable and waterproof, and can be impermeable to air. This mixture of properties was not found in the natural materials available before the development of plastic and led to their rapid uptake by manufacturers and consumers. The major drawbacks of plastics are the toxic compounds that are sometimes added during their formulation, their persistence in the environment – an unintended consequence of their durability – and the fact they are sourced from fossil fuels.

While we can return to the use of pre-plastic era materials such as glass, paper, wood and steel, they have disadvantages. For example, glass is durable and air-tight, but heavy and manufacture has a high energy intensity; paper is light and cheap, but mostly not waterproof. Materials science offers the promise of new polymeric materials that can solve these problems, which are also fit for purpose and more sustainable.

The long-term goal is to develop and use a suite of new materials that are bio-based, biodegradable, sustainably produced and able to fulfil a wide range roles including packaging application. In the short-term, there are priority areas for innovation to replace particularly problematic materials. These include:

- Foils/laminates

- Synthetic fabrics that shed microfibres

- Difficult-to-recycle plastics used in packaging (PVC (#3), PS (#6) and various resins that fall into the ‘other’ category).

Any introduction of new plastics or alternative materials needs to be guided from a system perspective.[11] There are several particularly important considerations when introducing new materials to replace the problematic plastics we currently use:

- Is it safe? All new materials or new applications of existing materials need to have their safety profile tested. This is particularly true of new materials made from recycled plastic, as chemical additives may be carried into a new product depending on the quality or method of recycling (e.g. mechanical or chemical).

- Is this a better alternative for the environment? The environmental impacts from the whole life cycle of the product should be considered, including any reductions in preservation of the product, to assess how these differ and whether the new material is better than the plastic being replaced. Environmental impacts may be further reduced if the material can be reused multiple times before being recycled.

- What might the unintended consequences be? Lessons can be learned from the example of bisphenol-A (BPA) – an industrial chemical that is a common component of and additive to plastics and resins. Of roughly 30 chemicals that have been used to replace BPA, almost none are demonstrably safe.

- How does it fit into the current and future system of circular materials? We need to consider compatibilities with the current and future recycling infrastructure and practices to make sure that when new materials are introduced there are systems in place to keep these materials in circulation or recycled multiple times.

The types of new materials (including textiles) we should consider include:

- Bio-based plastics: The source material comes from biomass, decoupling the production of plastics from fossil fuels and supporting the transition to a circular economy. Provided the biomass is produced sustainably and the energy input (i.e. fossil-fuel input) involved in growing, fertilising, harvesting and processing the biomass is not greater than simply making plastic from crude oil, these may have reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Use of bio-based plastics is predicted to increase from around 4 million tonnes produced in 2016 to 6 million tonnes in 2021. Bioplastics currently comprise only 1% of total plastics production, so there is plenty of scope to increase the use of these plastics. As discussed in Section 1.2.4, ‘bio-based plastics’ and ‘biodegradable plastics’ mean different things and plastics can be either or both – the first relates to what it is made from and the other to how it breaks down.

- Biodegradable and compostable plastics: These allow for simple disposal of plastic items at their end-of-life with the resulting materials being put to use as compost or degrading in the environment. Compostable plastics require new processing methods to fully meet market needs and are typically more expensive than fossil fuel- based plastics. More companies have been using compostable plastics in recent years, but studies in Aotearoa New Zealand have highlighted a lack of infrastructure to manage compostable plastic waste. Considerable research is being undertaken internationally and in Aotearoa New Zealand to solve current issues with compostable plastics. The disposal of compostable plastics is complicated by the fact that some materials, notably most forms of PLA, need industrial high temperature composting facilities to fully degrade.

- Next-generation plastics: Less research is being done on wholly new materials to make plastics because of the challenges of manufacturing at sufficient scale and low enough price to replace existing plastics.

- Non-plastic alternatives: A whole range of new materials is being developed from a wide variety of sources to replace plastics. Many of these are developed from renewable sources.

As well as new materials, new manufacturing processes designed to complement their properties are being designed. For example, new innovations include additive manufacturing (e.g. 3D and 4D printing). Materials innovations are occurring worldwide in industry and academia, and through collaborations between the two, but uptake at larger scale is limited, particularly locally (read the case study ‘What’s stopping the uptake of new materials?’). In Aotearoa New Zealand, there are several research institutes that are able to collaborate with businesses to develop customisable solutions and progress our transition to a more bio-based circular economy for plastic use. For example, Scion has collaborated with Zespri to develop the Biospife (read the case study ‘Staying at the leading edge of global sustainability trends’), with EPL to develop a biodegradable wine net clip, and with Imagin Plastics to develop a 3D printer filament.

There is great potential for Aotearoa New Zealand’s research institutes and universities to carve out a niche for our plastics manufacturing industry in the bio-based and biodegradable plastics markets and to connect with international research efforts for new materials (e.g. the NSF Centre for Sustainable Polymers). Ensuring we keep up with international best practice is a particularly important consideration for our export industry. As a country that relies heavily on our export industry, it is imperative that Aotearoa New Zealand factors in the potential implications of international regulations relating to circular economy and sustainable packaging initiatives. An example of where innovation allowed a large exporter to meet the sustainability demands of the countries they export to is the biospife developed by Zespri (read the case study ‘Staying at the leading edge of global sustainability trends’).

In the table below we present opportunities and limitations of new alternatives to replace traditional plastics. We discuss how these may or may not play a role in Aotearoa New Zealand’s transition to a circular economy.

Material innovations and their potential application in Aotearoa New Zealand

| Material | Strengths | Limitations | Possible solutions | Examples/ongoing research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-PET (#1) A partially bio-based plastic | Fully recyclable Identical to fossil-PET (#1) so can be processed with it Existing infrastructure is sufficient | Currently relies on some fossil-based feedstock and doesn’t reduce environmental impacts compared to standard PET (#1) (read the case study 'Plastics – Is plant-based really greener?') Non-biodegradable if leaked into environment | R&D to make 100% bio-sourced – widely sought | Coca-Cola planning to make 100% bio-based PET (#1) bottles by 2020 |

| Bio-HDPE (#2) A bio-based plastic | Fully recyclable and can be reprocessed with standard HDPE (#2), so existing infrastructure is sufficient Ethylene, the raw material, is readily bio-sourced | Non-biodegradable if leaked into environment Cost is currently a barrier for companies | Develop onshore sourcing/ production Incentives for brands to use bio-based plastics | Ecostore use a bio-HDPE (#2) product |

| Bio-sourced polyester A bio-based plastic | Recyclable (in practice) | Lacking system to recycle clothing Most clothing imported, not manufactured in NZ | Retailers to demand bio-based options | |

| PLA A bio-based, compostable plastic | Circular potential because the compost produced can be used to grow plants to generate more PLA Physical properties similar to PET (#1) so could be a substitute for these applications | Severe incompatibility with PET (#1) recycling, but easily mistaken for PET (#1) – high potential to contaminate[12] Lack of technology in current sorting systems to recognise and remove PLA from PET (#1) stream Lack of available commercial composting infrastructure Currently no local manufacture In low oxygen environments, particularly landfill, degradation can produce methane Not currently mechanically recyclable in NZ Still persistent if leaked into environment | Sorting technology Build commercial composting facilities Build onshore manufacturing facility Use modern landfill or capture methane from degradation | NZ companies providing PLA packaging, e.g. Earthpac, Ecoware, Grounded Packaging Research to further develop underway at Otago[13] and Scion[14] |

| PHAs, including PHB A bio-based compostable or biodegradable plastic (depending on conditions) produced by microbial fermentation of a wide variety of feedstocks | Varied potential applications and properties (e.g. soft and rigid plastics) Circular potential because the compost produced can undergo microbial fermentation to produce more PHA Microbially degraded (not compost) can be degraded in the environment to water and CO2 – hence circular as plants can reuse Potential textile applications PHB properties similar to PP (#5) so could replace this PBAT evidence as fully biodegradable[15] PHB can be made from methane gas feedstock so additional climate change benefits – can use gas produced from landfills etc. Kaneka’s PHBH 90% marine biodegradable in 6 months Manufacture doesn’t require large, centralised facilities –suits onshore manufacture | Processing issues due to variability in feedstock Can be made from forestry waste so good economic opportunity for Aotearoa NZ If compostable plastics go into low oxygen environments, particularly into landfill, their degradation can produce methane. Not recyclable with current mechanical recycling infrastructure Cost prohibitive for brands | Proper testing facilities so only certified materials used locally (e.g. Scion) Use modern landfill to capture methane Use of waste streams as biomass to bring price down | Available now Bio-on develops numerous applications, including a cosmetic product line with Unilever Danimer is developing a variety of applications, including snack bag material for PepsiCo Research to improve underway at Scion and research to manufacture various types of PHA Methane-derived PHB developed by Mango Materials – currently produce textiles and caps in pilot plant |

| Seaweed-based packaging A non-plastic alternative | Can replace multi-layered plastic sachets Compostable | Competition for food source May contaminate plastic recycling streams Possible biosecurity issues | Use for niche applications | Evoware |

| Fungal protein-based materials A non-plastic alternative | Made from natural polymeric materials Can replace EPS, which is a problematic plastic | Possible allergenics Possible biosecurity issues when imported | Onshore manufacture | NZ Biopolymer Network partnership with Meadow Mushrooms to make mushroom packaging The US company Ecovative Design grows the structural component of fungi, mycelia, to replace plastics used in packaging The SCOBY (symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast bound in cellulose) that ferments tea into kombucha has been used a textile by US company Kombucha Couture |

| Cork A non-plastic alternative | Bio-based and biodegradable Anti-bacterial, water-resistant and strong | Scale | Lush has developed carbon-positive cork packaging to replace plastic | |

| Vitrimers A next-generation plastic | Recyclable/ remoldable version of thermosets Potential to replace lots of unrecyclable plastics that are discarded, especially thermosetting resins that are used in composite materials | Still in research and pilot phase | Further R&D Scale-up facilities | US company Mallinda developing new vitrimer composites |

| Recyclable thermosets A next-generation plastic | Drop-in solution to standard epoxy resins | Infrastructure to recycle | Develop this onshore | Connora makes these |

| Starch-derived materials A bio-based, compostable alternative to plastic | Compost produced can be used to grow plants to generate more starch to make their processing circular | Material properties e.g. poor water resistance limits use | Niche applications | Research at Scion Earthpac manufacture certified compostable starch-based products in NZ |

| Cellulose-based materials (e.g. bamboo, cellophane) A bio-based, compostable alternative to plastic | Made from natural materials | Material properties No current manufacture | Can purchase from international producers, e.g. Celluforce, Oji Japan, Stora Enso, Weidmann Fiber Technology Repurposing of current fibre mills (e.g. Oji in Japan) | Researchers at the University of Canterbury developing all-cellulose composites[16] Transparent wood cellulose: a fibrous cellulose (HefCel); and a plastic type cellulose (MMCC) developed but not yet on market Used for textiles substituting cotton and polyesters; coatings for paper and other product substitutes |

| Animal waste protein-based material A non-plastic alternative | Made from natural polymeric materials | In general these natural materials do not have the full range of desirable properties as plastics, particularly water and oxygen resistance, unless chemical additives are used, which may give the materials the same undesirable properties as plastic such as environmental toxicity | Niche applications Further R&D | Researchers from the University of Waikato have produced a plastic from meat rendering waste called Novastein that can be used as a biodegradable replacement for plastic in rigid items that do not require particular strength, such as seed trays and plant pots Researchers at the University of Canterbury and AgResearch developing these |

| Milk protein-based materials A non-plastic alternative | Made from natural polymeric materials | Application likely to be limited to specific niche applications where their properties are sufficiently desirable | Based on old methods but can be further developed | |

| Novel natural polymers A non-plastic alternative | Made from natural polymeric materials | Application likely to be limited to specific niche applications where their properties are sufficiently desirable | NZ company Humblebee is working on developing a material produced by a species of bee to waterproof their nests. The material is resistant to temperature, acids and bases, and solvents but, as mimicking a natural material, is likely to be biodegradable. Work is ongoing to develop a manufacturing method | |

| New composites A next-generation plastic | Wide-ranging potential applications, e.g. chair seats, automotive parts, shoe heels, garden pieces, lamps, 3D printing materials Can couple new materials with range of plastics | Recyclability | Design for circular principles (e.g. for disassembly and repair) to keep in use | Research underway looking at using harakeke in with pre-consumer recycled PP (#5) to make a composite[17] Scion has developed Woodforce, natural wood fibres replacing glass fibre in plastic composites |