Glossary and appendices

Here we provide definitions of te reo Māori terms, technical terms and abbreviations used throughout the report. You can also find appendices to accompany the main report content.

Contents

- Some key technical terms and how we use them

- Te reo Māori terms

- Technical terms and abbreviations

- Appendices

- Appendix 1: EAFM principles and relevant Fisheries Act 1996 provisions

- Appendix 2: Climate change data

- Appendix 3: Estimates for newly trawled area

- Appendix 4: Land-based effects data

- Appendix 5: New Zealand fisheries legal instruments

- Appendix 6: Key regulators in Aotearoa New Zealand’s marine fisheries space

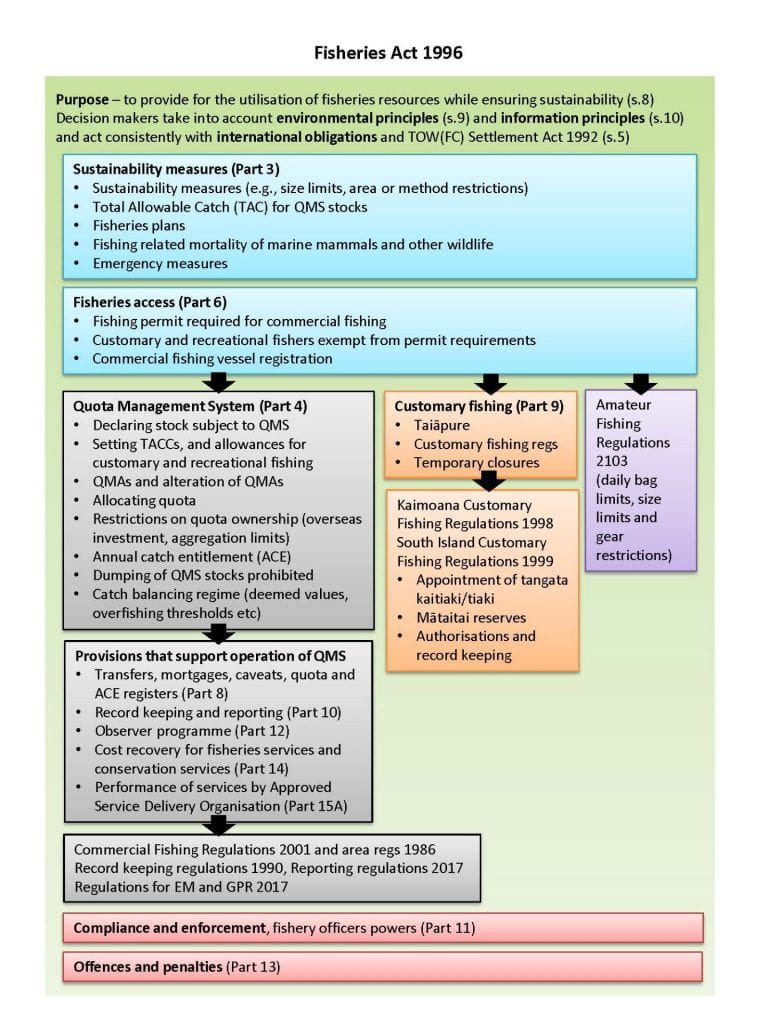

- Appendix 7: Fisheries Act 1996 schematic

- Appendix 8: Specific marine management acts

- Appendix 9: New Zealand international obligations

- Appendix 10: National fisheries plans management objectives

- Appendix 11: Some history surrounding an oceans strategy in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Appendix 12: Methods and applications of genetic technology in fisheries

- Appendix 13: Genetics in fisheries in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Appendix 14: Further examples of models

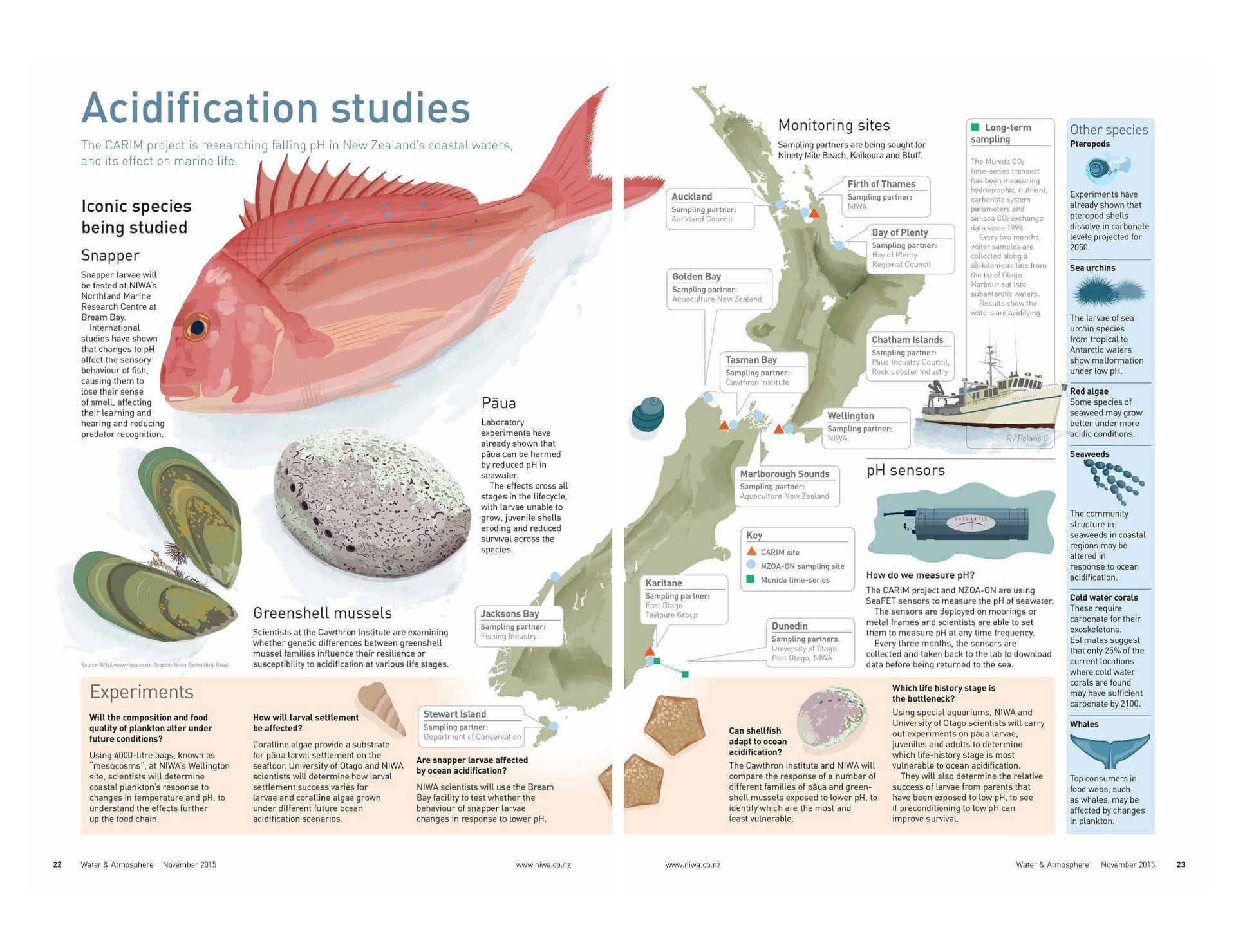

- Appendix 15: Ocean acidification studies underway

- Appendix 16: Plan for a New Zealand ocean observing system

- References and footnotes

Some key technical terms and how we use them

A report of this breadth is necessarily cross-disciplinary, incorporating input from a wide variety of people with different expertise, who may use terms in very specific (and sometimes rather different) ways. Here we lay out definitions of some key terms and how we use them in this report. A full glossary of technical terms and abbreviations with definitions can be found below. Approximate translations of all Māori words and phrases are also provided below.

This report is about commercial fishing: taking fish, aquatic life or seaweed in circumstances where a fishing permit is required as per section 89 of the Fisheries Act 1996. We use the term ‘commercial fisheries’ to refer to wild-caught marine life that is harvested to sell. We did not include seaweed in this report.

In this report, sustainability or sustainable use usually refers to sustainability as defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 – that is, (a) maintaining the potential of fisheries resources to meet the reasonably foreseeable needs of future generations, and (b) avoiding, remedying or mitigating any adverse effects of fishing on the aquatic environment. Sometimes, we use a narrower definition referring to the long-term maintenance of a single fish stock without considering the wider ecosystem impacts. At other times, we use a broader meaning of sustainability that encompasses ecological and social factors, including but not limited to biodiversity (genetic, species and ecosystem diversity), environmental and ecosystem impacts.

In this report, a stock or fish stock usually describes a management unit of a species as defined by Fisheries New Zealand (FNZ). A stock may be a discrete biological population, with little to no reproductive mixing with other stocks of the same species. In other cases, there may be migration or mixing between stocks.

Biodiversity refers to the variety of life. It pertains to the variety of different species present, the variability of ecosystems themselves, and diversity within species. Biodiversity is a critical part of ecosystem and planetary health but not the major focus of this report.

An ecosystem approach to fisheries management (EAFM) and ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) are different terms used widely in the literature. Both involve moving beyond single-species measures to incorporate wider ecosystem effects into management. We generally use EAFM, unless referring to specific literature which uses EBFM. They differ from ecosystem-based management (EBM) which refers to management of the ocean more broadly – not just fisheries.

Threatened species are those assessed according to the New Zealand Threat Classification System as facing imminent extinction because of their small total population size and/or rapid rate of population decline. This includes three sub-categories: ‘Nationally Critical’, ‘Nationally Endangered’ and ‘Nationally Vulnerable’. Protected species are defined under the Wildlife Act 1953. In the marine environment, all marine mammals, seabirds (except black-backed gulls), all sea turtles, some corals and some fish are protected species. A species may be protected but not threatened, or it may be both protected and threatened.

People from different disciplines use the term marine protected area (MPA) as an umbrella term for spatial areas in the marine environment where restrictions exist in order to conserve nature or maintain biodiversity values. There are a range of legal tools that offer differing levels of protection in the marine environment. Protected areas in the marine environment include marine reserves (as defined in the Marine Reserves Act 1971), benthic protection areas (BPAs), mātaitai and taiāpure reserves, and others. Different marine protection tools are discussed in detail here. The term MPA is often conflated with ‘marine reserve’ in everyday use, but is uses a wider definition in this report.

Te reo Māori terms

The translations are described based on the Māori Dictionary, and as they are used in this report. Other sources are noted in footnotes.

| Māori | English |

|---|---|

| hapū | kinship group, clan, subtribe |

| īnanga/īnaka | whitebait, juvenile freshwater fish of several species |

| iwi | tribe |

| kaimoana | seafood |

| kaitiaki | guardian |

| kaitiakitanga[1] | guardianship and conservation or protection; managing the environment based on a Māori worldview |

| kaumātua | elder, a person of status within the whānau |

| kaupapa Māori | Māori approach, ideology, topic or principles |

| ki uta ki tai[2] | from the mountains to the sea |

| kōhanga | nursery, birthplace |

| (te) korowai | cloak; the name of a group of marine guardians in Kaikōura |

| mahinga kai/mahika kai | food-gathering place, natural resources |

| mana | prestige, authority |

| mana whenua | power associated with possession and occupation of tribal land |

| manaakitanga | hospitality, kindness, generosity |

| mātaitai reserve[3] | recognise and provide for traditional fishing through local management. They allow customary and recreational fishing but usually don't allow commercial fishing; areas closed to commercial fishing that may also restrict recreational and customary fishing |

| mātauranga Māori | the body of knowledge originating from Māori ancestors, including the Māori worldview and perspectives, Māori creativity, and cultural practices |

| mauri | life force, vital essence |

| (te) moana | (the) ocean |

| rāhui | a temporary closure or prohibition; in the fisheries context, this generally involves restricting use of a fisheries area |

| rangatahi | younger generation, youth |

| rangatira | chief, supervisor |

| rangatiratanga | chieftainship, the right to exercise self-determination and sovereignty |

| rohe | district, region, area |

| rohe moana[4] | customary fishing area of tangata whenua |

| Tai Timu Tai Pari[5] | The tidal cycle, from low tide to high tide; Sea Change |

| taiāpure | local fisheries that are significant for food, spiritual, or cultural reasons; managed by local communities, which may have additional fishing rules |

| Tangaroa | the Māori god of the sea and fish; also the name of one of NIWA’s research vessels |

| tangata whenua | local people, people born of the whenua |

| taonga (species) | treasure; a native species of special cultural significance to Māori |

| tauiwi | non-Māori, foreigner, colonist |

| te hā o Tangaroa kia ora ai tāua | the breath of Tangaroa sustains us |

| Te Moutere o Motiti | Motiti Island |

| Te Ohu Kaimoana[6] | a statutory organisation dedicated to future advancement of Māori interests in the marine environment; this term is defined in the Māori Fisheries Act 2004 and the Fisheries Act 1996 |

| Te Wahipounamu | a World Heritage site incorporating four national parks including Fiordland National Park |

| tiaki | protect, conserve, look after |

| tikanga | correct procedure, custom, protocol, the customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context |

| tūpuna/tīpuna | ancestors |

| wāhi taonga[7] | places of sacred or extreme importance to Māori |

| wāhi tapu[8] | a place sacred to Māori in the traditional, spiritual, religious, ritual, or mythological sense |

| wairua | spirit |

| waka | canoe |

| whānau | family |

| whanaungatanga | relationship, kinship, sense of family connection forged through shared experiences |

Technical terms and abbreviations

Since this is a report on commercial fishing, where applicable, we have used the Fisheries New Zealand definition for technical terms and abbreviations in this glossary. We note that there are other definitions of many terms and discuss this for some key terms above.

| Term | Meaning | Also called |

|---|---|---|

| abundance | the amount of something as measured by number of individuals | |

| ACE | annual catch entitlement; an entitlement to harvest a quantity of fish, aquatic life, seaweed or other stock, taken in accordance with a fishing permit and any conditions and limitations imposed by or under the Fisheries Act 1996 | annual catch entitlement |

| AEBAR | aquatic environment and biodiversity annual review; a review produced each year by Fisheries New Zealand that presents scientific information on the effects of fishing on the environment, marine biodiversity, and aquatic environments | aquatic environment and biodiversity annual review |

| AFMA | Australian Fisheries Management Authority | |

| AI | artificial intelligence | |

| AIS | automatic ship identification system | |

| annual catch entitlement | an entitlement to harvest a quantity of fish, aquatic life, seaweed or other stock, taken in accordance with a fishing permit and any conditions and limitations imposed by or under the Fisheries Act 1996 | ACE |

| ANZBS | Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy | Te Mana o Te Taiao |

| AOS | acoustic-optical system | |

| aquaculture | the farming of fish or shellfish | |

| aquatic environment and biodiversity annual review | a review produced each year by Fisheries New Zealand that presents scientific information on the effects of fishing on the environment, marine biodiversity, and aquatic environments | AEBAR |

| B | biomass; the size of the stock in units of weight; often, biomass refers to only one part of the stock (e.g. spawning biomass, recruited biomass or vulnerable biomass, the latter two of which are essentially equivalent) | biomass |

| B0 | unfished biomass; the theoretical carrying capacity of the recruited or vulnerable biomass of a fish stock. In some cases, it refers to the average biomass of the stock in the years before fishing started more generally, it is the average over recent years of the biomass that theoretically would have occurred if the stock had never been fished B0 is often estimated from stock modelling and various percentages of it (e.g. 40% B0) are used as biological reference points to assess the relative status of a stock | original biomass, unfished biomass |

| BMSY | the average stock biomass that results from taking an average catch of maximum sustainable yield under various types of harvest strategies often expressed in terms of spawning biomass, but may also be expressed as recruited or vulnerable biomass BMSY is a common fisheries management target | |

| ballast | water taken in to a tank in the hull of vessels for stability | |

| bathymetry | the measurement of depth | |

| benthic | pertaining to the bottom of the ocean or the seafloor | |

| benthic protection area | any area established by the Fisheries (Benthic Protection Areas) Regulations 2007 as being a BPA | BPA |

| BERL | Business and Economic Research Ltd | |

| biodiversity | the variety and diversity of all life on land, in freshwater and in the sea, including the places where they live it pertains to the variety of different species present, the variability of ecosystems themselves and diversity within species | biological diversity |

| biofouling | the accumulation of microorganisms, plants, algae, or small animals on surfaces such as pipes or vessel hulls | |

| biogenic | produced by living organisms e.g. a coral reef is a biogenic structure | |

| biological diversity | the variety and diversity of all life on land, in freshwater and in the sea, including the places where they live it pertains to the variety of different species present, the variability of ecosystems themselves and diversity within species | biodiversity |

| biomass | the size of the stock in units of weight; often, biomass refers to only one part of the stock (e.g. spawning biomass, recruited biomass or vulnerable biomass, the latter two of which are essentially equivalent) | B |

| blue economy | a term that is sometimes used to capture a holistic approach to managing human use of the oceans, including biological, social and economic dimensions | ocean economy, marine economy |

| BOMEC | benthic-optimised marine environment classification | |

| BPA | any area established by the Fisheries (Benthic Protection Areas) Regulations 2007 as being a BPA | benthic protection area |

| BRUVS | baited remote underwater video station | |

| bryozoan | a family of aquatic invertebrate animals that form colonies | |

| bycatch | species not targeted by a fishery but caught incidentally during fishing operations | non-target species |

| calcareous | composed of calcium carbonate | |

| cartilaginous | made of cartilage, i.e. the skeletons of sharks | |

| CASAL | a fish stock assessment model | |

| catch per unit effort | the quantity of fish caught with one standard unit of fishing effort e.g. the number of fish taken per 1,000 hooks per day; or the weight of fish taken per hour of trawling CPUE is often assumed to be an abundance index a declining CPUE may mean that more effort e.g. metres of net set and/or length of soak time, is required to catch a given volume of fish; this in turn may indicate that a fish stock has declined (although other factors can also influence rates of CPUE, particularly the method used to catch the fish) | CPUE |

| catchability | catchability is the proportion of fish that are caught by a defined unit of fishing effort | |

| catchment | area of land in which rainfall drains towards a common watercourse, stream, river, lake or estuary | |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity | |

| CCSBT | Commission for Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna | |

| cetacean | aquatic mammals including dolphins, whales and porpoises | |

| chemoautotroph | organism that produces organic molecules by fixation of carbon dioxide, using energy derived from the oxidation of inorganic substances such as iron | |

| chimaera | a family of cartilaginous fish | ghost sharks |

| chondrichthyans | the family of cartilaginous fish including sharks, rays and ghost sharks | |

| CNN | convolutional neural network; a deep neural network inspired by the human vision system often used for image analysis | convolutional neural network |

| cod-end | the end of a trawl net which retains the catch and the part of the net where the most size selection takes place | |

| commercial fishing | taking fish, aquatic life, or seaweed in circumstances where a fishing permit is required; this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | |

| convolutional neural network | a deep neural network inspired by the human vision system often used for image analysis | CNN |

| CPR | continuous plankton recorder | |

| CPUE | the quantity of fish caught with one standard unit of fishing effort e.g. the number of fish taken per 1,000 hooks per day; or the weight of fish taken per hour of trawling CPUE is often assumed to be an abundance index a declining CPUE may mean that more effort e.g. metres of net set and/or length of soak time, is required to catch a given volume of fish; this in turn may indicate that a fish stock has declined (although other factors can also influence rates of CPUE, particularly the method used to catch the fish) | catch per unit effort |

| CRI | Crown Research Institute; crown-owned companies that carry out scientific research | |

| CSIRO | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation; Australia’s national science agency, similar to New Zealand’s CRIs | |

| customary fishing | the traditional rights confirmed by the Treaty of Waitangi and the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992, being the taking of fish, aquatic life, or seaweed or managing of fisheries resources, for a purpose authorised by Tangata Kaitiaki / Tiaki, to the extent that such purpose is consistent with Tikanga Māori and is neither commercial in any way nor for monetary gain or trade this term is defined in the Fisheries (Kaimoana Customary Fishing) Regulations 1998 | |

| demersal | pertaining to the seafloor and deep water column affected by the seafloor | |

| discards | any fish or other organisms that are landed but subsequently returned to the ocean | |

| DOC | Department of Conservation | |

| dredging | a fishing method where a steel net (a dredge) is towed along the seafloor by a vessel and scrapes up all the shellfish living there | |

| DTIS | deep towed imaging system | |

| EAFM | ecosystem approach to fisheries management; fisheries management that moves beyond single-species measures to incorporate wider ecosystem effects. Also called ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM); this differs from ecosystem-based management (EBM) which refers to management of the ocean more broadly – not just fisheries. | ecosystem approach to fisheries management, EBFM, ecosystem-based fisheries management |

| EBFM | ecosystem-based fisheries management; fisheries management that moves beyond single-species measures to incorporate wider ecosystem effects; also called ecosystem approach to fisheries management (EAFM); this differs from ecosystem-based management (EBM) which refers to management of the ocean more broadly – not just fisheries. | ecosystem-based fisheries management, EAFM, ecosystem approach to fisheries management |

| EBM | ecosystem-based management; using a holistic approach to management of the whole ocean taking into account the ecosystems | ecosystem-based management |

| ecosystem | an area where plants, animals, and other organisms, as well as weather and landscape, interact as a system | |

| ecosystem approach to fisheries management | EAFM; fisheries management that moves beyond single-species measures to incorporate wider ecosystem effects; also called ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM); this differs from ecosystem-based management (EBM) which refers to management of the ocean more broadly – not just fisheries | EAFM, EBFM, ecosystem-based fisheries management |

| ecosystem-based fisheries management | EBFM; fisheries management that moves beyond single-species measures to incorporate wider ecosystem effects, also called ecosystem approach to fisheries management (EAFM); this differs from ecosystem-based management (EBM) which refers to management of the ocean more broadly – not just fisheries | EBFM, ecosystem approach to fisheries management, EAFM |

| ecosystem-based management | EBM; using a holistic approach to management of the whole ocean taking into account the ecosystems | EBM |

| ecosystem thinking | a holistic perspective that moves beyond single-species measures to consider the whole ecosystem and its interconnections, including biodiversity | |

| echogram | the 2D output from an echosounder | |

| echosounder | a device that uses sound and echoes to detect organisms underwater | |

| eDNA | environmental DNA | |

| EEZ | Exclusive Economic Zone; a maritime zone over which the coastal state has sovereign rights over the exploration and use of marine resources usually, a state's EEZ extends to a distance of 200 nautical miles (nm) (approx. 370 km) out from its coast, except where resulting points would be closer to another country Aotearoa New Zealand has a 200 nm EEZ that was declared in 1978; the EEZ formally extends from the territorial sea at 12 nm (from the coastline) to 200 nm; this term is defined in the territorial sea and Exclusive Zone Act 1977 | Exclusive Economic Zone |

| EM | electronic monitoring | |

| EPA | Environment Protection Authority | |

| epigenetics | the study of changes in gene expression (active vs inactive genes) rather than the underlying DNA sequence | |

| ER | electronic reporting | |

| ERA | ecosystem risk assessment | |

| ESP3 | open-source software to process large hydro-acoustic datasets | |

| ESR | New Zealand’s Institute of Environmental Science and Research; a CRI | |

| Exclusive Economic Zone | Exclusive Economic Zone; a maritime zone over which the coastal state has sovereign rights over the exploration and use of marine resources usually, a state's EEZ extends to a distance of 200 nautical miles (nm) (approx. 370 km) out from its coast, except where resulting points would be closer to another country Aotearoa New Zealand has a 200 nm EEZ that was declared in 1978; the EEZ formally extends from the territorial sea at 12 nm (from the coastline) to 200 nm; this term is defined in the territorial sea and Exclusive Zone Act 1977 | EEZ |

| eutrophic | overly enriched with nutrients and/or minerals, resulting in excessive plant and algal growth (e.g. an algal bloom) and corresponding depletion in oxygen levels that may kill other organisms living in the water such as fish | |

| EwE | Ecopath with Ecoism; a type of ecosystem model | |

| FAD | fish aggregating device | |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization, part of the United Nations | |

| finfish | a bony, jawless or cartilaginous fish with fins, as opposed to shellfish | |

| FINZ | Fisheries Inshore New Zealand | |

| fish stock | in this report, a stock or fish stock usually describes a management unit of a species as defined by Fisheries New Zealand; a stock may be a discrete biological unit, with little to no reproductive mixing with other stocks of the same species in other cases, there may be migration or mixing between stocks | stock |

| Fisheries New Zealand | the government agency that regulates fishing in Aotearoa New Zealand, part of the Ministry for Primary Industries | FNZ |

| Fisheries Settlement 1992 | the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act became law in late 1992, and gave effect to the Deed of Settlement, signed in September 1992 this deed (1) settled Māori claims to commercial fishing; (2) clarified Māori rights to customary or non-commercial fishing; and (3) discharged the Crown’s obligations in respect of Māori commercial fishing interests under the Treaty of Waitangi | Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992; Māori Fisheries Settlement 1992 |

| Fishery Management Area | Fishery Management Area; the New Zealand 200 nautical mile EEZ is divided into 10 areas, each known as a Fishery Management Area FMAs are based on likely stock boundaries as well as administrative considerations; the standard FMAs are the basis of QMAs for most fish stocks; this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | FMA |

| FishServe | a subsidiary of Seafood New Zealand that provides administrative services to the Aotearoa New Zealand commercial fishing industry | |

| FMA | Fishery Management Area; the New Zealand 200 nm EEZ is divided into 10 areas, each known as a Fishery Management Area FMAs are based on likely stock boundaries as well as administrative considerations; the standard FMAs are the basis of QMAs for most fish stocks; this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | Fishery Management Area |

| FNZ | Fisheries New Zealand, the government agency that regulates fishing in Aotearoa New Zealand, part of the Ministry for Primary Industries | Fisheries New Zealand |

| Gazette | the New Zealand Gazette is the official government newspaper, published weekly; regulations are notified in the Gazette after they are made but before they come into force | |

| ghost gear | abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear | |

| ghost shark | a family of cartilaginous fish | chimaera |

| gillnet | vertical panels of netting held in place by regularly spaced floats and weights, catches sea life by entanglement | |

| GIS | geographical information system; an organised collection of computer hardware, software, geographic data, and personnel designed to efficiently capture, store, update, manipulate, analyze, and display all forms of geographically referenced information a GIS can combine relational databases with spatial interpretation and outputs often in form of maps | |

| GPR | geospatial position reporting | |

| GPS | global positioning system | |

| habitat | the place or environment that provides everything an organism needs to live and grow | |

| hard limit | biomass limit below which fisheries should be considered for closure | |

| HMS | highly migratory species | |

| HPSFM | habitats of particular significance to fisheries management | |

| hydroacoustic | the study and application of sound in water | |

| ikijime | a humane method of quickly killing fish originating in Japan, where a spike is quickly inserted just behind the fish’s eye | |

| individual transferable quota | a property right that represents the quota owners’ share of a fishery; ITQs can be bought or sold there are 100 million shares in each fish stock; the number of shares owned determines the amount of ACE generated each fishing year | ITQ |

| IOC | intergovernmental oceanographic commission | |

| ITQ | a property right that represents the quota owners’ share of a fishery; ITQs can be bought or sold there are 100 million shares in each fish stock; the number of shares owned determines the amount of ACE generated each fishing year | individual transferable quota |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature | |

| IUU | illegal, unreported and unregulated (of fishing) | |

| jigging | using a line with multiple baits, moving it up and down vertically to attract target species | |

| lacustrine | related to lakes | |

| landing | an amount of fish (or other marine life) harvested from the sea and brought onshore | |

| LAWA | Land Air Water Aotearoa | |

| LINZ | Land Information New Zealand | |

| longlining | using a very long fishing line with shorter lines and baited hooks every few feet | |

| machine learning | an application of AI where algorithms learn and improve from experience, rather than being explicitly programmed | |

| Māori Fisheries Settlement 1992 | the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act became law in late 1992, and gave effect to the Deed of Settlement, signed in September 1992 this deed (1) settled Māori claims to commercial fishing; (2) clarified Māori rights to customary or non-commercial fishing; and (3) discharged the Crown’s obligations in respect of Māori commercial fishing interests under the Treaty of Waitangi | Fisheries Settlement 1992; Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992 |

| marine economy | a term that is sometimes used to capture a holistic approach to managing human use of the oceans, including biological, social and economic dimensions | blue economy, ocean economy |

| marine protected area | an area of the marine environment especially dedicated to, or achieving, through adequate protection, the maintenance and/or recovery of biodiversity at the habitat and ecosystem level in a healthy functioning state | MPA |

| marine reserve | marine reserves are specified areas of the sea and foreshore that are managed to preserve them in their natural state for scientific study or other purposes marine reserves may be established in areas that contain underwater scenery, natural features or marine life, of such distinctive quality, or so typical, or beautiful, or unique, that their continued preservation is in the national interest; within a marine reserve, all marine life is protected and fishing and the removal or disturbance of any living or non-living marine resource is prohibited, except as necessary for permitted monitoring or research; this includes dredging, dumping or discharging any matter or building structures | |

| marine trophic index | a measure of the mean trophic level of fish caught | |

| maw | swim bladder | |

| maximum sustainable yield | MSY, the largest long-term average catch or yield that can be taken from a stock under prevailing ecological and environmental conditions; it is the maximum use that a renewable resource can sustain without impairing its renewability through natural growth and reproduction For most quota management stocks, the total allowable catch is set at a level that either moves the stock towards, or maintains the stock at or above a biomass level that can support the maximum sustainable yield (section 13 of the Fisheries Act 1996);this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | MSY |

| MBIE | Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment | |

| MEC | marine environment classification | |

| mesopelagic | inhabiting the intermediate depths of the sea around 200-1,000 m | |

| MfE | Ministry for the Environment | |

| MICE | models of intermediate complexity; a type of ecosystem model | |

| microchemical | analytical chemistry for studying small samples | |

| micronekton | group or organisms intermediate in size between zooplankton and nekton; consists mainly of crustaceans, small cephalopods and small fishes | |

| MPA | marine protected area; an area of the marine environment especially dedicated to, or achieving, through adequate protection, the maintenance and/or recovery of biodiversity at the habitat and ecosystem level in a healthy functioning state | marine protected area |

| MPI | Ministry for Primary Industries | |

| MSC | Marine Stewardship Council | |

| MSY | MSY, maximum sustainable yield, is the largest long-term average catch or yield that can be taken from a stock under prevailing ecological and environmental conditions; it is the maximum use that a renewable resource can sustain without impairing its renewability through natural growth and reproduction for most quota management stocks, the total allowable catch is set at a level that either moves the stock towards, or maintains the stock at or above a biomass level that can support the maximum sustainable yield (section 13 of the Fisheries Act 1996); this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | maximum sustainable yield |

| neural network | a type of machine learning system inspired by the structure of a human brain | |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing | |

| NIWA | National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research; a CRI that carries out a large amount of fisheries research under contract to MPI | |

| NOAA | National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (US) | |

| nominal stock | stocks that represent less than one percent of catch | |

| non-target species | species that are unintentionally caught or not routinely assessed for fisheries management | bycatch |

| nutraceutical | a substance that is a food or derived from food that provides medical or health benefits including the prevention and treatment of disease | |

| observer | a person placed onboard a fishing vessel to independently confirm catch and record a range of information such as bycatch species | |

| observer effect | observed trips do not represent unobserved trips as the presence of an observer changes fisher behaviour | |

| ocean economy | a term that is sometimes used to capture a holistic approach to managing human use of the oceans, including biological, social and economic dimensions | blue economy, marine economy |

| OIA | Official Information Act | |

| olfactory | related to the sense of smell | |

| oligotrophic | water bodies characterised by nutrient deficiency that can support few forms of life | |

| OOS/GOOS | Ocean Observing System; Global Ocean Observing System | |

| OPMCSA | Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor | |

| original biomass | B0; the theoretical carrying capacity of the recruited or vulnerable biomass of a fish stock; in some cases, it refers to the average biomass of the stock in the years before fishing started More generally, it is the average over recent years of the biomass that theoretically would have occurred if the stock had never been fished. B0 is often estimated from stock modelling and various percentages of it (e.g. 40% B0) are used as biological reference points to assess the relative status of a stock | B0, unfished biomass |

| otolith | part of the inner ear of fish important for balance and hearing; this grows from the centre out in a series of daily rings and seasonal bands or growth zones; otoliths can be used to identify the age of fish | |

| PCE | Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment | |

| pelagic | pertaining to the open ocean; neither close to the shore nor near to the seafloor | |

| phylodynamics | the study of population dynamics and evolutionary processes as it relates to the relationships between organisms of different species | |

| phytoplankton | microscopic marine algae | |

| pinger | an active sound emitter used to deter bycatch from net entanglement | |

| pinniped | family of semi-aquatic marine mammals including seals and sea lions | |

| plenary | Fisheries New Zealand holds fisheries assessment working groups throughout the year to discuss and review stock assessments; the working group meetings are open to the public, and include researchers, FNZ staff, commercial, customary, recreational and environmental stakeholders every year in May ‘plenary sessions’ are held to assess the fisheries managed within the QMS, as well as other important fisheries in the New Zealand EEZ, and to discuss various matters that pertain to fishery assessment a plenary report is then released by 31 May that summarises the conclusions and recommendations from the meetings of the Fishery Assessment Working Groups held during the previous months, as well as the Fishery Assessment Plenary session | |

| polyp | an individual belonging to the Cnidaria family which includes coral-forming organisms and sea anemones | |

| potting | a method of catching some marine species such as crayfish where a pot-like trap attached to a long rope is baited, dropped in the water and retrieved later; once entered, the target marine organism can’t escape | trapping |

| protected species | (a) any marine wildlife as defined in section 2 of the Wildlife Act 1953 that is absolutely protected under section 3 of that Act; (b) any marine mammal as defined in section 2(1) of the Marine Mammals Protection Act 1978; this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | |

| PVC | polyvinyl chloride; a type of plastic | |

| QMA | species within the QMS are managed by QMAs; QMAs are geographic areas within the EEZ the standard fishery management areas are the basis of quota management areas for most fish stocks | quota management area |

| QMS | the QMS controls the overall catches for virtually all the main fish stocks found within Aotearoa New Zealand’s 200 nautical mile EEZ | quota management system |

| quota | quota is a right which allows people to own a share of the 100 million shares available for a particular species in a defined area ownership of quota generates an annual catch entitlement to catch that stock; within the commercial catch limit, access is determined by ownership of ACE and the possession of a fishing permit | |

| quota management area | species within the QMS are managed by QMAs; QMAs are geographic areas within the EEZ the standard fishery management areas are the basis of quota management areas for most fish stocks | QMA |

| quota management system | the QMS controls the overall catches for virtually all the main fish stocks found within Aotearoa New Zealand’s 200 nautical mile EEZ | QMS |

| recruitment | the addition of new individuals to the fished component of a stock; this is determined by the size and age at which fish are first caught | |

| RFID | radio-frequency identification | |

| RFMO | regional fisheries management organisation | |

| rhodolith | calcareous nodules formed by marine algae found on the seafloor | |

| RMA | Resource Management Act 1991 | |

| ROV | remotely operated vehicle | |

| SDG | sustainable development goal | |

| seamount | a geological formation rising from the seafloor that does not reach the sea surface – essentially, an underwater mountain | |

| sediment | particles or clumps of soil, sand, clay, silt or other matter suspended in water | |

| SEFRA | spatially explicit fisheries risk assessment | |

| seine/seining | a fishing method using a net that hangs vertically and encircles a school of fish | |

| SFFF | sustainable food and fibre futures | |

| ShiPCC | sea-going high-performance computing cluster | |

| SIL | Seafood Innovations Ltd | |

| SLED | sea lion exclusion device | |

| SNP | single nucleotide polymorphism; a variation at a single site in a DNA sequence | |

| SNP-ChIP | a microarray to measure genetic variation | |

| soft limit | a biomass limit below which the requirement for a formal, time-constrained rebuilding plan is triggered | |

| spat | shellfish larvae attached to a surface | |

| spawning | the production or depositing of large quantities of eggs in water | |

| spawning biomass | the total weight of sexually mature fish in a stock that spawn in a given year | |

| SPM | spatial population model | |

| SSIF | strategic science investment fund | |

| SST | satellite surface temperature | |

| stock | in this report, a stock or fish stock usually describes a management unit of a species as defined by Fisheries New Zealand; a stock may be a discrete biological unit, with little to no reproductive mixing with other stocks of the same species in other cases, there may be migration or mixing between stocks | fish stock |

| stock assessment | the application of statistical and mathematical tools to relevant data in order to obtain a quantitative understanding of the status of the stock relative to defined benchmarks or reference points (e.g. BMSY) the results may include (1) an estimate of the current biomass relative to biomass targets; (2) an estimate of current and recent exploitation rates relative to optimum exploitation rates; (3) a determination of changes in the biomass of fish stocks in response to fishing; and/or (4) to the extent possible, a prediction of future trends in stock biomass stock assessments are based on (1) surveys; (2) knowledge of the habitat requirements, life history, and behaviour of the species; (3) likely environmental impacts on stocks; and (4) catch and effort statistics | |

| stock structure | (1) The geographical boundaries of the stocks assumed for assessment and management purposes (e.g. albacore tuna may be assumed to be comprised of two separate stocks in the North Pacific and South Pacific). (2) The boundaries that define self-contained populations in a genetic sense. (3) Known, inferred or assumed patterns of residence and migration for stocks that mix with one another | |

| sustainability / sustainable use | In this report, sustainability or sustainable use usually refers to sustainability as defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 – that is, (a) maintaining the potential of fisheries resources to meet the reasonably foreseeable needs of future generations, and (b) avoiding, remedying or mitigating any adverse effects of fishing on the aquatic environment. Sometimes, we use a narrower definition referring to the long-term maintenance of a single fish stock without considering the wider ecosystem impacts. At other times, we use a broader meaning of sustainability that encompasses ecological and social factors, including but not limited to biodiversity (genetic, species and ecosystem diversity), environmental and ecosystem impacts. | |

| TAC | total quantity of each fish stock that can be taken by commercial, customary Māori interests, recreational fishery interests and other sources of fishing-related mortality, to ensure sustainability of that fishery in a given period, usually a year; this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | total allowable catch |

| TACC | total quantity of each fish stock that the commercial fishing industry can catch in a given year; the TACC is a portion of the TAC that is set after allowances have been made for customary and recreational fishing, and for other sources of fishing-related mortality; this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | total allowable commercial catch |

| telson | the last segment in the abdomen or terminal appendage to the abdomen found in crustaceans such as rock lobsters | |

| tipping point | a point at which an ecosystem makes an abrupt shift between different states, driven by environmental change | |

| tori line | a type of bird-scaring fishing line with coloured streamers that is deployed behind a longline fishing vessel to deter seabirds from accessing baited hooks | |

| total allowable catch | total quantity of each fish stock that can be taken by commercial, customary Māori interests, recreational fishery interests and other sources of fishing-related mortality, to ensure sustainability of that fishery in a given period, usually a year; this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | TAC |

| total allowable commercial catch | total quantity of each fish stock that the commercial fishing industry can catch in a given year; the TACC is a portion of the TAC that is set after allowances have been made for customary and recreational fishing, and for other sources of fishing-related mortality; this term is defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 | TACC |

| trapping | a method of catching some marine species such as crayfish where a pot-like trap attached to a long rope is baited, dropped in the water and retrieved later; once entered, the target marine organism can’t escape | potting |

| trawling | a fishing method where a net is dragged through the water behind a vessel | |

| Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992 | the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act became law in late 1992, and gave effect to the Deed of Settlement, signed in September 1992 this deed (1) settled Māori claims to commercial fishing; (2) clarified Māori rights to customary or non-commercial fishing; and (3) discharged the Crown’s obligations in respect of Māori commercial fishing interests under the Treaty of Waitangi | Fisheries Settlement 1992; Māori Fisheries Settlement 1992 |

| trolling | a fishing method using a line, sometimes with multiple lures, and dragging it horizontally through the water to simulate prey movement | |

| trophic cascade | flow of changes in an ecosystem and relative abundance of prey species, triggered by the removal or addition of a top predator | |

| trophic level | the position an organism occupies in a food web | |

| turbidity | a measure of the murkiness of water due to the presence of suspended particles | |

| UAV | unmanned aerial vehicle | |

| UBA | underwater breathing apparatus | |

| UNCLOS | United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea | |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme | |

| unfished biomass | B0; the theoretical carrying capacity of the recruited or vulnerable biomass of a fish stock; in some cases, it refers to the average biomass of the stock in the years before fishing started More generally, it is the average over recent years of the biomass that theoretically would have occurred if the stock had never been fished. B0 is often estimated from stock modelling and various percentages of it (e.g. 40% B0) are used as biological reference points to assess the relative status of a stock | B0, original biomass |

| UNFSA | United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement | |

| UNGA | United Nations General Assembly | |

| UTF | underwater topographical feature | |

| VIAME | video and image analytics for marine environments | |

| VME | vulnerable marine ecosystem; a marine ecosystem is classified as 'vulnerable' based on the characteristics that it possesses, such as uniqueness or rarity; functional significance of the habitat; fragility; life-history traits of component species that make recovery difficult; and structural complexity’ examples are seamounts and deepwater coral forests. | vulnerable marine ecosystem |

| vulnerable marine ecosystem | vulnerable marine ecosystem; a marine ecosystem is classified as 'vulnerable' based on the characteristics that it possesses, such as uniqueness or rarity; functional significance of the habitat; fragility; life-history traits of component species that make recovery difficult; and structural complexity’ examples are seamounts and deepwater coral forests. | VME |

| WCPFC | Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission | |

| WGS | whole genome sequencing | |

| WWF | World Wildlife Fund | |

| xenophyphore | single-celled organisms that live on the seafloor, extracting minerals from their surroundings to construct an exoskeleton |

Appendices

Appendix 1: EAFM principles and relevant Fisheries Act 1996 provisions

Table taken directly from the Fathom report, ‘EAFM and the Fisheries Act 1996’ [9]

Usually we refer to sections of the Fisheries Act 1996 as section X. In this table, these are abbreviated to sX.

| Principles | Key Fisheries Act provisions |

|---|---|

| 1. Ensuring the sustainability of fish stocks | s11 sustainability measures; s13 total allowable catch (TAC); s14 and s14A alternative TACs. |

| 2. Rebuilding depleted stocks | s11 sustainability measures; s13 TAC |

| 3. Ecosystem integrity: safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystem structure and functioning | s8 purpose; s9 environmental principles; s11 sustainability measures. |

| 4. Taking account of species interactions | s9 environmental principles; s13 TAC; s15 fishing-related mortality of marine mammals and other wildlife. |

| 5. Minimising impacts on non-target species | s9 environmental principles; s11 sustainability measures; s15 fishing-related mortality of marine mammals and other wildlife; s72 dumping of fish prohibited. |

| 6. Protecting fisheries habitats | s9 environmental principles; s11 sustainability measures. |

| 7. Managing at appropriate spatial scale | s19 (QMS introduction); s11 sustainability measures; s11A fisheries plans; Part 9 taiāpure-local fisheries and customary fishing. |

| 8. Considering trans-boundary effects | s5 application of international obligations; s17A highly migratory species taken outside NZ fisheries waters; Part 6A high seas fishing; Schedule 1A (fish stocks agreement). |

| 9. Managing at appropriate temporal scale | s8 purpose; s9 environmental principles; s13 TAC; s11 sustainability measures; s11A fisheries plans. |

| 10. Adopting a precautionary approach | s5 application of international obligations; s8 purpose; s9 environmental principles; s10 information principles; s13 TAC. |

| 11. Using science and diverse forms of knowledge | s12 consultation; Part 10 record keeping and reporting; Part 12 observer programme. |

| 12. Broadening stakeholder participation | s12 consultation; various specific consultation provisions; s11A fisheries plans; various provisions enabling active stakeholder involvement; s5 application of Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992. |

| 13. Recognising and providing for Indigenous rights | s5 application of Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992; s12 consultation; s44 (settlement allocation); Part 9 taiāpure-local fisheries and customary fishing. |

| 14. Balancing utilisation and sustainability | s8 purpose. |

| 15. Taking account of social and economic factors | s8 purpose; s13 TAC; s14A alternative TAC; Part 9 taiāpure-local fisheries and customary fishing; s123 dispute resolution; Part 14 cost recovery. |

| 16. Taking account of environmental influences on fisheries | s11 sustainability measures; s13 TAC; s16 emergency measures. |

| 17. Encouraging integrated management | s6 application of RMA; s11 sustainability measures; s15 fishing-related mortality of marine mammals and other wildlife. |

Appendix 2: Climate change data

The table below highlights environmental areas of concern and summarises the Ministry for the Environment’s marine environmental reporting in these areas (taken from Our Marine Environment 2019). This is not a comprehensive summary of all environmental information available – it is to show what information is analysed and presented within the current environmental reporting framework.

Climate and oceans

| Indicator | Measurement | 2018/2019 summary |

|---|---|---|

| Sea-level rise | National mean trends in annual sea-level rise at four long-term monitoring sites (Auckland, Wellington, Lyttelton and Dunedin). | The rate of sea-level rise has increased (the average rate in the past 60 years was more than double the rate of the previous 60 years). |

| Ocean sea-surface temperature | Average temperature recorded by satellite since 1981. | The seas are warming – satellite data recorded an average increase of 0.2°C per decade since 1981. |

| Extreme wave events | Extreme wave events from 2008. | Frequency of extreme wave events is increasing to the east and south of New Zealand and decreasing on the North Island’s west coast and to the north of the Bay of Plenty. The short time period makes it too early to definitively separate this trend from longer-term climate cycles. |

| Ocean acidity | pH of New Zealand subantarctic surface waters along from the Munida Transect, from 1998. New dataset for coastal water pH for nine sites across NZ. | Long-term measurements of subantarctic waters off the Otago coast show an increase of 7.1% in ocean acidity in the past 20 years. More data is needed before role of climate change can be separated from other factors that may be affecting coastal water acidity. |

| Primary productivity | Abundance of phytoplankton (measured as chlorophyll-a) measured by satellite near the sea surface from 1997. | The abundance of phytoplankton has increased and decreased in different New Zealand waters. Changing oceanic productivity is specific to the location; an increase or decrease in one area may not have the same impacts as in another area. |

| Marine heatwaves | High sea-surface temperatures over significant area and for significant duration. | Marine heatwaves are increasing in frequency. A marine heatwave occurring in the Tasman Sea and south of the Chatham Rise in 2017/18 was unprecedented (based on data since 1981). |

Appendix 3: Estimates for newly trawled area

Tables reproduced from [10].

For the deepwater fish stocks, the number of cells contacted in a year, that had not been contacted in previous years, and the aggregate area and footprint within those cells. A base of 25,103 cells were contacted in 1990-94, and, for example, 1,316 cells were contacted in 1995 (but not in 1990-94), with an aggregate area of 1,201 km² and footprint of 1,022 km². The table shows the equivalent data for Tier 1 and Tier 2 fish stocks.

| Fishing year | No. new cells | Aggregate area (km²) | Footprint (km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. cells contacted in 1990-4 = 25,103 | |||

| 1995 | 1,316 | 1,201.5 | 1,022.3 |

| 1996 | 1,420 | 1,032.1 | 948.8 |

| 1997 | 1,185 | 916.0 | 868.5 |

| 1998 | 1,543 | 1,892.8 | 1,538.1 |

| 1999 | 1,388 | 1,360.6 | 1,172.7 |

| 2000 | 1,227 | 1,517.1 | 1,363.2 |

| 2001 | 737 | 715.7 | 614.1 |

| 2002 | 1,173 | 1,050.2 | 1,007.5 |

| 2003 | 633 | 703.5 | 629.7 |

| 2004 | 328 | 319.8 | 294.9 |

| 2005 | 557 | 587.0 | 519.9 |

| 2006 | 266 | 134.0 | 129.3 |

| 2007 | 251 | 153.4 | 143.7 |

| 2008 | 279 | 191.0 | 177.7 |

| 2009 | 220 | 99.7 | 96.6 |

| 2010 | 165 | 60.3 | 59.5 |

| 2011 | 167 | 59.1 | 58.7 |

| 2012 | 106 | 36.9 | 36.7 |

| 2013 | 74 | 35.6 | 35.0 |

| 2014 | 94 | 34.4 | 34.2 |

| 2015 | 178 | 171.8 | 157.7 |

| 2016 | 172 | 108.6 | 104.5 |

| 2017 | 100 | 60.8 | 59.4 |

| 2018 | 117 | 32.8 | 32.8 |

| 2019 | 73 | 89.9 | 85.7 |

For the inshore fish stocks, the number of cells contacted in a year, that had not been contacted in previous years, and the aggregate area and footprint within those cells. A base of 9,459 cells were contacted in 2008 (the fishing year that tow-level data were first collected for all inshore fisheries), and, for example, 1,497 cells were contacted in 2009 (but not in 2008), with an aggregate area of 819.3 km² and footprint of 775.9 km².

| Fishing year | No. new cells | Aggregate area (km²) | Footprint (km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. cells contacted in 2008 = 9,459 | |||

| 2009 | 1,497 | 819.3 | 775.9 |

| 2010 | 934 | 657.8 | 576.4 |

| 2011 | 771 | 304.1 | 296.9 |

| 2012 | 484 | 151.7 | 148.3 |

| 2013 | 384 | 145.4 | 142.4 |

| 2014 | 400 | 167.9 | 161.0 |

| 2015 | 316 | 133.0 | 130.2 |

| 2016 | 285 | 79.1 | 79.1 |

| 2017 | 275 | 80.6 | 80.5 |

| 2018 | 198 | 66.1 | 65.9 |

| 2019 | 196 | 63.5 | 62.3 |

Appendix 4: Land-based effects data

Fisheries New Zealand, as reported in the trends and indicators section of the Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Annual Review:

| Indicator | Measurement | 2018/2019 summary |

|---|---|---|

| Land-based effects on the coastal environment | ||

| A national view of the impacts of land‐based influences upon seafood production does not exist. | N/A | N/A |

The table below highlights environmental areas of concern and summarises the Ministry for the Environment’s marine environmental reporting in these areas. This is not a comprehensive summary of all environmental information available – it is to show what information is analysed and presented within the current environmental reporting framework.

Human land use and sediment impacts

| Indicator | Measurement | 2018/2019 summary |

|---|---|---|

| Sediment | Focus on sediment accumulation in estuaries. | Accumulation rates have increased. Intertidal sedimentation rates have generally increased and become highly variable since European settlement. |

| Biogenic habitats | Review of the state of key biogenic habitats using nationally available data. | Most have decreased (e.g. mussel beds, seagrass meadows). |

| Litter and contaminants | Beach litter density, monitoring of contaminants limited and inconsistent. | Have increased in the habitat and food webs, particularly plastic. |

| Water quality | Nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen), phytoplankton, oxygen, water clarity, and pH monitoring. | It is difficult to assess the overall state of coastal water quality. |

Appendix 5: New Zealand fisheries legal instruments

New Zealand fisheries legal instruments: Acts and regulations

| Instrument | Purpose | Lead |

|---|---|---|

| Fisheries Act 1996 & residual parts of Fisheries Act 1983 | Provides for the utilisation of fisheries resources while ensuring sustainability. Ensuring sustainability means:

| MPI |

| Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992 | Gives effect to settlement of claims relating to Māori commercial fishing rights:

| MPI |

| Māori Fisheries Act 2004 |

| MPI |

| Māori Commercial Aquaculture Claims Settlement Act 2004 |

| MPI |

| Aquaculture Reform (Repeals and Transitional Provisions) Act 2004 (provides only for transitional matters for aquaculture) |

| MPI |

| Driftnet Prohibition Act 1991 | Prohibits driftnet fishing activities and implements the Convention for the Prohibition of Fishing with Long Driftnets in the South Pacific. | MPI |

| Antarctic Marine Living Resources Act 1981 | Gives effect to the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources: No person shall in the Convention Area take any marine organism, whether alive or dead, without first obtaining a permit to do so. | MFAT |

| Wildlife Act 1953 | Consolidates and amends the law relating to the protection and control of wild animals and birds, the regulation of game shooting seasons, and the constitution and powers of acclimatisation societies. | DOC |

| Marine Mammals Protection Act 1978 | Makes provision for the protection, conservation, and management of marine mammals within New Zealand and within New Zealand fisheries waters. | DOC |

| Marine Reserves Act 1971 | Provides for the setting up and management of areas of the sea and foreshore as marine reserves for the purpose of preserving them in their natural state as the habitat of marine life for scientific study. | DOC |

| Conservation Act 1987 | Promotes the conservation of New Zealand’s natural and historic resources, and for that purpose to establish a Department of Conservation. | DOC |

| Resource Management Act 1991 | Restates and reforms the law relating to the use of land, air, and water. | MfE |

| Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects) Act 2012 |

| MfE |

| Environmental Reporting Act 2015 | Requires regular reports on New Zealand’s environment. | MfE |

| Biosecurity Act 1993 | An Act to restate and reform the law relating to the exclusion, eradication, and effective management of pests and unwanted organisms. | MPI |

| Crown Minerals Act 1991 | The purpose of this Act is to promote prospecting for, exploration for, and mining of Crown-owned minerals for the benefit of New Zealand. | MBIE |

| Maritime Transport Act 1994 | The functions of the Minister under this Act are:

| MoT |

| Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011 |

| MoJ |

| Fisheries (Reporting) Regulations 2017 | Regulations made under the Fisheries Act 1996. | MPI |

| Fisheries (Commercial Fishing) Regulations 2001 |

| MPI |

| Fisheries (Auckland and Kermadec Areas Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 | Places restrictions on types of fishing, fishing gear and permitted catch in areas around Auckland, Northland and the Kermadecs. | MPI |

| Fisheries (Challenger Area Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 | Places restrictions on types of fishing, fishing gear and permitted catch in the Challenger FMA. | MPI |

| Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 | Places restrictions on types of fishing, fishing gear and permitted catch in Southland and the subantarctic. | MPI |

| Fisheries (South-East Area Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 | Places restrictions on types of fishing, fishing gear and permitted catch in the South-East FMA. | MPI |

| Fisheries (Central Area Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 | Places restrictions on types of fishing, fishing gear and permitted catch in the Central FMA. | MPI |

| Fisheries (Infringement Offences) Regulations 2001 | Sets out infringement offences, fees and notices. | MPI |

| Fisheries (Foreign Fishing Vessel) Regulations 2001 | Outlines licensing, control and enforcement of foreign vessels operating in New Zealand’s EEZ. | MPI |

| Fisheries (Recordkeeping) Regulations 1990 | Sets out who must keep records within the fishing industry, what records must be kept, and how they must be kept. | MPI |

| Fisheries (South Island Customary Fishing) Regulations 1999 and Fisheries (Kaimoana Customary Fishing) Regulations 1998 | Tangata kaitiaki/tiaki (guardians) can be appointed for a specific rohe moana. Tangata kaitiaki/tiaki are proposed by tangata whenua and confirmed by the Minister. They authorise and manage customary activities within the rohe moana. The South Island Customary Fishing Regulations apply to the South Island and Stewart Island. The Kaimoana Customary Fishing Regulations apply to the North Island and Chatham Islands. | MPI |

| Ngā Rohe Moana o Ngā Hapū o Ngāti Porou Act 2019 |

| |

| Submarine Cables and Pipelines Protection Act 1996 | Protection of New Zealand’s undersea cables. | MoT |

| Fisheries (Amateur Fishing) Regulations 2013 |

| MPI |

Appendix 6: Key regulators in Aotearoa New Zealand’s marine fisheries space

Fisheries New Zealand (Ministry for Primary Industries)

Fisheries New Zealand is the key regulator tasked with guiding the sustainable use of fisheries resources to the greatest overall benefit to New Zealanders.

This focus includes the sustainability of New Zealand’s wild fish stocks, aquaculture, and the wider aquatic environment.

Key legislation Fisheries New Zealand administers includes:

- Fisheries Act 1996 and regulations

- Fisheries Act 1983 (residual parts)

- Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992

- Fisheries (Quota Operations Validation) Act 1997

- Māori Fisheries Act 2004

- Māori Commercial Aquaculture Claims Settlement Act 2004

- Aquaculture Reform (Repeals and Transitional Provisions) Act 2004

- Driftnet Prohibition Act 1991

- Antarctic Marine Living Resources Act 1981

Department of Conservation

The Department of Conservation is the key regulator for species protection and biodiversity in the marine space.

This includes marine reserves and parks, protection of protected or threatened species, and protection of biodiversity.

Key legislation the Department of Conservation administers includes:

Ministry for the Environment

The Ministry for the Environment is responsible for national environmental reporting, including the marine environment, and promoting the sustainable management of natural resources in our EEZ and continental shelf.

Key legislation the Ministry for the Environment administers includes:

Regional councils

Our 11 regional councils are responsible for managing the territorial sea (out to 12 nautical miles).

This includes land use and its impacts on the marine environment.

Regional councils are empowered in the marine space through the:

Other regulators

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade represents Aotearoa New Zealand in global discussions to ensure successful implementation of international agreements on ocean governance and fisheries management.

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment is responsible for health and safety in the marine environment. This includes managing permits and licences for oil, gas and minerals (via New Zealand Petroleum and Minerals).

Environmental Protection Authority is responsible for consenting, monitoring and enforcement under the EEZ Act.

Ministry of Transport is responsible for the Maritime Transport Act 1994.

Maritime New Zealand is responsible for managing maritime transport and its effects.

National Maritime Coordination Centre is responsible for managing Aotearoa New Zealand’s maritime surveillance. It is part of the New Zealand Customs Service.

Many other ministries have adjacent or supporting roles: Te Arawhiti, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Te Puni Kōkiri, Ministry for Culture and Heritage, New Zealand Defence Force, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Justice, Stats NZ, and Land Information New Zealand.

Appendix 7: Fisheries Act 1996 schematic

As provided by industry:

Appendix 8: Specific marine management acts

Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act 2000

- Integrates management of the natural, historic, and physical resources of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands, and catchments.

- Establishes the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park.

- Establishes objectives for the management of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands, and catchments.

- Recognises the historic, traditional, cultural, and spiritual relationship of the tangata whenua with the Hauraki Gulf and its islands.

- Establishes the Hauraki Gulf Forum.

Admin: Department of Conservation.

Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Management Act 2005

- Establishes the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Area and eight marine reserves in that area.

- Implements measures to assist in the preservation, protection, and sustainable management of the marine environment and biological diversity of the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Area.

- Establishes the Fiordland Marine Guardians to provide advice on fisheries management, biosecurity, sustainable management, and marine preservation and protection.

- Facilitates and promotes co-operation between the Guardians and management agencies, to assist in achieving the integrated management of the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Area.

- Acknowledges the importance of kaitiakitanga.

Admin: Ministry for the Environment.

Kaikōura (Te Tai ō Marokura) Marine Management Act 2014

- Recognises the local, national, and international importance of the coast and sea around Kaikōura (Te Tai ō Marokura) as a consequence of its unique coastal and marine environment and distinctive biological diversity and cultural heritage.

- Provides measures to assist the preservation, protection, and sustainable and integrated management of the coastal and marine environment and biological diversity of Te Tai ō Marokura.

- Acknowledges the importance of kaitiakitanga and local leadership.

- Establishes an advisory committee to provide advice regarding biosecurity, conservation, and fisheries matters within a marine management area.

- Establishes, within Te Tai ō Marokura:

- a marine reserve,

- a whale sanctuary,

- a New Zealand fur seal sanctuary, and

- various mātaitai reserves and taiāpure-local fisheries.

- Amends the Fisheries (Amateur Fishing) Regulations 2013 to provide specific regulation of amateur fishing in the marine management area.

Sugar Loaf Islands Marine Protected Area Act 1991

Ensures that the scenery, natural features, and ecosystems of the Protected Area that should be protected and conserved by reason of their distinctive quality, beauty, typicality, or uniqueness are conserved.

Admin: Department of Conservation.

Subantarctic Islands Marine Reserves Act 2014

Provides for the setting up and management of the Subantarctic Islands Marine Reserves, so as to conserve and protect its scenery, natural features and ecosystem.

Admin: Department of Conservation.

Appendix 9: New Zealand international obligations

| Instrument | Purpose | Admin |

|---|---|---|

| United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) | UNCLOS is a comprehensive regime of law and order in the world's oceans and seas establishing rules governing all uses of the oceans and their resources. | MFAT |

| United Nations Fish Stocks Agreements | Sets out principles for the conservation and management of straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks and establishes that such management must be based on the precautionary approach and the best available scientific information. | |

| United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | A collection of 17 global goals set by the 2015 UN General Assembly and adopted by all member states. Of particular relevance is SDG 14: Life below water – Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development. | |

| Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) | As an environmental treaty of the United Nations, CMS provides a global platform for the conservation and sustainable use of migratory animals and their habitats. Migratory species threatened with extinction are listed on Appendix I of the Convention. CMS Parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them. | |

| Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) | This intentional legal instrument is for the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilisation of genetic resources. Overall objective is to encourage actions, which will lead to a sustainable future. See also: Aichi Biodiversity Targets Aotearoa New Zealand reports every four years (see New Zealand’s Sixth National Report to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (2014-2018)). | |

| Aichi Biodiversity Targets | At the CBD meeting in November 2010, a Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 was agreed and published. This included the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, 20 targets that would move towards a world where “pressures on biodiversity are reduced, ecosystems are restored” and “biological resources are sustainably used”. The international community failed to achieve any of the targets by 2020, with progress made on only six of the 20 goals. | |

| South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation (SPRFMO) | An inter-governmental organisation that is committed to the long-term conservation and sustainable use of the fishery resources of the South Pacific Ocean and in so doing safeguarding the marine ecosystems in which the resources occur. The SPRFMO Convention applies to the high seas of the South Pacific. | |

| Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) | The aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. | DOC/MPI |

| International Whaling Commission (IWC) | In addition to regulation of whaling, today's IWC works to address a wide range of conservation issues including bycatch and entanglement, ocean noise, pollution and debris, collision between whales and ships, and sustainable whale watching. | MPI |

| Wellington Convention | Multilateral treaty to prohibit the use of fishing driftnets longer than 2.5 km in the South Pacific. See appendix 5: Driftnet Prohibition Act 1991. | |

| Noumea Convention | Aims to address the accelerating degradation of the world’s oceans and coastal areas through the sustainable management and use of marine and coastal environments. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation – Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries | Sets out principles and international standards of behavior for responsible practices with a view to ensuring the effective conservation, management and development of living aquatic resources, with due respect for the ecosystem and biodiversity. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation – International Plan of Action for Seabirds (IPOA-Seabirds) | The objective of the IPOA-Seabirds is to reduce the incidental catch of seabirds in longline fisheries where this occurs. See also New Zealand’s National Plan of Action – Seabirds 2020: Reducing the incidental catch of seabirds in fisheries. | MPI/DOC |

| Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) | The objective of this agreement is to achieve and maintain a favourable conservation status for albatrosses and petrels. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation – International Plan of Action for Sharks (IPOA-Sharks) | The objective of the IPOA-Sharks is to ensure the conservation and management of sharks and their long-term sustainable use. See also New Zealand’s National Plan of Action for the conservation and management of Sharks 2013 (was to be reviewed in 2018). | MPI |

| Convention for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) | Objective to ensure, through appropriate management, the conservation and optimum utilisation of southern bluefin tuna. | |

| Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPFC) | The objective of the Convention is to ensure, through effective management, the long-term conservation and sustainable use of highly migratory fish stocks in the western and central Pacific Ocean in accordance with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement. | |

| South Tasman Rise Orange Roughy Arrangement | Arrangement between Government of Australia and Government of New Zealand for the conservation and management of orange roughy on the South Tasman Rise. In New Zealand see the Fisheries (South Tasman Rise Orange Roughy Fishery) Regulations 2000. | |

| Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) | Applies to all Antarctic populations of finfish, molluscs, crustacean and seabirds found south of the Antarctic Convergence. | MFAT/MPI |

| Convention on the Conservation and Management of High Seas Fishery Resources in the South Pacific Ocean | The objective is to ensure, through effective management, the long-term conservation and sustainable use of highly migratory fish stocks in the south Pacific Ocean in accordance with the 1982 Convention and the Agreement. | |

| World Heritage Convention | The Convention sets out the duties of States Parties in identifying potential sites and their role in protecting and preserving them. By signing the Convention, each country pledges to conserve not only the World Heritage sites situated on its territory, but also to protect its national heritage. The States Parties are encouraged to integrate the protection of the cultural and natural heritage into regional planning programmes, set up staff and services at their sites, undertake scientific and technical conservation research and adopt measures which give this heritage a function in the day-to-day life of the community. |

Appendix 10: National fisheries plans management objectives

Management objectives of the National Fisheries Plan for Deepwater and Middle-depth Fisheries.[11]

| Management objectives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Use | 1 | Ensure the deepwater and middle-depth fisheries resources are managed so as to provide for the needs of future generations. |

| 2 | Ensure excellence in the management of New Zealand’s deepwater and middle-depth fisheries, so they are consistent with, or exceed, international best practice. | |

| 3 | Ensure effective management of deepwater and middle-depth fisheries is achieved through the availability of appropriate, accurate and robust information. | |

| 4 | Ensure deepwater and middle-depth fish stocks and key bycatch fish stocks are managed to an agreed harvest strategy or reference points. | |

| Environmental outcome | 5 | Ensure that maintenance of biological diversity of the aquatic environment and protection of habitats of particular significance for fisheries management are explicitly considered in management. |

| 6 | Manage deepwater and middle-depth fisheries to avoid, remedy or mitigate the adverse effects of these fisheries on associated or dependent and incidentally caught fish species. | |

| 7 | Manage deepwater and middle-depth fisheries to avoid, remedy or mitigate the adverse effects of these fisheries on the benthic habitat. | |

| 8 | Manage deepwater and middle-depth fisheries to avoid, remedy or mitigate the adverse effects of these fisheries on the long-term viability of endangered, threatened and protected species populations. | |

| Governance conditions | 9 | Ensure the management of New Zealand’s deepwater and middle-depth fisheries meets the Crown’s obligations to Māori. |

| 10 | Ensure there is consistency and certainty of management measures and processes in the deepwater and middle-depth fisheries. | |

| 11 | Ensure New Zealand’s deepwater and middle-depth fisheries are transparently managed. | |

Management objectives of the National Fisheries Plan for Highly Migratory Species (HMS).[12]

| Management objectives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Use | 1 | Support viable and profitable commercial tuna fisheries in New Zealand |

| 1.1 | Support initiatives to add value to HMS fisheries. | |

| 1.2 | Negotiate favourable country allocations for New Zealand fishers. | |

| 1.3 | Reduce administrative barriers to profitability in HMS fisheries. | |

| 1.4 | Recognise importance of access to fisheries resources in New Zealand and the South Pacific region, and identify potential threats and opportunities. | |

| 2 | Maintain and enhance world class game fisheries in New Zealand fisheries waters. | |

| 2.1 | Maintain and enhance recreational catch rates for HMS game fisheries. | |

| 3 | Māori interests (including customary, commercial, recreational, and environmental) are enhanced. | |

| 3.1 | Take into account the views of relevant iwi and hapū in management of HMS. | |

| 3.2 | Ensure abundant HMS for customary use. | |

| Environmental | 4 | Maintain sustainable HMS fisheries within environmental standards. |

| 4.1 | Encourage management of HMS at specified target reference points. | |

| 4.2 | Support the objectives of the National Plan of Action for Sharks. | |

| 4.3 | Promote sustainable management of HMS fisheries through RFMOs. | |

| 5 | Implement an ecosystem approach to fisheries management, taking into account associated and dependent species. | |

| 5.1 | Recognise value of HMS and their ecosystems, including predators, prey, and protected species. | |

| 5.2 | Improve the quality of information available on the capture of protected species. | |

| 5.3 | Avoid, remedy, or mitigate the adverse effects of fishing on associated and dependent species (including protected species), using a risk assessment approach. | |

| 5.4 | Support the objectives of the National Plan of Action for Seabirds. | |